It was 10:02 in the morning, August 27th, 1883.

The loudest explosion ever recorded and heard by humans was about to tear the Indonesian island of Krakatoa apart.

Anyone within 10 miles was instantly deafened as white-hot molten pumice and gases blasted twenty-four miles into the stratosphere.

With explosive power 13,000 times greater than the atomic bomb that destroyed Hiroshima, Krakatoa devastated the region with a death toll recorded at 36,417, although some sources put the estimate at more than 120,000.

Numerous reports cite groups of human skeletons floating across the Indian Ocean on rafts of volcanic pumice and washing up on African shores up to a year later.

Average global temperatures fell by as much as 1.2 degrees Celsius in the year following the eruption. Weather patterns continued to be chaotic for years.

1.2 degrees of cooling doesn’t sound like much, does it? After all, the temperature fluctuates by many degrees every day.

The key is the global average temperature. It’s an average of the entire surface of the planet. Although regional temperatures can vary widely, the global average usually doesn’t change by much.

A one-degree global change is significant because it takes a vast amount of heat to warm all the oceans, atmosphere, and land.

In the past, a one- to two-degree drop was all it took to plunge the Earth into the Little Ice Age. And 20,000 years ago, a five-degree drop was enough to bury a large part of North America under a towering mass of ice.

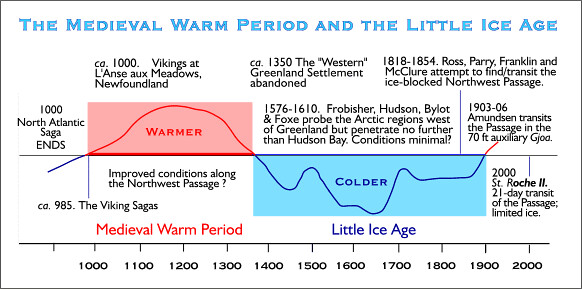

Scientists believe the earth goes through temperature cycles, like those shown in this chart.

Much of the medieval period was warmer than average—allowing Vikings to settle in otherwise inhospitable places like Greenland and Newfoundland. But when temperatures cooled again from around 1350, the Vikings had to abandon these far-flung settlements.

In addition to Krakatoa, another even larger Indonesian volcano—Mount Tambora—erupted earlier in 1815, emitting enormous amounts of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere that blocked incoming sunlight, leading to the “Year Without a Summer” in 1816.

High levels of tephra in the atmosphere caused moodier, darker sunsets, which caught the attention of several artists, including Caspar David Friedrich.

Did Tambora and Krakatoa both contribute to lowering average temperatures for Victorians? Does this help explain why Victorians were able to wear so many layers of clothing, even in summer?

Let’s look at some of the evidence provided by temperature records, photographs, and paintings.

