Rising hundreds of feet above a rocky islet amidst vast sandbanks exposed to powerful tides stands a Gothic Benedictine abbey surrounded by a medieval village.

Built between the 11th and 16th centuries, Mont St Michel is a testament to the ingenuity of man inspired by God.

It takes your breath away.

Here are 10 fascinating facts about this incredible “island city”.

For added atmosphere, play the soundtrack.

1. Mont Saint-Michel was conceived in a dream

It was 708 A.D.

One night, Bishop Aubert of Avranches had a vision.

The Archangel Michael, who had defeated Satan in the war in heaven, appeared in a dream and instructed Aubert to build an oratory on the rocky island at the mouth of the Couesnon river.

“build it and they will come”

At first, Aubert ignored the vision, until the Archangel burned a hole in his head as a gentle reminder, whispering “build it and they will come”.

And come they did—pilgrims from all Christendom, and today, tourists from all corners of the world.

Aubert’s skull is displayed at the Saint-Gervais d’Avranches basilica bearing the scar of Michael.

Mont Saint-Michel soars 302 ft towards the heavens.

2. Mont Saint-Michel is a structural hierarchy of feudal society

On top, there is God, then the abbey and monastery; below this, the Great halls, then stores and housing, and at the bottom, outside the walls, the fishermen’s and farmers’ housing.

3. Mont Saint-Michel was one of the most important pilgrimage destinations

Second only to Santiago de Compostela in Spain, Mont-Saint Michel was an important pilgrimage of faith during the Middle Ages.

Such was the difficulty of the journey that it became a test of penitence, sacrifice, and commitment to God to reach the Benedictine abbey.

Chosen by Richard II, Duke of Normandy, the Italian architect, William of Volpiano, designed the Romanesque church of the abbey, daringly placing the transept crossing at the top of the mount.

Many underground crypts and chapels had to be built to compensate for this weight, forming the foundation for the supportive upward structure that we see today.

Standing separate, not linking the abbey buildings, the cloister is a place to meditate, with the fragrance of herbs, flowers, and the sea filling the air.

Nestled at the foot of the abbey in the main street, the parish church of Église Saint-Pierre (Church of St Peter) is a little gem often overlooked by visitors.

When the abbey was secularised in the 19th century, the church became the focus of the pilgrimages to Mont Saint-Michel.

4. The English couldn’t conquer Mont Saint-Michel

During the Hundred Years’ War, the Kingdom of England made repeated assaults on the island but were unable to seize it due to the abbey’s strong fortifications.

Besieging the Mont in 1423–24, and then again in 1433–34, the English forces under the command of Thomas de Scales, 7th Baron Scales abandoned two wrought-iron bombards (cannon) when he gave up his siege.

Known as “les Michelettes”, they remain on site to mark the impenetrable fortress protected by God.

5. Mont Saint-Michel inspired Joan of Arc to victory

When news of the island’s stand against the English reached a young peasant girl in Orléans, south-west of Paris, the tide would turn against England in the Hundred Years’ War.

That girl was Joan of Arc, and so inspired was she at the story of resistance at Mont St Michel, she would help recapture France from the English.

6. Mont St Michel has a counterpart in Cornwall, England

In 1067, the monastery of Mont Saint-Michel gave its support to William the Conqueror in his claim to the throne of England.

Rewarding the monastery with properties and grounds on the English side of the Channel, he included a small island off the southwestern coast of Cornwall which was modeled after the Mount and became a Norman priory named St Michael’s Mount of Penzance.

The two mounts share the same tidal island characteristics and the same conical shape, though St Michael’s Mount is much smaller.

7. Mont Saint-Michel served as a prison

With its popularity and prestige as a center of pilgrimage waning during the Reformation, by the time of the French Revolution, there were very few monks in residence.

Closed in 1791, the abbey was converted into a prison, initially holding clerical opponents of the republican regime—up to 300 priests at one point.

Nicknamed “bastille des mers”, meaning “Bastille of the sea”, it was named after the fortress in Paris that served as a state prison during the Ancien Regime.

Serving as a windlass, a treadwheel crane helped hoist supplies high up to the prison walls.

Prisoners would rotate the wheel by walking inside it like hamsters.

Treadmill cranes were commonly used for lifting heavy objects on medieval construction sites.

