In 1851, Great Britain stood at the very pinnacle of industrial and cultural leadership of the world.

But running in parallel was an undercurrent of class inequality, a fear of foreigners, and a contempt for internationalism.

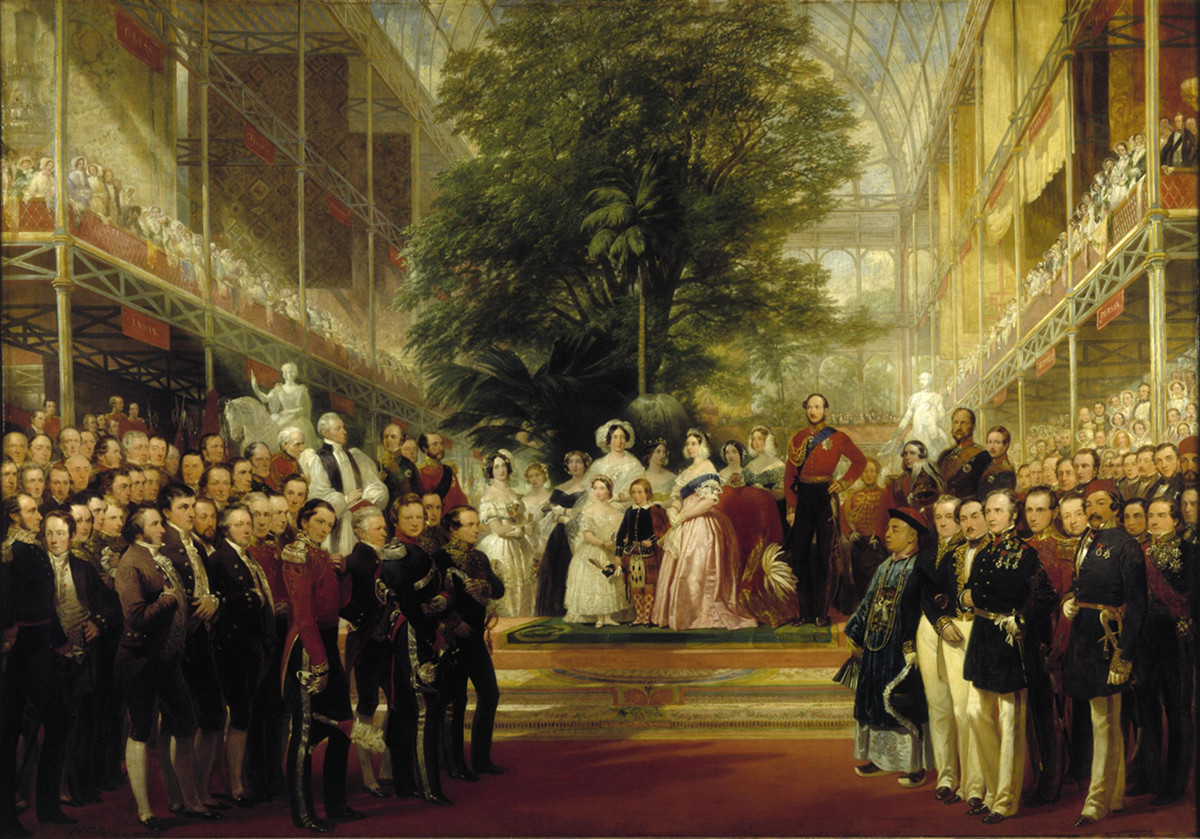

Against this backdrop, Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert organized the first world’s fair as a means to unite nations and encourage economic growth through international trade.

The first of many to come, the Great Exhibition was the symbol of Victorian progress and modernization.

Here are 10 fascinating facts about the Great Exhibition of 1851.

1. The Great Exhibition was a showcase for British pride

Although the Great Exhibition was a platform for countries from around the world to display their own achievements, Britain’s primary concern was to promote its own superiority.

