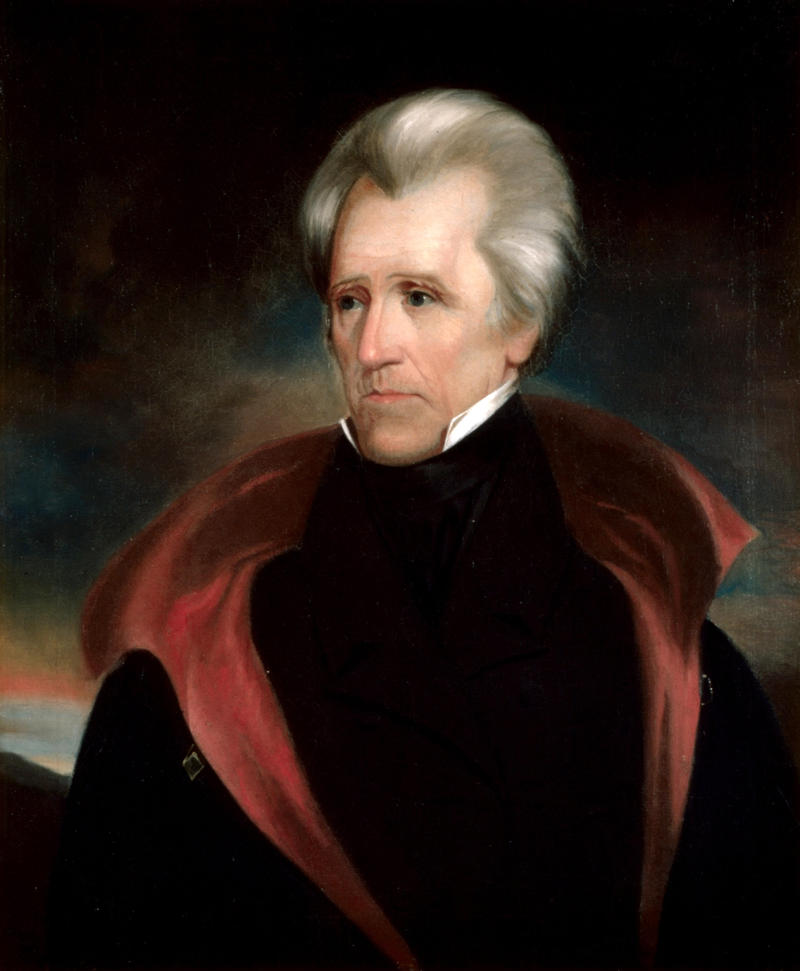

The French still cannot agree on whether Napoleon was a hero or a tyrant.

In a 2010 opinion poll, French people were asked who was the most important man in French history. General Charles de Gaulle, who governed Free France from exile during the German occupation in World War II was voted number one, followed by Napoleon.

Only two statues commemorate Napoleon in Paris: one beneath the clock tower at Les Invalides (a military hospital), the other atop a column in the Place Vendôme. No grand boulevard, square, or place bears Napoleon’s name. Just a narrow street—the rue Bonaparte.

“It’s almost as if Napoleon Bonaparte is not part of the national story,” said professor Peter Hicks, a British historian with the Napoléon Foundation in Paris.

Join me as we explore some of the reasons why Napoleon was such a controversial figure.

Then vote below whether you think Napoleon was a hero or a tyrant.