After a series of high profile political prisoners were held at Mont Saint-Michel, influential figures, including Victor Hugo, launched a campaign to restore what they felt was a national architectural treasure.

Closing the prison in 1863, Napoleon III ordered the 650 prisoners to be transferred to other facilities.

8. Mont Saint Michel has deadly tides

Popularly nicknamed “St. Michael in peril of the sea” by medieval pilgrims making their way across the flats, the tides can vary by as much as 46 ft between high and low water marks.

Connected to the mainland by a modern causeway built in 2014, the tide poses dangers for visitors who choose to walk across the sands—threatened by a tide that is said to travel at the speed of a galloping horse.

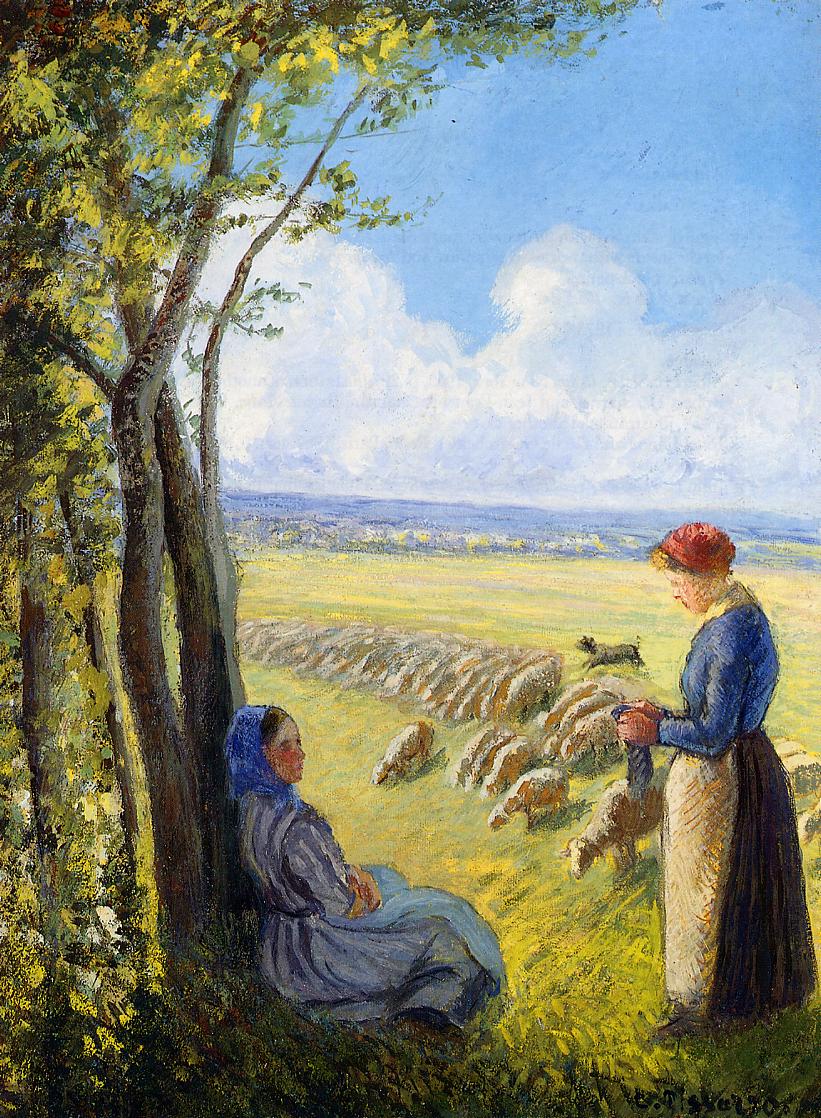

Polderisation and occasional flooding have created salt marsh meadows that are ideally suited to grazing sheep.

Richly-flavored meat resulting from the sheep’s diet in the “salt meadow” makes a dish called agneau de pré-salé “salt meadow lamb”, a local specialty served on the menus of restaurants at the mount.

9. Mont Saint-Michel and its bay are UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1979, Mont Saint Michel and its 11th-century Benedictine abbey have become a favored destination for pilgrims and tourists alike.

10. Mont Saint-Michel is a top cultural attraction

Barely bigger than its gothic abbey, the island is cut off from land twice a day at high tide and yet attracts more than 3 million visitors a year.

Enjoy the video as seen from where only a drone can go!