Victoria is a British drama television series created by Daisy Goodwin and starring Jenna Coleman and Rufus Sewell.

There are many fascinating history lessons contained within the PBS Masterpiece series.

Here are 10 of our favorites.

1. Victoria’s dog “Dash”

Thought to have been Victoria’s closest childhood companion, Dash was a Cavalier King Charles spaniel initially given to her mother, the Duchess of Kent, by Sir John Conroy, the head of the Duchess’s household.

So close were Victoria and Dash that on one occasion when she went sailing on a yacht, Dash couldn’t bear being apart from her and jumped into the sea to swim after her.

Writing in her diary of Dash, she would shower him with words of affection: “dear sweet little Dash” and “dear Dashy”.

When Dash died, a marble effigy over the grave in Windsor Home Park read:

The favourite spaniel of Her Majesty Queen Victoria

In his 10th year

His attachment was without selfishness

His playfulness without malice

His fidelity without deceit

READER

If you would be beloved and die regretted

Profit by the example of DASH

2. The Kensington System

Raised largely isolated from other children under what was known as the “Kensington System”, Victoria had few if any childhood friends.

Devised by her mother and Conroy to render Victoria weak and dependent on their guidance, it comprised an elaborate set of rules and protocols.

Victoria’s every move was monitored and recorded.

Her mother and Conroy decided who she could and couldn’t see and trips outside the palace grounds were few and far between.

At some point, possibly from when she knew she would be Queen one day, Victoria’s courage grew and she resisted constant threats and intimidation to try to force her into appointing Conroy as her personal secretary and treasurer.

3. Sir John Conroy (1786 – 1854)

Serving as comptroller to the Duchess of Kent and her young daughter, Princess Victoria, Conroy was originally an equerry to Victoria’s father, Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn.

Thanks to the oppressive Kensington System, Victoria hated Conroy and had her revenge by expelling him from the royal household when she ascended to the throne.

Remaining in the Duchess’s service for a number of years, his attempts to discredit Victoria and plot to have her mother appointed as regent were unsuccessful.

Rumours circulated that the Duchess and Conroy were lovers. According to an account by the Duke of Wellington, the 10-year-old Victoria had reportedly caught Conroy and her mother engaged in “some familiarities”.

By 1842, Conroy retired to his Berkshire estate with a pension but died 12 years later, heavily in debt.