Napoleon the Hero vs Napoleon the Tyrant

Napoleon the Hero

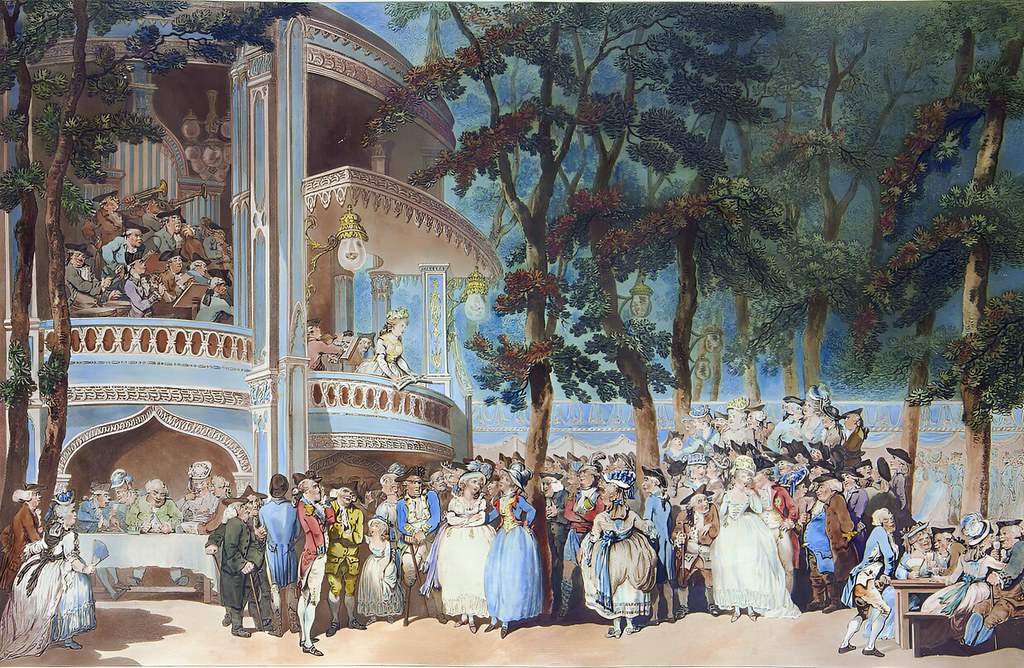

Napoleon enthusiast David Chanteranne, editor of a magazine published by Napoléonic Memory, France’s oldest and largest Napoleonic association, cites some of Napoleon’s achievements: the Civil Code, the Council of State, the Bank of France, the National Audit office, a centralized and coherent administrative system, lycées, universities, centers of advanced learning known as école normale, chambers of commerce, the metric system and freedom of religion.

Many of the institutions started by Napoleon were copied in countries that he conquered—Italy, Germany, and Poland, and laid the foundations for the modern state.

The University of France was a central organizing body for education founded by Napoleon in 1808 and given authority over universities as well as primary and secondary education.

Napoleon set in motion a system of secular and public education reforms that are the foundation for the modern educational system in France and much of Europe. He founded a number of state secondary schools, called lycées, to provide a standardized education open to everyone. All students were taught the sciences, plus modern and classical languages. Advanced centers—notably the École Polytechnique—provided both military expertise and state-of-the-art research in science. The system offered scholarships and strict discipline and outperformed its European counterparts.

The Lycée Louis-le-Grand is a public secondary school located in Paris, widely regarded as one of the most prestigious in France.

Napoleon is considered one of the greatest commanders in history—his campaigns are studied at military schools worldwide. Hundreds of groups study, discuss and venerate him; stage re-enactments of his battles in costume; throw lavish balls; and stage events. Napoleon was regarded by the influential military theorist Carl von Clausewitz as a genius in the operational art of war, and historians rank him as a great military commander. The Duke of Wellington, when asked who was the greatest general of the day, answered: “In this age, in past ages, in any age, Napoleon.” Israeli military historian and theorist, Martin van Creveld, described him as “the most competent human being who ever lived”.

Across Europe, Napoleon implemented several liberal reforms to civil affairs, including abolishing feudalism, establishing legal equality, religious toleration, and legalizing divorce. His lasting achievement, the Napoleonic Code, has been adopted by dozens of nations around the world. The Code forbade birthright privilege, granted freedom of religion and specified that government jobs should be awarded on merit alone.

Prior to the Napoleonic Code, France did not have a single set of laws; the law was based on local customs, exemptions, privileges, and special charters granted by kings or other feudal lords. Although the Code has been altered since its inception, the general structure remains the same.

Napoleon implemented a wide array of liberal reforms in France and across Europe, especially in Italy and Germany, as summarized by British historian Andrew Roberts in his book Napoleon: A Life, p.33:

Andrew Roberts also claims that, contrary to popular belief, Napoleon wasn’t a warmonger. He started two wars—the Peninsula War against Portugal and Spain, and later the Invasion of Russia—versus seven coalition wars declared against Napoleonic France.