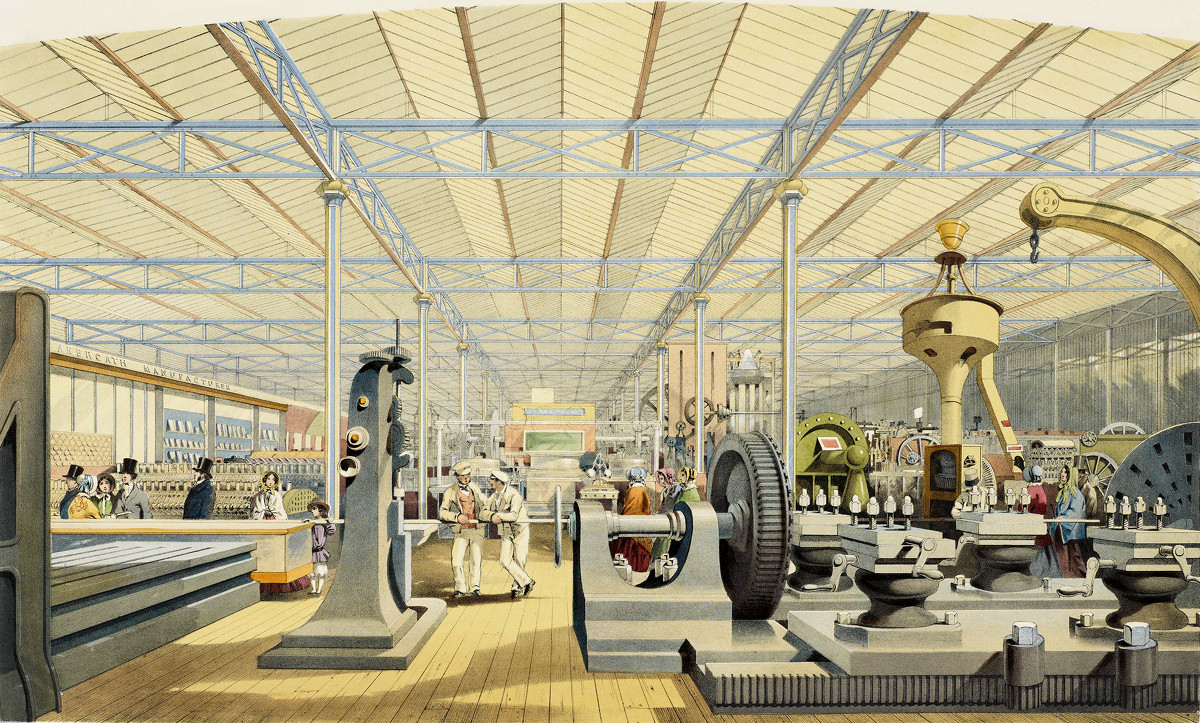

British exhibits held the lead in almost every field where strength, durability, utility and quality were concerned, whether in iron and steel, machinery, or textiles.

It was thought foreign visitors would look positively upon British accomplishments, customs, and institutions—learning more in the six months during the exhibition than the prior thirty-six years since the fall of Napoleon.

Great Britain also wanted to instill optimism and the hope for a better future.

Following two difficult decades of political and social upheaval in Europe, Great Britain hoped to convey that technology—particularly its own—was the key to a better future.

Despite being an advocate for internationalism, Prince Albert’s main objective was predominantly a national one—for Great Britain to make clear to the world its role as industrial leader.

Even so, some saw the rise of a new industrial power—one that would threaten Britain’s dominance in years to come.

With the industrial revolution well underway in the United States, the Great Exhibition was an opportunity for the former British colony to show its machines, products, and agricultural wealth on the world stage.

Unavoidably compared to Great Britain, many looked favorably on the United States’ offerings.

2. The Great Exhibition was a symbol of the Victorian Age

From the 1850’s onward, the term “Victorianism” became popular for describing the strength, bullish superiority, and pride of an ever-improving Britain.

Colonial raw materials and British art were displayed in the most prestigious parts of the exhibition.

Reflecting it’s important as the jewel in the crown of the British Empire, a disproportionately large area was allocated to India.

Opulently appointed, the India exhibits focused on the trappings of empire rather than technological achievements.

Technology and moving machinery proved popular, as did working exhibits like the entire process of cotton production from spinning to finished cloth.

Drawing attention from the curious-minded were scientific instruments, the like of which most people had never seen before, including electric telegraphs, microscopes, air pumps and barometers, as well as musical, horological, and surgical instruments.

Queen Victoria previewed the exhibition the day before the official opening and wrote in her journal “We saw beautiful china from Minton’s factory and beautiful designs”.