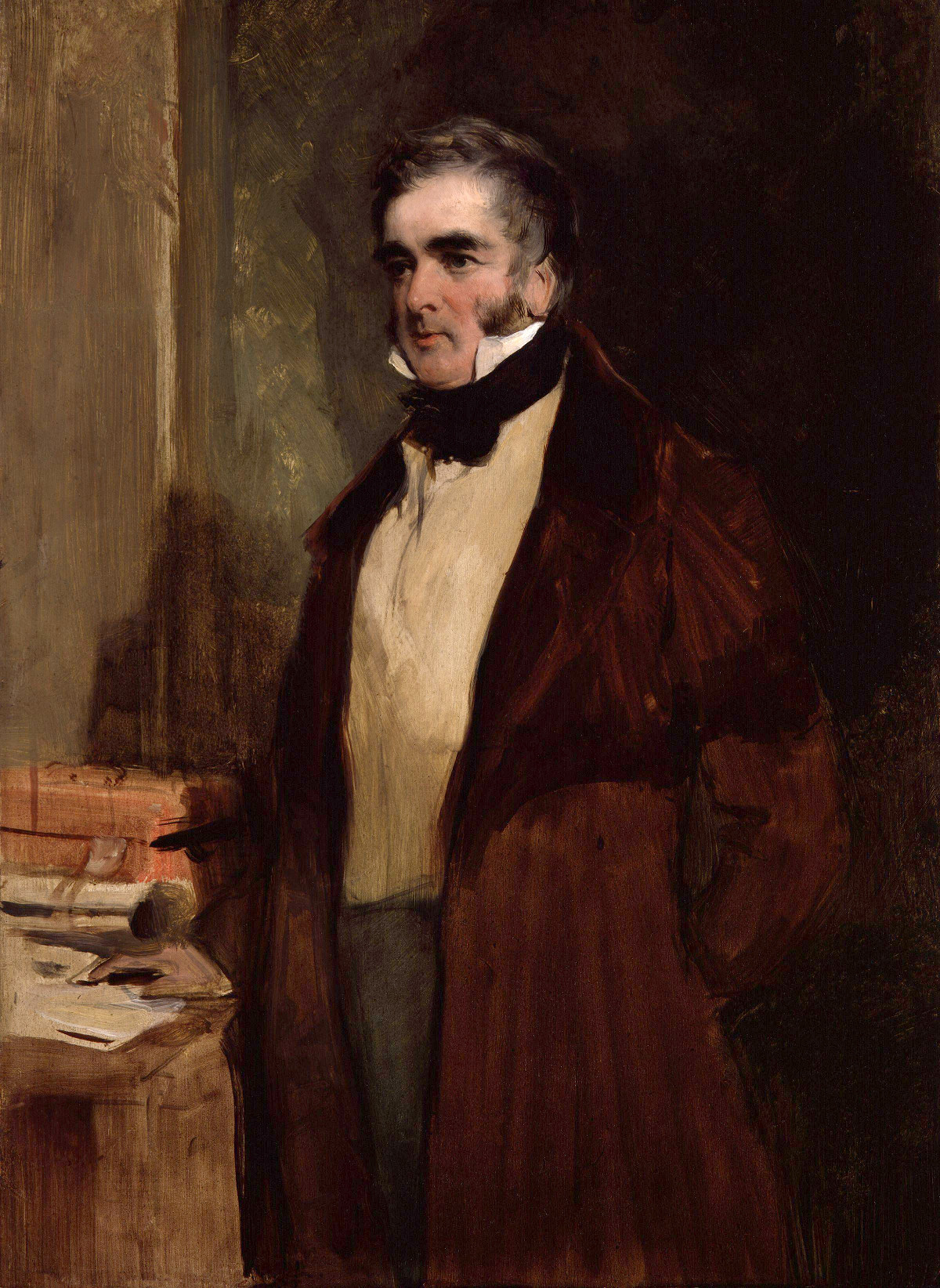

4. Lord Melbourne (1779 – 1848)

Serving as Home secretary and twice as Prime Minister, Lord “M”, as Victoria affectionately called him, is best known for mentoring her for the first three years of her reign.

As a younger man at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge, he made friends with Romantic poets Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron.

Whilst the association may have imbued him with some romantic charm, he later suffered great embarrassment and humiliation when his wife, Lady Caroline Ponsonby, had a public affair with Lord Byron.

Spending four or five hours a day visiting and corresponding with Victoria, tutoring her was the pinnacle of his career.

His influence faded when Victoria married Prince Albert and he died in retirement at Melbourne Hall in the Derbyshire countryside.

The city of Melbourne, Australia, was named in his honour in March 1837.

5. Rotten Row

A fashionable thoroughfare for upper-class Londoners to be seen horseriding, Rotten Row originally connected Kensington Palace with St James’s Palace.

Created by King William III and completed in 1690, Rotten Row was lit with 300 oil lamps and was the first artificially lit highway in Britain.

As can be seen at least twice in the Masterpiece first episode of Victoria, acquaintances would stop to chat on Rotten Row and the adjacent South Carriage Drive to bid each other good day.

Lord Melbourne is seen stopping on Rotten Row to chat with Lady Emma Portman and later, Sir Robert Peel.

Called “Route du Roi”, French for “King’s Road”, it became known by the nickname “Rotten Row”.

6. Everyone was “on the make”

This episode of Victoria highlighted just how much wheeling and dealing was at the centre of Victorian society at all levels.