In 1806, Napoleon emancipated Jews, (as well as Protestants in Catholic countries and Catholics in Protestant countries), from laws restricting them to ghettos, expanding their rights to property, worship, and careers.

Weakness in the French economy during the 1790’s caused a drop in foreign trade and soaring prices. Inflation and debt escalated with the issuance of more paper money until, by 1795, inflation reached 3500%. In 1800, Napoleon founded the Bank of France, which together with a revised tax code, finally brought inflation under control, eliminated the national debt within a year and balanced the budget for the first time since 1738.

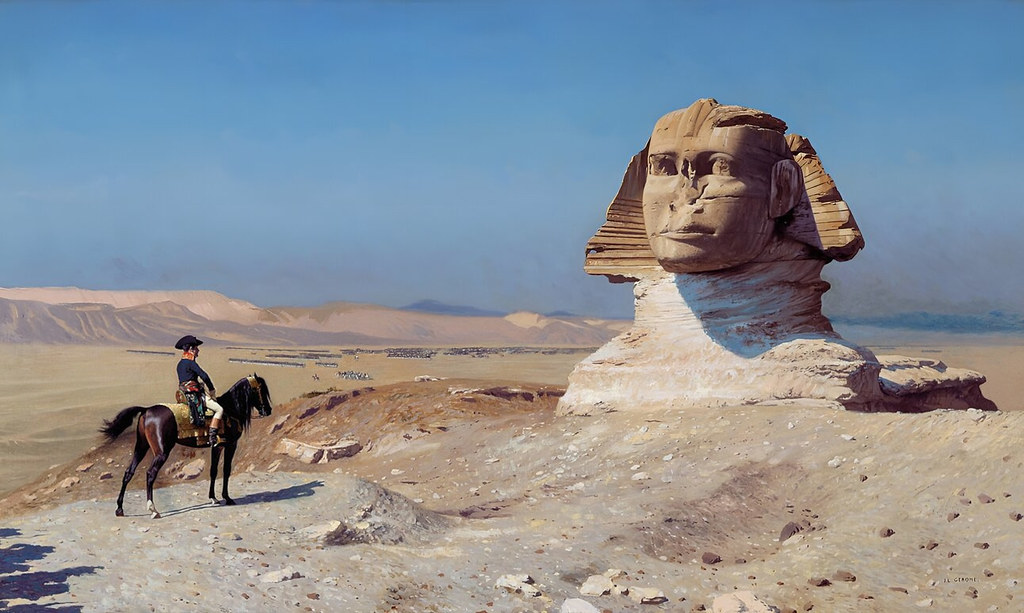

After conquering Egypt in the expedition of 1798, Napoleon founded the Institut d’Égypte. Accompanying the voyage was an immense contingent of scholars, scientists, artists, and engravers who set about studying mummies, surveying temples, and recording their findings. They produced a monumental 24-volume document called Description of Egypt—a comprehensive scientific account of ancient and modern Egypt, which laid the foundation for the study of “Egyptology”. They also discovered the Rosetta Stone, which proved to be the key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphics.

The last word goes to France’s foremost Napoleonic scholar, Jean Tulard, who said that Bonaparte was the architect of modern France.

Napoleon the Tyrant

Professor Chris Clark, a Cambridge University historian, said of Napoleon:

