Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, was a French aristocrat and military officer.

To many of us, he is simply the famous Frenchman who fought in the American Revolutionary War.

But there is much more to this amazing man than meets the eye.

Here are 10 fascinating facts about the Marquis de Lafayette that you may not be aware of.

1

Lafayette was made a King’s Musketeer at age thirteen

At just 13 years old, Lafayette entered the King’s Musketeers as a junior commissioned officer.

He was in exalted company alongside legendary musketeers like Charles de Batz de Castelmore d’Artagnan—the real-life historical basis for Alexandre Dumas’s character d’Artagnan in the novel The Three Musketeers.

Reserved for nobles, the Musketeers were among the most prestigious of the military companies of the Ancien Régime—the old political and social system that had been in place in France since the late Middle Ages.

Founded in 1622 to guard the king while he was outside of the royal residences, the uniform changed from the flamboyant cavalier style of d’Artagnon to the more utilitarian dress that Lafayette would have worn (shown as the two central figures below).

In 1664, the two companies were reorganized into “Grey Musketeers”, from the color of their matched horses, and “Black Musketeers”, mounted on black horses.

Lafayette’s six years in the Black Musketeers must have served him well for what lay ahead.

2

Lafayette was instrumental in the outcome of the American Revolutionary War

Not only was Lafayette effective as a military officer with hands-on engagement in several battles, for which he was commended by Washington himself, he was also instrumental in securing French finance, troops, and ships to aid the American cause.

Charming, tall, and idealistic, the 19-year-old Lafayette had defied the French king’s orders and enlisted to fight in America for the prospect of glory, chivalry, and liberty.

Shot in the leg at his first battle at Brandywine Creek in Pennsylvania, it wasn’t long before Lafayette was back on his feet again, spending the winter of 1777 camped at Valley Forge alongside Washington and the Continental Army.

Starvation, disease, malnutrition, and exposure killed more than 2,500 American soldiers by the end of February 1778.

Despite his privileged aristocratic upbringing, Lafayette willingly endured the hardship along with everyone else.

So severe were the conditions at times that even Washington was in despair.

A year later, Lafayette returned to France, where his wife Adrienne gave birth to a son they named Georges Washington Lafayette.

And he also secured the promise of 6,000 French troops.

Lafayette sailed for America once more in March of 1780 in the frigate Hermione.

3

Lafayette became an American citizen before becoming a French citizen

After the Revolutionary War in 1784, Lafayette visited America again.

He met Washington at Mount Vernon, addressed the Virginia House of Delegates and the Pennsylvania Legislature, and went to the Mohawk Valley in New York to help make peace with the Iroquois.

For his troubles and gratitude for his selfless service during the war, Harvard granted him an honorary degree, and the states of Maryland, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Virginia granted him American citizenship.

Lafayette later boasted that he had become an American citizen before the concept of French citizenship even existed.

4

Lafayette was a lifelong abolitionist

Lafayette was a staunch opponent to the concept of slavery.

His writing was adopted as part of the French Constitution and included revolutionary ideas such as the freedom and equality of all men.

Although his work never specifically mentioned slavery, he made his views clear in letters to George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.

Hoping that Washington and Jefferson might adopt his ideas to free the slaves in America, he proffered that slaves could be made free tenants on the land of plantation owners.

But his ideas fell on deaf ears, so in 1785, he bought a plantation in the French colony of Cayenne to put his experimental ideas into practice.

A lifetime abolitionist, he was also a pragmatist and recognized the crucial role slavery played in many economies.

George Washington did eventually begin implementing Lafayette’s practices in his own plantation in Mount Vernon.

And Lafayette’s own grandson, Gustave de Beaumont later released a novel discussing the issues of racism.