The combination of glazed and decorated bone china with unglazed Parian figures was praised by the Great Exhibition jury for its ‘original design, high degree of beauty and harmony of effect’.

Queen Victoria purchased a 116 piece ‘Victoria pierced’ dessert service in bleu celeste at the Great Exhibition.

She was overwhelmed by the spectacular service with allegorical figure supports modelled by Pierre-Emile Jeannest.

She purchased the service as a gift for the Empress of Prussia but gave permission for it to remain on display for the duration of the exhibition.

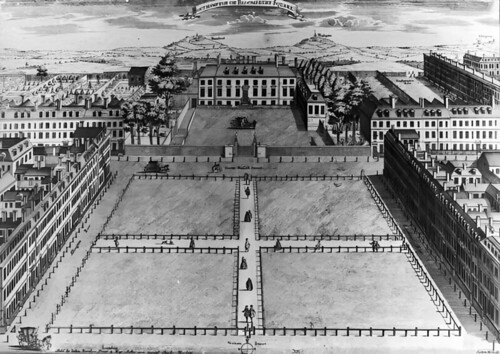

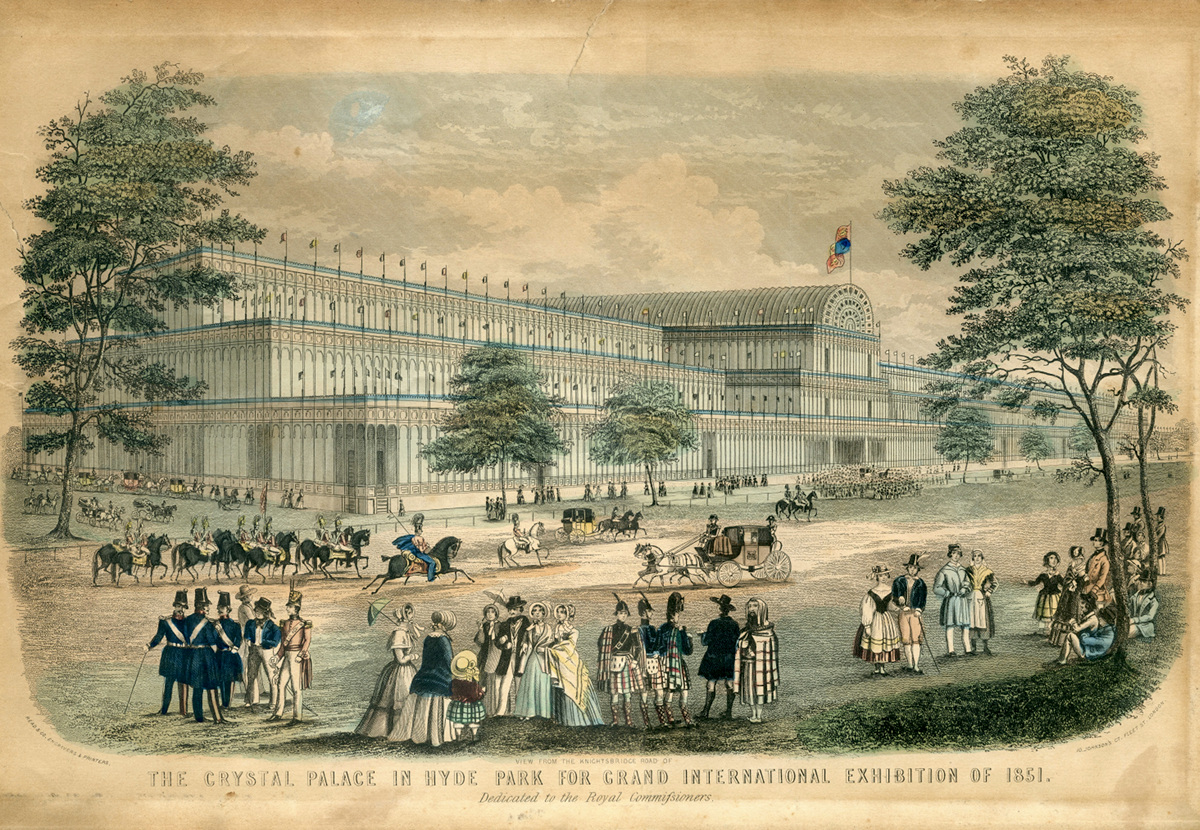

3. The Crystal Palace was purpose-built to house the Great Exhibition

Drawing on his experience building greenhouses for the Duke of Devonshire, architect Joseph Paxton designed the largest greenhouse in the world—so spacious was its interior that it fully enclosed some of Hyde Park’s own trees.