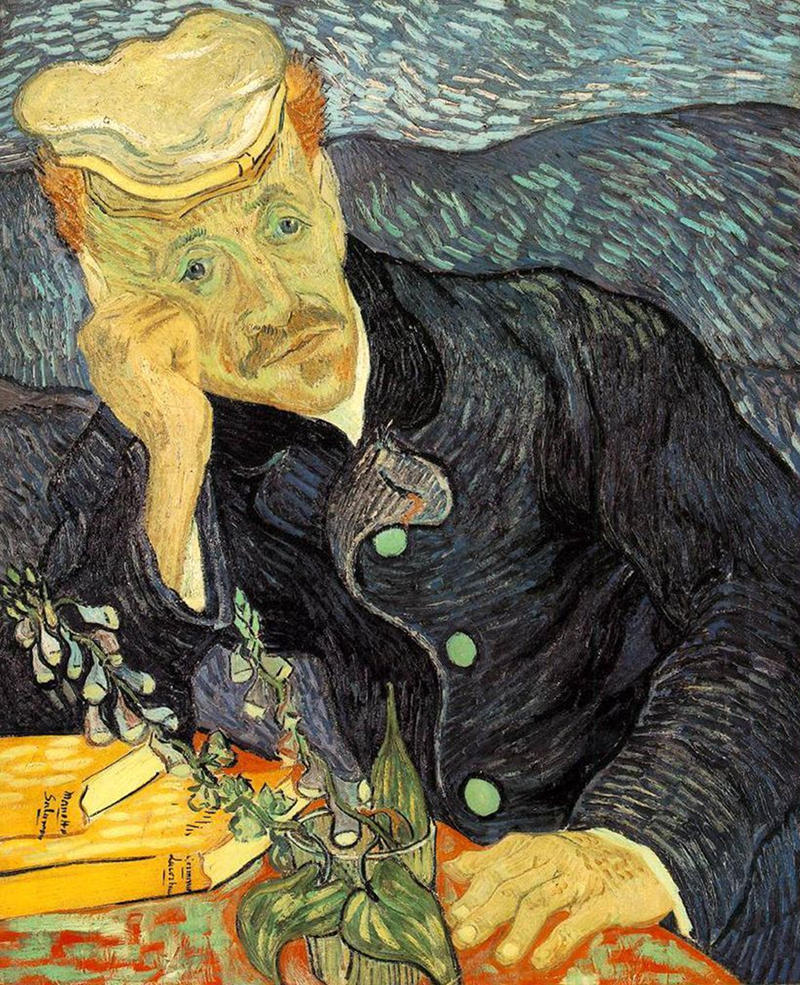

Napoleon tried to represent himself as a Caesar: his coronation crown was a laurel wreath made of gold; his icon, the eagle, was also borrowed from Rome; and he wears a Roman toga on the bas-reliefs in his tomb.