While the upper classes sought to manipulate their way to political favors or plot the downfall of a rival, the working class was peddling anything they could to make ends meet.

From Queen Victoria’s used gloves to half-used candles, there was some serious rivalry to find “nice little earners” on the side.

Working as a servant in the royal household was a great privilege and considerably better paid than elsewhere.

A domestic servant in a modest household might earn about £12/year, whereas the lowest level in the palace received £15 15s/year.

We think we have it tough today, but at the beginning of Queen Victoria’s reign, an entry-level servant received the equivalent of £385/year (~$477/year). That’s £7.40/week ($9.16/week).

No wonder they were all “on the make”.

7. Uncle Cumberland

Every good drama has a villain. And Victoria is no exception.

The dastardly “Uncle Cumberland” aka Ernest Augustus, King of Hanover, makes a fine villain.

As the fifth son of George III, he thought he stood no chance of ever becoming monarch.

But fate works in mysterious ways.

None of his four elder brothers produced a legitimate heir who lived beyond infancy.

And so when his elder brother William IV died in 1837, he became king … of Hanover.

Hanover was part of the old Holy Roman Empire and honored “Salic Law”, barring women from succession.

Not so in the United Kingdom, where Victoria succeeded as next in line.

This must have rattled Uncle Cumberland quite a bit and so he plotted to have Victoria replaced by the co-regency of her mother and himself.

Completing the villainous look was a huge scar across his left eye that he received in 1793 from a sabre blow to the head.

Played down in most of his portraits, the damage to his eye is somewhat visible in the painting below from when he was 22 years old.

8. Victoria was no more than 5ft tall

A diminutive queen reigning over a mighty global empire must have seemed at odds to the taller males in the royal household.

To put things into perspective, even Napoleon Bonaparte, who was considered very short thanks to British propaganda (but was actually 5 ft 6″), would have stood a whole head taller than Victoria.

Masterpiece’s drama plays on Victoria’s height—from Lord Melbourne’s line “every inch a queen” to her feet dangling six inches from the floor as she sits on the old throne at Buckingham House.

Victoria may have been small in stature, but she was a giant in terms of the courage and willpower she showed to overcome such an oppressive childhood.

9. Buckingham House

Originally a townhouse built for the Duke of Buckingham in 1703, Buckingham Palace was once known as Buckingham House.

Acquired by King George III in 1761 as a residence for Queen Charlotte (when it was called “The Queen’s House”), Buckingham House was enlarged in the 19th century by the famous architect John Nash, who had been responsible for much of Regency London’s beautiful layout.

Becoming the principal royal residence in 1837, Queen Victoria was the first monarch to reside at Buckingham Palace.

Although the state rooms glowed with gilt and brightly colored semi-precious stones, the fireplaces were so ineffective that the palace was usually cold and drafty.

Today’s Buckingham Palace has 775 rooms and the largest private garden in London.