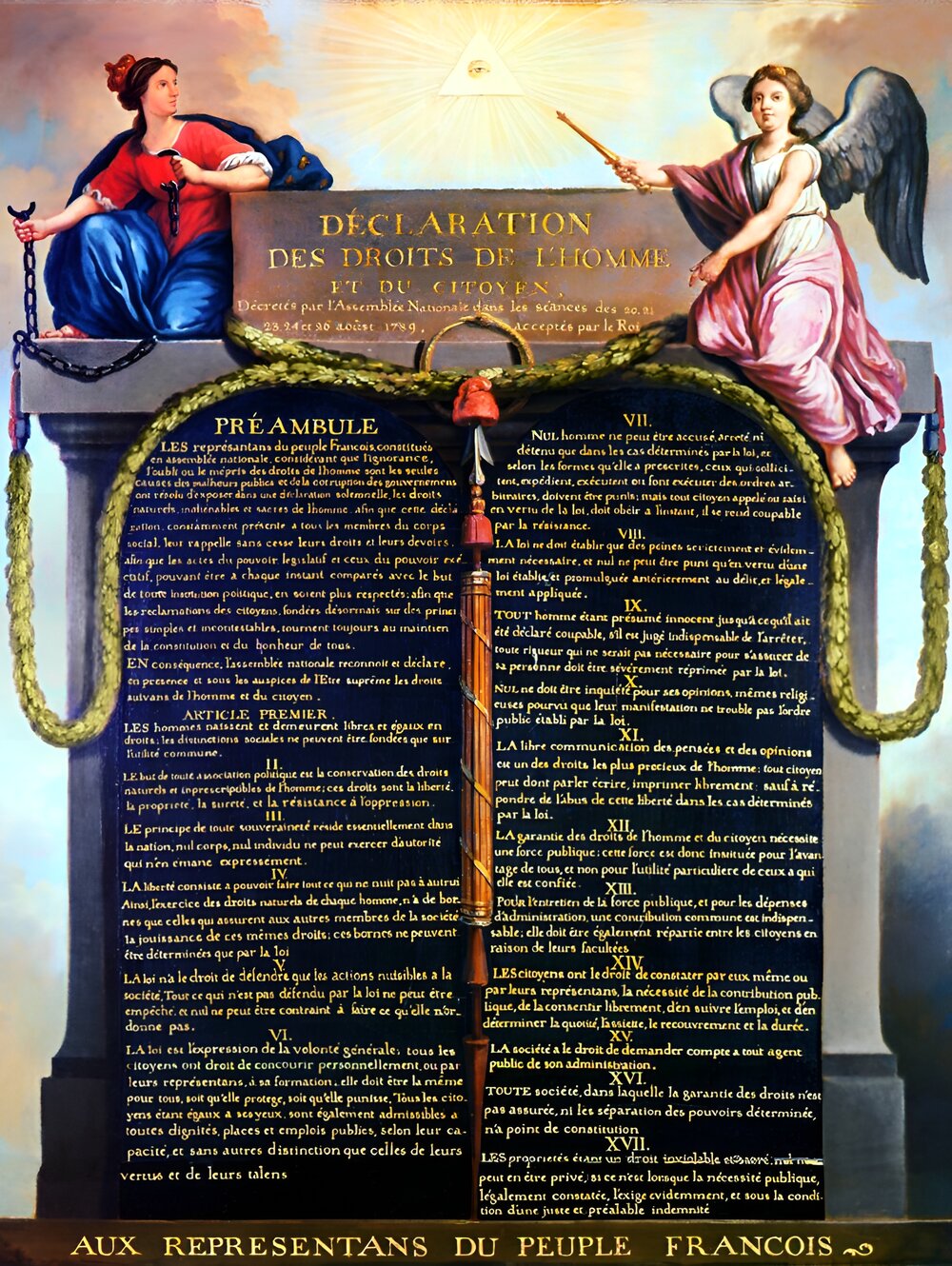

One of Lafayette’s publications was monumental in expediting France’s abolition of slavery in 1794—the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

5

Lafayette helped write the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

Passed by Frances’ National Constituent Assembly in August 1789, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen is an important document in the history of human and civil rights.

Directly influenced by Thomas Jefferson, it states that the rights of man are held to be universal and valid at all times and in every place.

It became the basis for a nation of free individuals protected equally by the law.

Inspired by the Enlightenment, the Declaration provided the rationale for the French Revolution and had a major impact on the development of freedom and democracy in Europe and worldwide.

6

Lafayette created the French Tricolor

After the French Revolution broke out, Lafayette was appointed commander-in-chief of the National Guard of France, tasked with maintaining order.

He proposed a new symbol for the Guard: a blue, white, and red cockade.

Combining the red and blue colors of Paris with the royal white, it was the origin of the French tricolor.