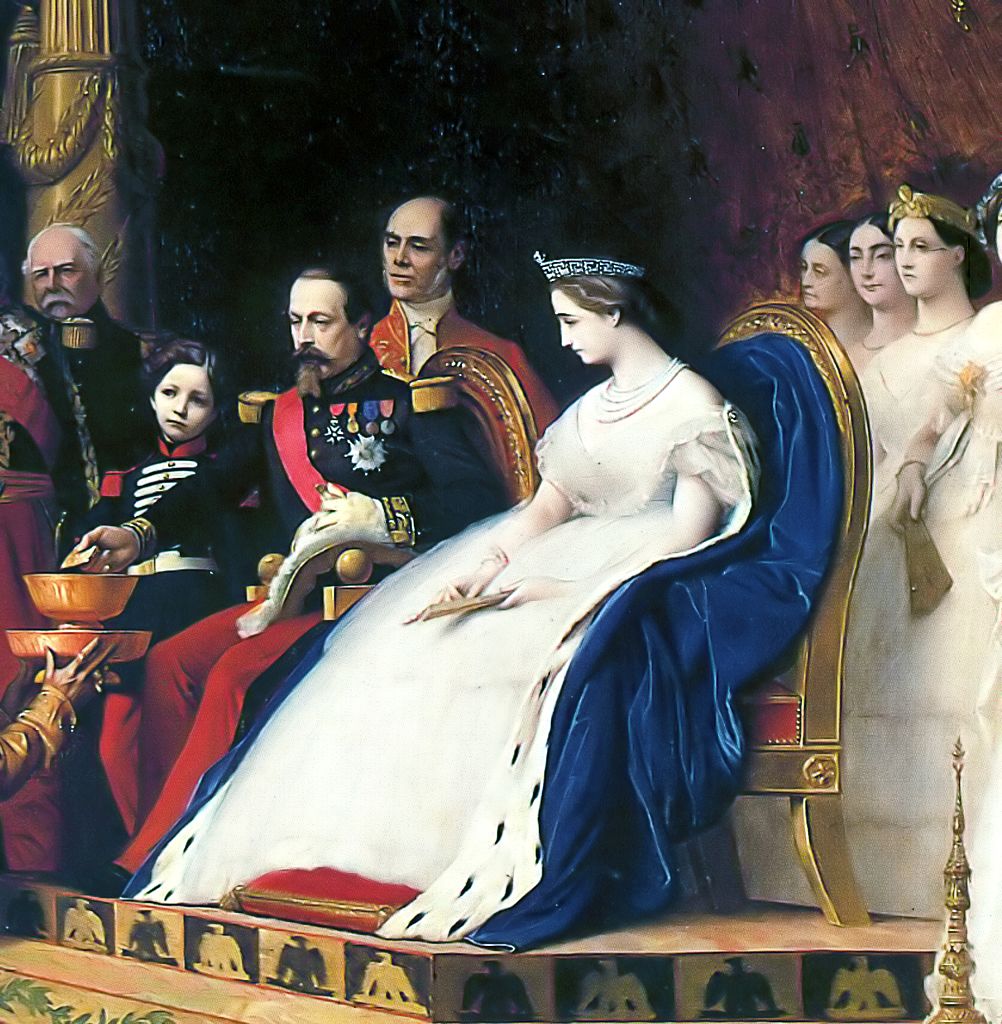

Before crowning himself emperor, Napoleon sought approval in a rigged plebiscite in which 3,572,329 voted in favor, 2,567 against. A plebiscite was a national referendum, for which voters were not allowed to debate the issues involved. Napoleon didn’t trust voters’ opinions, so he had his loyal agents count the votes to make sure the results came out as desired. Furthermore, each “yes” or “no” was recorded, along with the name and address of the voter. The minister of police, Joseph Fouché, promptly suppressed any criticism. The combination of a ruthless police state and rigged elections became a staple of populist dictatorial regimes to the present.

Napoleon personally oversaw the productions of plays in the theaters of France. If Napoleon disapproved of a playwright’s work, his career was over. Napoleon also controlled the press, dropping the number of newspapers in Paris from over sixty in 1799 to four by 1814.