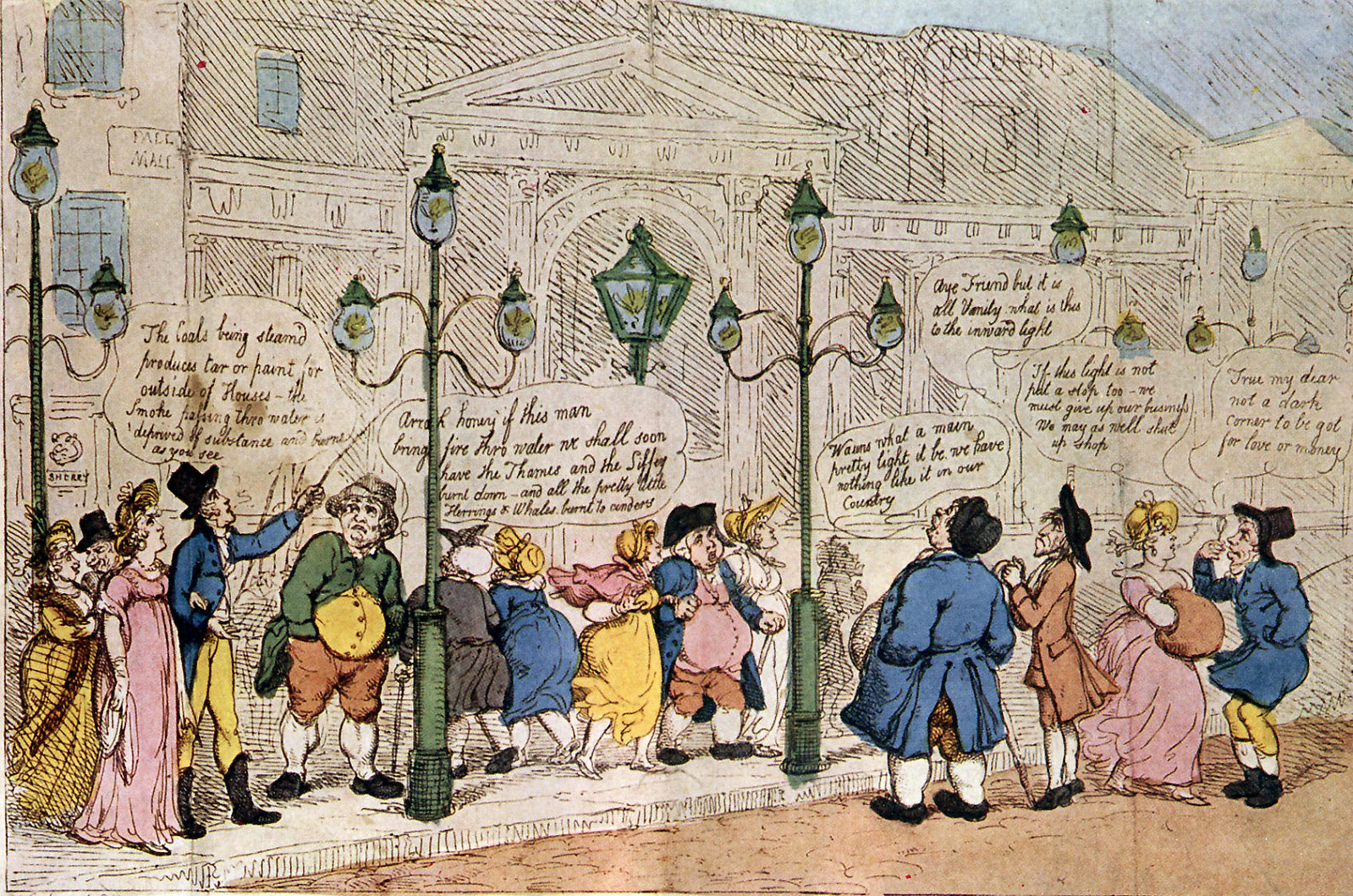

10. Candles and Gaslighting

Besides the staff making a “nice little earner” on half-used candles, we learned in the first Masterpiece episode of Victoria that shortly after her moving into the palace, gas lighting was installed.

In 1792, William Murdoch, a Scottish engineer and inventor, was the first to exploit the flammability of gas for the practical application of lighting.

By 1807, London’s Pall Mall was lit by gaslighting to celebrate the birthday of the Prince of Wales who later became King George IV.

Believed to help reduce crime, gas street lighting became widespread during the 1840s.

Along with new technology came new jobs as 380 lamplighters were employed by 1842 in London alone.

At the same time, Buckingham Palace and the new Houses of Parliament also went over to gas lighting.

Good ventilation was important for gas lighting because it consumed a lot of oxygen and since Buckingham Palace had such bad ventilation, there were serious concerns about gas build-up on lower floors.