The Crystal Palace was an enormous success, considered an architectural marvel, but also an engineering triumph that reflected the importance of the Exhibition itself.

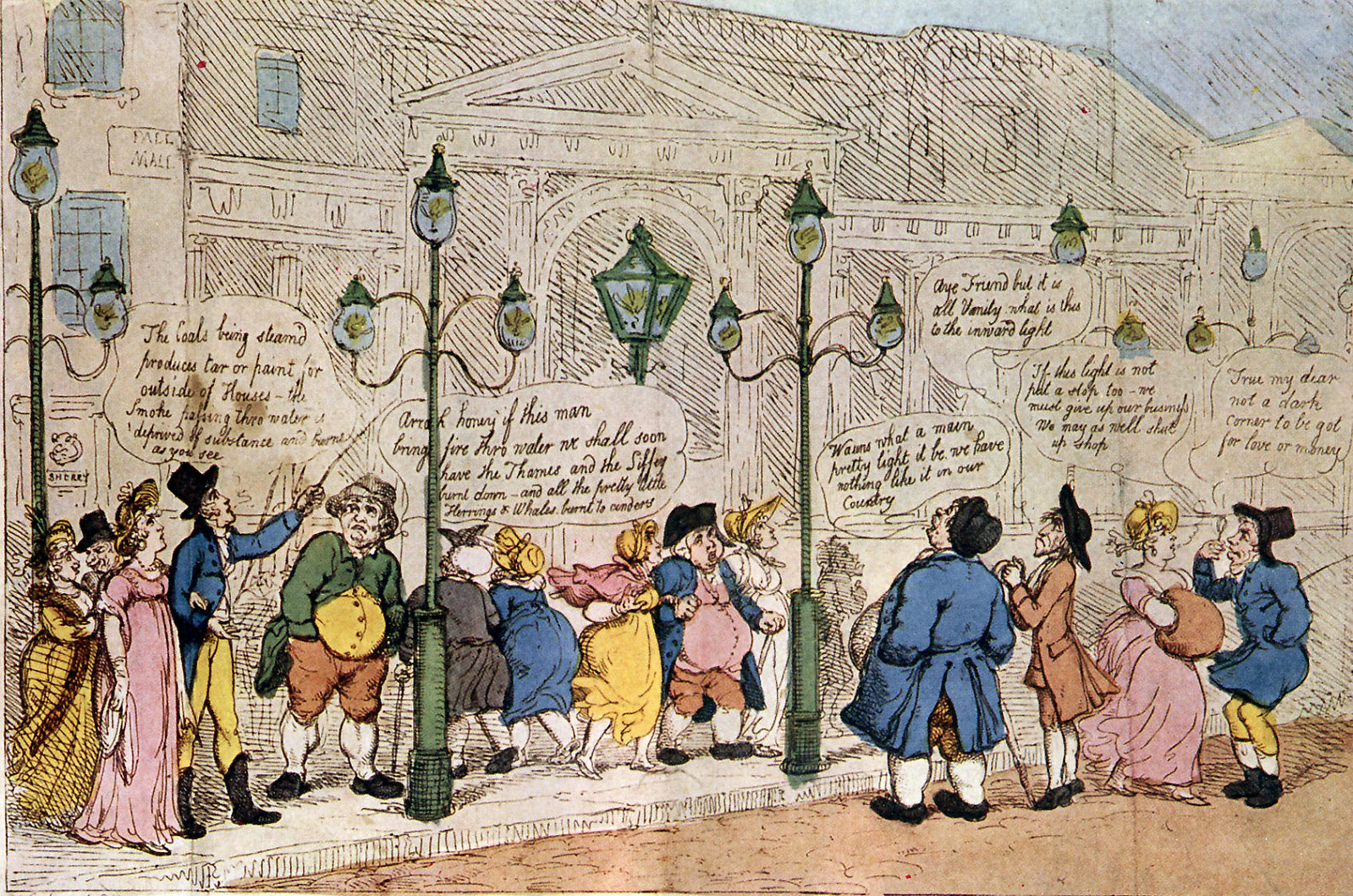

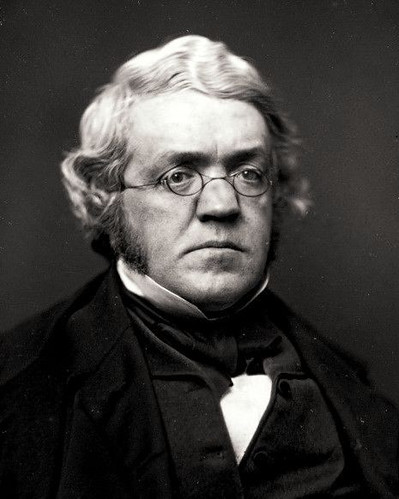

In the lead-up to the momentous Great Exhibition of 1851, William Makepeace Thackeray’s “May-Day Ode” appeared in The Times, its verses echoing through London’s streets like a triumphant fanfare. Published just one day prior to the opening ceremony, the poem served as more than just an ode to architectural innovation and colonial might.

As though ’twere by a wizard’s rod

As blazing arch of lucid glass

Leaps like a fountain from the grass

To meet the sun.

Thackeray’s lyrical brushstrokes painted the Crystal Palace not just as a testament to human ingenuity, but as a sacred space touched by the divine, bathed in the ethereal light of God’s grace. This literary offering stood as a potent symbol of Britain’s ambition, showcasing not only its industrial prowess and imperial reach, but also its enduring cultural and artistic influence. Open entire poem in a popup window: May-Day Ode

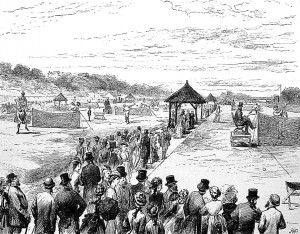

4. Six Million People visited 13,000 exhibits

Lasting six months, the average daily attendance at the exhibition was 42,831, with a peak attendance of 109,915 on 7 October.

One third of the entire population of Britain visited the Great Exhibition.

Whilst the western half of the building was occupied with exhibits by Great Britain and her colonies and dependencies, the eastern half was filled with foreign exhibits, with their names inscribed on banners suspended over the various divisions.