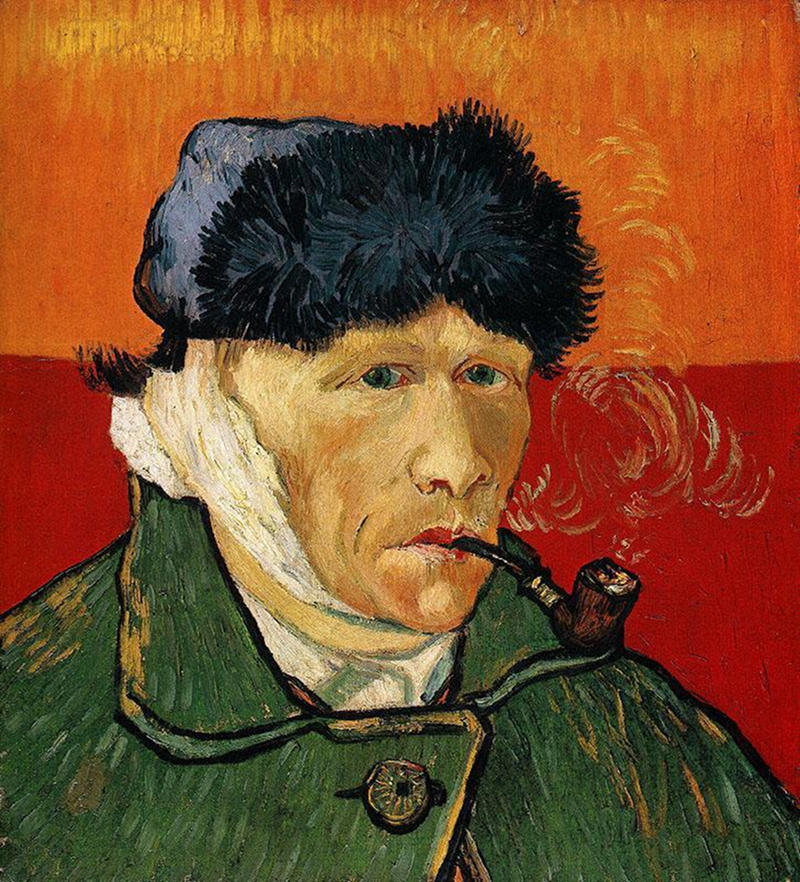

Considered a master of the use of propaganda, Napoleon recognized the power of manipulation of symbols to glorify his victories while blaming others for his failures. Like Caesar before him, he self-congratulated his military exploits and created the image of a dashing commander. Napoleon understood how to convince the population that sacrifice for one’s emperor and nation were more important than the rights of the individual. This is how he was able to assemble such large armies, no matter how bad things were.

His extravagant coronation in Notre Dame in December 1804 cost 8.5 million francs or $8.5 million in today’s money. He made his brothers, sisters and stepchildren kings, queens, princes and princesses and created a Napoleonic aristocracy numbering 3,500. By any measure, it was a bizarre progression for someone often described as “a child of the Revolution.”

“He guaranteed some principles of the revolution and at the same time, changed its course, finished it and betrayed it,” said Lionel Jospin, the Socialist former prime minister and author of The Napoleonic Evil, which has topped the best-seller lists. For instance, Napoleon reintroduced slavery in French colonies, revived a system that allowed the rich to dodge conscription in the military and did nothing to advance gender equality.

The grandiose image Napoleon created for himself, as well as the tightly controlled society that he established once in power, was a model for a totalitarian state that Hitler and Stalin would follow with such ruthlessness in the next century. Those who deified him were crushed under his iron hand. Joseph Fouche, the head of the secret police, extending Emperor Napoleon’s reach into every aspect of French society through a vast network of spies. Jean-Paul Bertaud, a Professor Emeritus of History at La Sorbonne in Paris, and a specialist on the French Revolution and military history explained what life was like under Napoleon’s iron rule:

Napoleon had no qualms about killing French citizens. In 1795, he mowed down the Parisian mob with cannons, an event known as the 13 Vendémiaire. He showed no hesitation in using extreme force to quell the uprising with what became known as “a whiff of grapeshot”—deadly slugs of metal packed into bags or canisters, then fired into the mob at close range, ripping through flesh with terrifying effectiveness.

In a PBS documentary, Owen Connelly Professor of History at The University of South Carolina said:

Napoleon was famously worshiped by his troops, but did he return their loyalty? During the Egyptian campaign of 1798-1801, Bonaparte’s failed siege of the fortified city of Acre (now Akko in modern Israel) left his army poorly supplied and weakened by disease—mostly bubonic plague. To hasten the retreat back to Egypt, he ordered plague-stricken men to be poisoned. He later abandoned the remainder of his army—some 30,000—secretly returning to France to a hero’s welcome, while his loyal army remained in Egypt to fend for themselves. In exile on St Helena, he said:

Later in 1812, Napoleon ignored advice from his closest advisors and invaded Russia. A doomed campaign, his inflated ego cost the lives of some 500,000 men, most dying not from fighting, but from starvation, sickness, and exposure during the long retreat back to France. When rumors of a coup in Paris reached him, he once again abandoned what remained of the Grande Armée—from the 600,000 men he took into Russia, only 93,000 survived.

As Napoleon’s power waned, his censorship was no longer able to hide his failures. He needed victories on the battlefield in order to maintain control of his empire. After his eventual defeat, his soldiers still considered him their true leader and helped him regain control of France. Under Napoleon’s command, he promised to raise them and make them all heroes once again.

The last word goes to former French Prime Minister Lionel Jospin from an article in Newsweek:

Hero or Tyrant? Cast Your Vote.

References (Contains some Amazon affiliate links)

Why Napoleon’s Still a Problem in France – Newsweek.

Napoleon – PBS.

Napoleon: A Biography – Frank McLynn.

Reforms Under Napoleon Bonaparte – Nicholas Stark.

Napoleon – Wikipedia.

A Short History of Europe – Lisa Rosner, John Theibault

Napoleon and the Revolution – David P. Jordan