From Christian martyrs to Chaucer to Shakespeare, Valentine’s Day can be traced back to Ancient Rome, but it is the Victorians who made it into the holiday we know today.

A British Valentine

Victorian Valentine cards were flat paper sheets, often printed with colored illustrations and embossed borders. The sheets, when folded and sealed with wax, could be mailed.

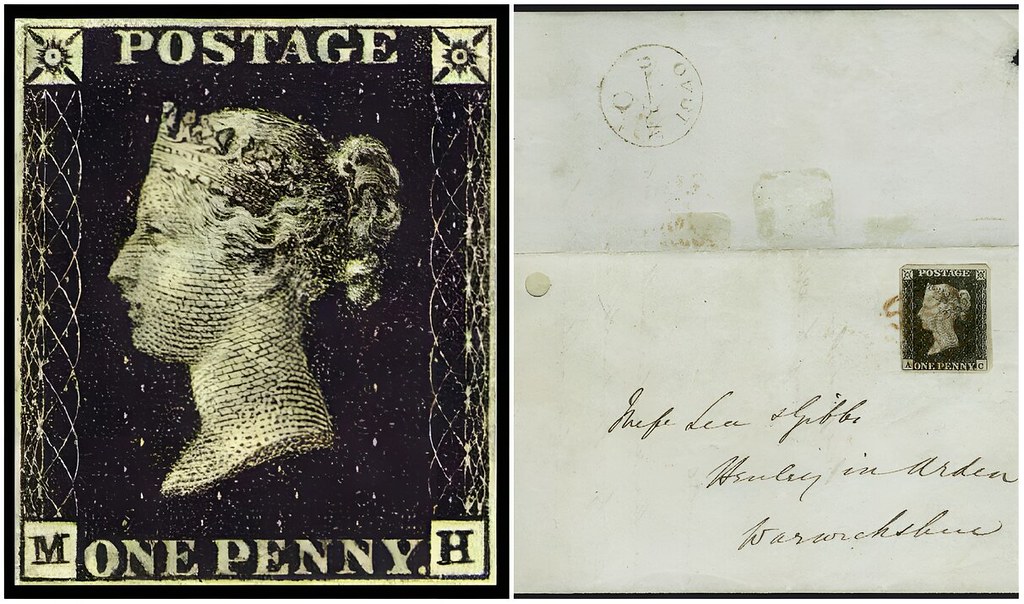

In 1837, a government postal official named Rowland Hill published a seminal pamphlet: Post Office Reform; Its Importance and Practicability.

Hill is credited with inventing the postage stamp and originating the modern postal service.

He observed that postal charges were by distance and by the number of pages, rather than by weight.

To send one sheet from London to Edinburgh cost 1s 1½d, which was more than a days wage for the working class, and almost 14 times the actual cost to the Post Office.

On 10 January 1840, Great Britain introduced the Uniform Penny Post, meaning that Valentine cards could be mailed for just one penny. The mass produced Valentine card was born.

Valentines were sent in such great numbers that postmen were given a special allowance for refreshments to help them through the extraordinary exertions of the two or three days leading up to February 14th.

Just one year after the Uniform Penny Postage, 400,000 valentines were posted throughout England. By 1871, 1.2 million cards were processed by the General Post Office in London.

A popular poem of the time, by James Beaton, alludes to the mass popularity of Valentine Cards.

Postmen may judge them by the lot, they won’t have time to count;

They must bring round spades and measures, to poor love-sick souls

Deliver them by bushels, the same as they do coals.

Rather than purchase a ready-made valentine, some Victorians assembled original valentines from materials purchased at a stationer’s shop: lace, bits of mirror, bows and ribbons, seashells and seeds, gold and silver foil appliqués, silk flowers, and clichéd printed mottoes like “Be Mine” and “Constant and True.”

Victorian valentines commonly feature churches or church spires, signifying honorable intentions and fidelity.

The cards, often handmade, featured lace, pressed grass and Valentine’s jokes.

One card, titled “The Bark of Love”, featured a fairy in a gilded carriage drawn by two swans.

Another, rather saucy card, featured what is possibly a pair of Victorian undergarments, with the message, “I think of you with inexpressible delight”.

An American Valentine

Esther Howland (1828–1904), known as the “Mother of the American Valentine”, was an artist and businesswoman who is responsible for popularizing Valentine’s Day greeting cards in America.

During her college years, students often secretly exchanged poems elaborately scrawled on sheets of paper.

After she graduated, Howland received an ornate English Valentine from a business associate of her father when she was 19 years old.

Elaborate Valentine greeting cards were imported from Europe and not affordable to many Americans.

She wanted to change that and started importing paper lace and floral decorations from England to make her own cards.

By the mid-1850s Valentine’s Day cards were so popular that the New York Times published sharp criticism on February 14, 1856:

In any case, whether decent or indecent, they only please the silly and give the vicious an opportunity to develop their propensities and place them, anonymously, before the comparatively virtuous.

The custom with us has no useful feature, and the sooner it is abolished the better.

The sending of Valentine Cards in the US didn’t pick up pace until after the Civil War.

On February 4, 1867, the New York Times wrote that in 1862 post offices in New York City had accepted 21,260 Valentines for delivery. 1863 showed a slight increase, but the number fell to 15,924 the year after.

However, in 1865, perhaps with bitter memories of the war starting to fade, New Yorkers mailed more than 66,000 Valentines, and more than 86,000 the following year.

Valentine’s Day was truly becoming big business. According to the New York times, some New Yorkers paid exorbitant prices for Valentines:

There is a tradition that one of the Broadway dealers not many years ago disposed of no less than seven Valentines which cost $500 each, and it may be safely asserted that if any individual was so simple as to wish to expend ten times that sum upon one of these missives, some enterprising manufacturer would find a way to accommodate him.

Queen Victoria’s Valentine

The question of whether Queen Victoria had a romantic attachment to her man servant John Brown – or even married him in secret – is often hotly debated in the British press today.

In her letters and journal, Queen Victoria called John Brown “darling one” and wrote, ” … so often I told him no one loved him more than I did or had a better friend than me: and he answered ‘Nor you — than me … No one loves you more'”

Queen Victoria sent Valentines Day cards to John Brown, which were said to be of such “cloying winsomeness” and “artlessness” that some believe they stand as evidence of how innocent their relationship was.

Victorian Valentines: 1840 – 1900.

References

- The Bath Postal Museum: The History of the Postal Services

- Norfolk Museums: The History of Valentine Cards

- Smithsonian’s National Postal blog: Love and Derision; Or, Valentine’s Day Victorian Style

- Yallambie: Love Makes the World Go Round, About

- History Extra: Victorian Valentine’s Day Cards

- Wikipedia: Esther Howland

- About.com: Cards for St. Valentine’s Day Became a Tradition in the 1800s