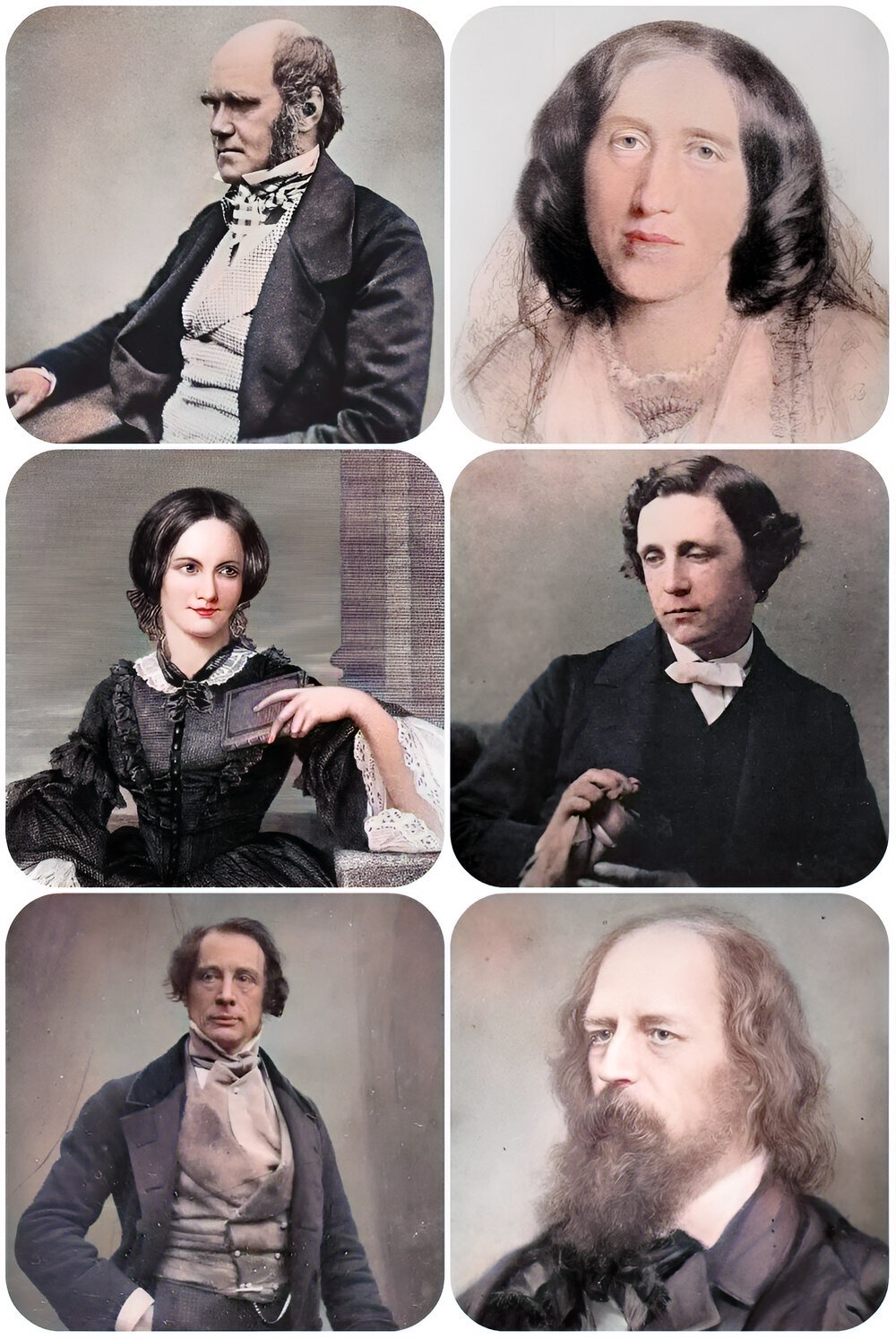

5. Numerous Victorian A-list celebrities visited the Great Exhibition

Attending the Great Exhibition were many notable celebrities of the time, including Charles Darwin, Samuel Colt, members of the Orléanist Royal Family and the writers Charlotte Brontë, Charles Dickens, Lewis Carroll, George Eliot and Alfred Tennyson.

Charlotte Brontë described her visit:

Yesterday I went for the second time to the Crystal Palace. We remained in it about three hours, and I must say I was more struck with it on this occasion than at my first visit. It is a wonderful place …

Read more …

… vast, strange, new and impossible to describe. Its grandeur does not consist in one thing, but in the unique assemblage of all things. Whatever human industry has created you find there, from the great compartments filled with railway engines and boilers, with mill machinery in full work, with splendid carriages of all kinds, with harness of every description, to the glass-covered and velvet-spread stands loaded with the most gorgeous work of the goldsmith and silversmith, and the carefully guarded caskets full of real diamonds and pearls worth hundreds of thousands of pounds. It may be called a bazaar or a fair, but it is such a bazaar or fair as Eastern genii might have created. It seems as if only magic could have gathered this mass of wealth from all the ends of the earth – as if none but supernatural hands could have arranged it this, with such a blaze and contrast of colours and marvellous power of effect. The multitude filling the great aisles seems ruled and subdued by some invisible influence. Amongst the thirty thousand souls that peopled it the day I was there not one loud noise was to be heard, not one irregular movement seen; the living tide rolls on quietly, with a deep hum like the sea heard from the distance.

6. The Great Exhibition broke through class barriers

Ever present in Victorian society was the nagging guilt that this age of individualism, capitalism, and overwhelming self-confidence could not be embraced by all.

Crushing poverty ran concurrent with enormous wealth.

But Prince Albert was not oblivious to the plight of the poor and was determined to make the Great Exhibition accessible to all.

Ticket prices came down dramatically as the exhibition progressed—in today’s equivalent, prices varied from £311 for a season ticket to about £5 for one day.

Thus even the working classes could afford to attend —four and half million of the cheapest day tickets were sold.