7

Lafayette and his family narrowly escaped execution in the French Revolution

As the French Revolution deepened, it became ever more extreme.

Lafayette had tried to maintain order and steer a middle ground.

But when radicals asserted control, a Reign of Terror ensued that swept even Lafayette into mortal danger.

Lafayette criticized the growing influence of the radicals and called for their parties to be “closed down by force”.

It was a risky move in the political climate of the time.

An escape attempt by King Louis XVI and his family dubbed the “Flight to Varennes” had extremists like Georges Danton pointing the finger at Lafayette for allowing it to happen on his watch.

And one of the most influential figures of all—Maximilien Robespierre—labeled Lafayette a traitor.

Sensing the public mood had changed against him, Lafayette left Paris and Danton put out a warrant for his arrest.

8

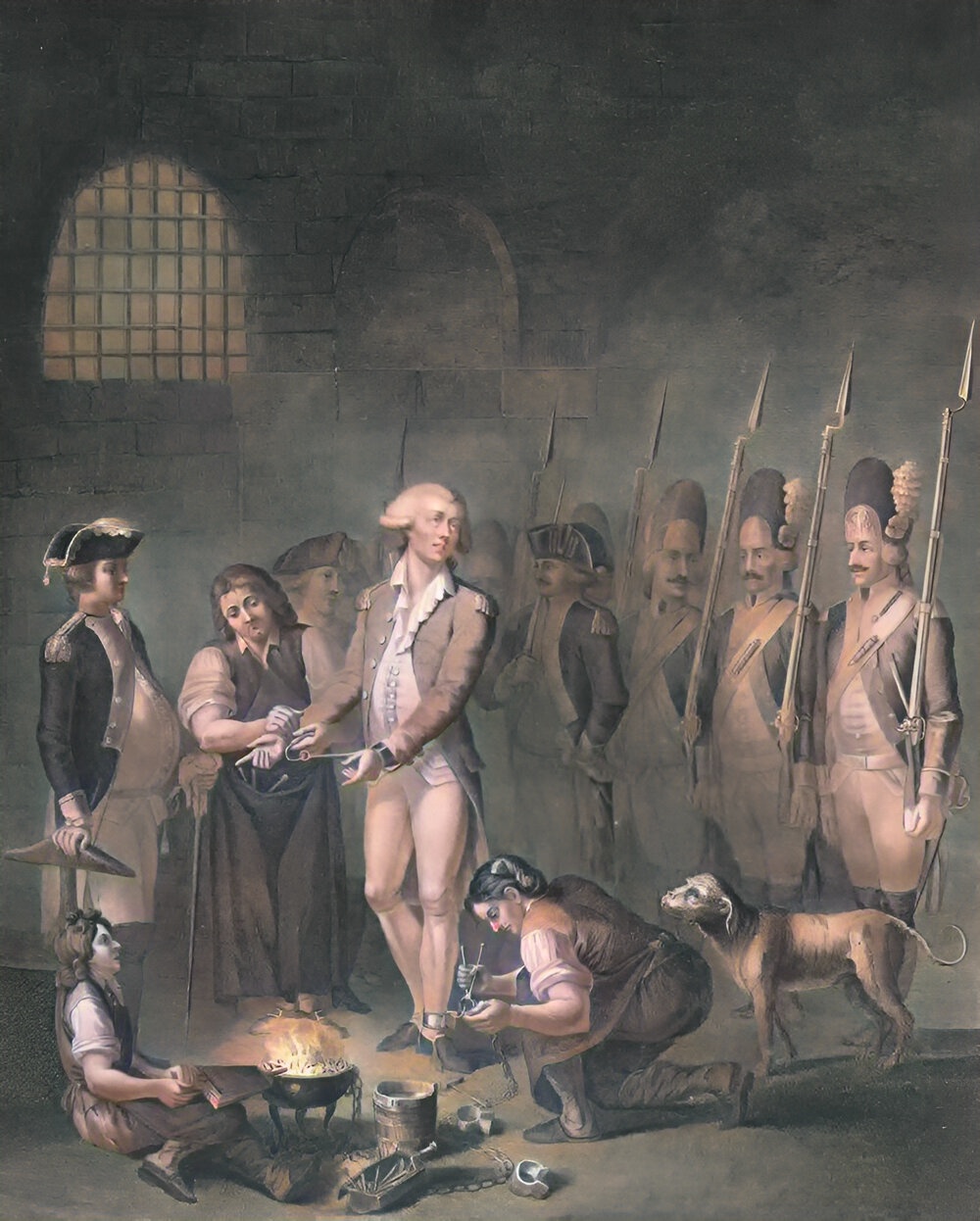

Lafayette spent 5 years in prison

Hoping to return to the United States, Lafayette traveled through the Austrian Netherlands in what is now Belgium.