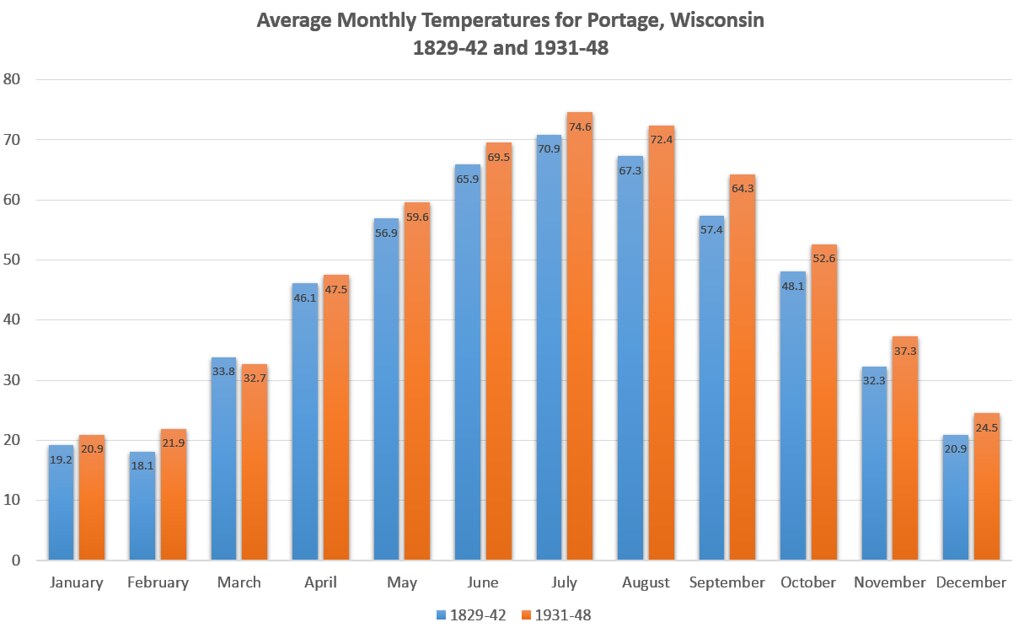

The chart below compares temperature records for Portage, Wisconsin for two periods 100 years apart. Every month apart from March was a lower temperature in 1829-42 than for 1931-48—sometimes lower by as much as 5-7 degrees.

This group of women is wearing heavy Victorian clothing with crinolines in Queensland, Australia—a province that today has an average summer temperature of 30°C (86°F).

Here we see Victorians in an English south coast resort dressed in coats and hats. It is clearly sunny because women are using parasols to protect their skin from the sun’s rays. Was the summer temperature considerably milder than today?

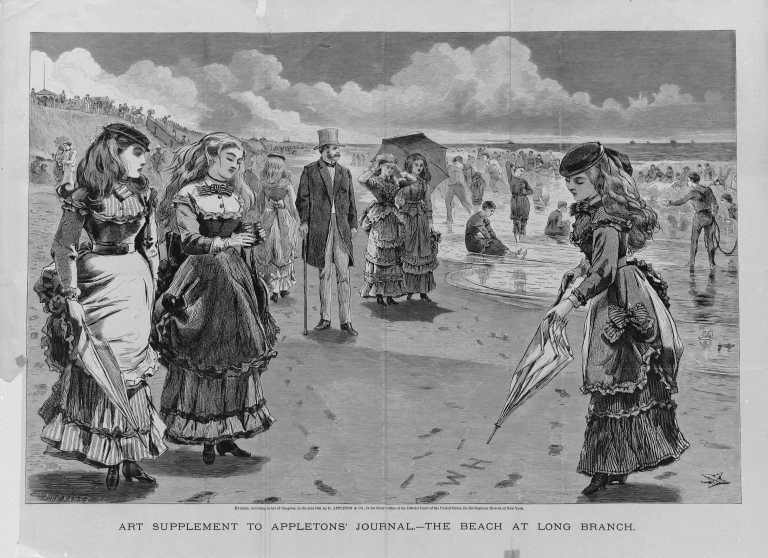

In this 1869 illustration of New Jersey’s Long Branch—the “Hollywood” of the east—we see clothing that today would be considered more appropriate for winter than summer.

This group of missionaries is posing in the tropics of Africa for this photograph. How are they able to tolerate wearing such clothing in the tropical heat? Could it have been a few degrees cooler than today?

Another American beach, this time in Gloucester, MA, with people dressed in multiple layers of clothing. The skies are overcast. Was this typical weather?

French painter Eugène Louis Boudin was one of the first French landscape painters to paint outdoors—becoming expert at rendering seascapes. Here, he offers us a glimpse of beach life at Trouville in France from 1867 – 1870. The familiar sight of men and women wearing ample layers of clothing is common to all three paintings.

The temperature data, photographic, and artistic evidence do seem to support a theory that Victorians experienced lower than average global temperatures as part of a cool period in the weather cycle.

Finally, let’s look at some anecdotal evidence of how the lower global temperatures might have affected the weather. There was certainly no shortage of shipwrecks during the Victorian period.

And consider the title of this painting from 1873—”The Gust of Wind.”

If this was merely a “gust”, just imagine what a real storm would have been like!

Suggested Reading

The following images connect you with Amazon and contain Affiliate links, which means we may earn a small commission from qualifying purchases. Thanks for supporting our work.