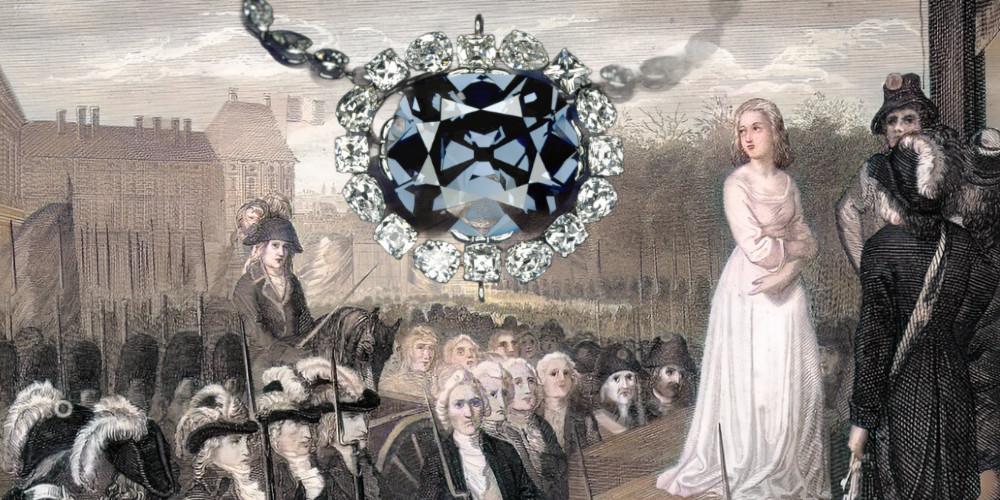

7. The world’s largest diamond had its own exhibit

The Koh-i-Noor, meaning the “Mountain of Light,” was the world’s largest known diamond in 1851.

One of the most popular attractions of the India exhibit, it was acquired in 1850 as part of the Lahore Treaty.

Dazzling and bewildering, the prismatically separated light of the Koh-i-Noor diamond was a metaphor for the Crystal Palace as a whole.

Originally thought to weigh as much as 793 carats, the earliest recorded weight was 186 carats, from which Prince Albert ordered it cut down to 105.6 carats so as to give the much brighter, oval-cut appearance preferred by Victorians—and fit for his Queen.

Today, the Koh-i-Noor diamond is set into The Queen Mother’s Crown and housed in the Tower of London.

8. The Great Exhibition was a great success, but was not without controversy

Just as today, there were naysayers who thought the Great Exhibition would be a flop.

Some people feared that in the face of grinding poverty, the building would be gutted by a revolutionary mob.

But the Great Exhibition of 1851 demonstrated the wisdom of internationalism at a time of widespread isolationism in Europe.

Its success inspired Napoleon III to open the second World’s Fair in Paris in 1855 and to hold some of the world’s grandest, including the Exposition Universelle 1889, for which the Eiffel Tower was built as a grand entrance.

By the time of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, attitudes had progressed even further by focusing not on nationalistic prowess, but on the history of the world and its peoples.

9. The profits funded three of London’s most loved museums

Built in the area to the south of the exhibition and nicknamed ‘Albertopolis’, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum and the Natural History Museum were all founded using the surplus profit from the Great Exhibition which amounted to a sum equal to £18 million in today’s money.

Even with the cost of these beautiful buildings, there was enough money left over to set up a trust for grants and scholarships for industrial research that continues to this day.

10. The Crystal Palace was destroyed by fire in 1936

After the Great Exhibition had come to a close, plans were drawn up to move the entire Crystal Palace structure to a new location in the suburbs of south-east London.

In 1852, the building went into private ownership and was moved to Sydenham, Kent.

Completely dismantled and re-built in the new Beaux-arts style, the greatly enlarged Crystal Palace was opened by Queen Victoria in 1854.

Costing six times as much to move as the original palace had cost to build, it became an extravagant money pit and the owners quickly fell into debt.

Unlike the unmitigated success of the Great Exhibition, the new Crystal Palace was plagued with financial woes.

Although Sunday was the only free day for the working classes, religious observance prevented the palace from opening.

Even when the palace did start to open on Sundays, people had largely lost interest and attendance was low.

Falling into a state of disrepair, and despite a restoration project by Sir Henry Buckland in the 1920s, tragedy struck on 30 November, 1936.

100,000 people came to watch the blaze, as 89 fire engines and over 400 firemen fought valiantly through the night.

One of the onlookers was Winston Churchill, who said, “this is the end of an age”.