Expecting right of passage as a fleeing refugee, Lafayette’s luck ran out when he was recognized by the Austrians and treated as a dangerous revolutionary.

Held prisoner until such time as the monarchy was reinstated in France, he tried to use his American citizenship to secure his release.

Although unsuccessful, Washington and Jefferson were able to use diplomatic loopholes to get money to Lafayette, which he was able to use to secure his family’s safety.

U.S. Minister to France and future president, James Monroe used his influence to win the release of Lafayette’s wife Adrienne and their two daughters.

9

Lafayette’s reputation was used to gain support for entry into World War I

Lafayette’s name and image were repeatedly invoked in 1917 in seeking to gain popular support for America’s entry into World War I.

In a speech given in Paris during the First World War, Charles E. Stanton included a memorable expression that would become the famous phrase, “Lafayette, we are here.”

Stanton visited the tomb of Lafayette along with General John J. Pershing to honor the nobleman’s assistance during the Revolutionary War and assure the French people that the people of the United States would aid them in World War I.

Sadly, Lafayette’s image suffered as a result when veterans returned from the front singing “We’ve paid our debt to Lafayette, who the hell do we owe now?”

10

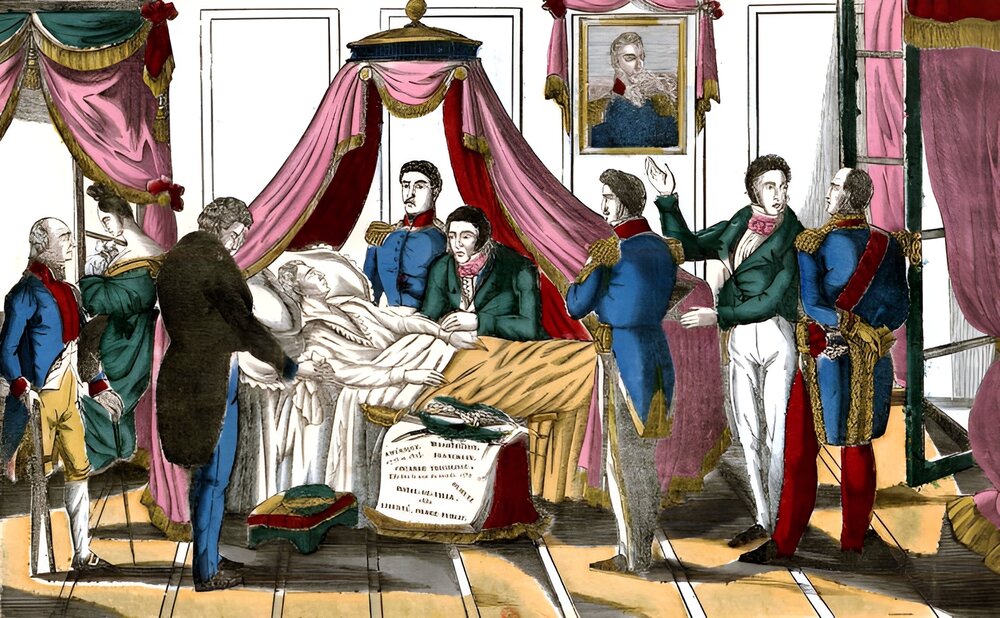

Lafayette is buried under soil taken from Bunker Hill

Lafayette died on 20 May 1834, and is buried in Picpus Cemetery in Paris, under soil taken from Bunker Hill.

For his accomplishments in the service of both France and the United States, he is sometimes known as “The Hero of the Two Worlds“.

American journalist, historian, and author, Marc Leepson, concluded his study of Lafayette’s life: