It was the winter of 1843.

Long after the sober folks had gone to bed, Charles Dickens paced the streets of London.

Unaware of time and place, he would walk fifteen or twenty miles many a night, his head filled with thoughts about his latest project.

It was nearly finished.

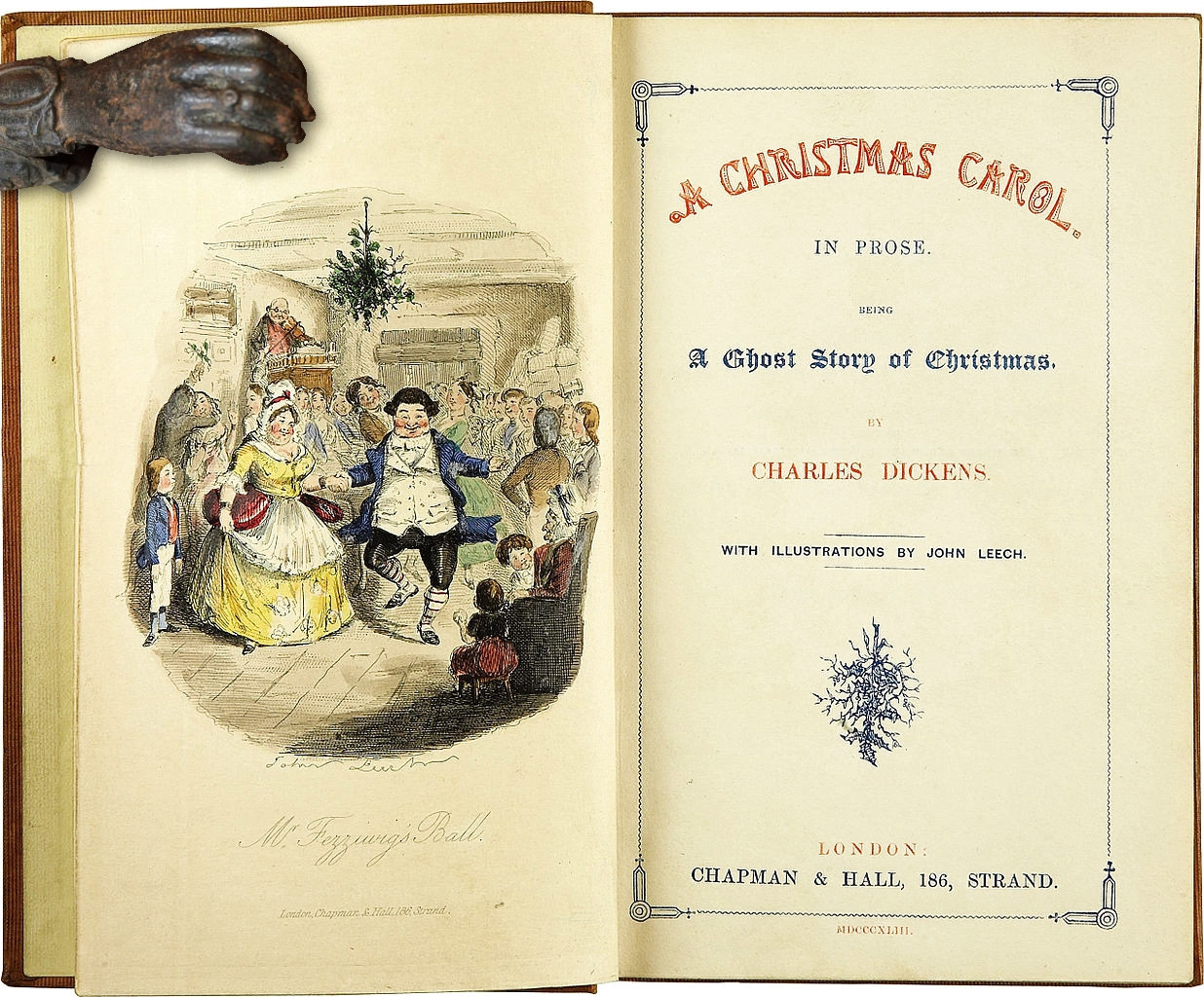

A Christmas Carol was born of an idea that the best way to bring about awareness for the plight of the poor was through story.

Dickens had considered writing pamphlets and essays, but these were not the ways to reach people’s hearts.

People loved stories.

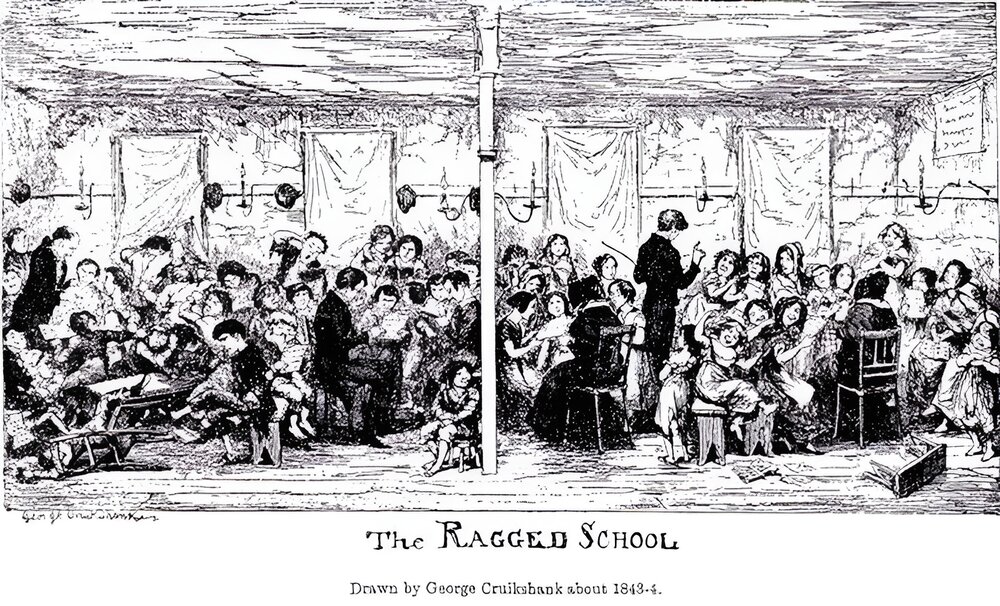

A few weeks earlier, his friend the Baroness Burdett-Coutts had considered donating to the system of religiously-inspired schools known as the “Ragged Schools”.

She had asked Dickens if he would visit the school at Saffron Hill in London and relay his impressions.

Dickens was shocked with what he saw.

It was his personal experience that imbued him with a sense of duty to help the poor.

Growing up, his father, John Dickens, was imprisoned in Marshalsea debtors prison, while Charles was forced to leave school and work in a blacking factory.

Before the Bankruptcy Act of 1869, debtors in England were routinely imprisoned at the pleasure of their creditors.

Memories of this period would haunt Dickens for the rest of his life.

Although he loved his father, he saw in him a cold-hearted miser, inspiring the dual characters of Ebenezer Scrooge.

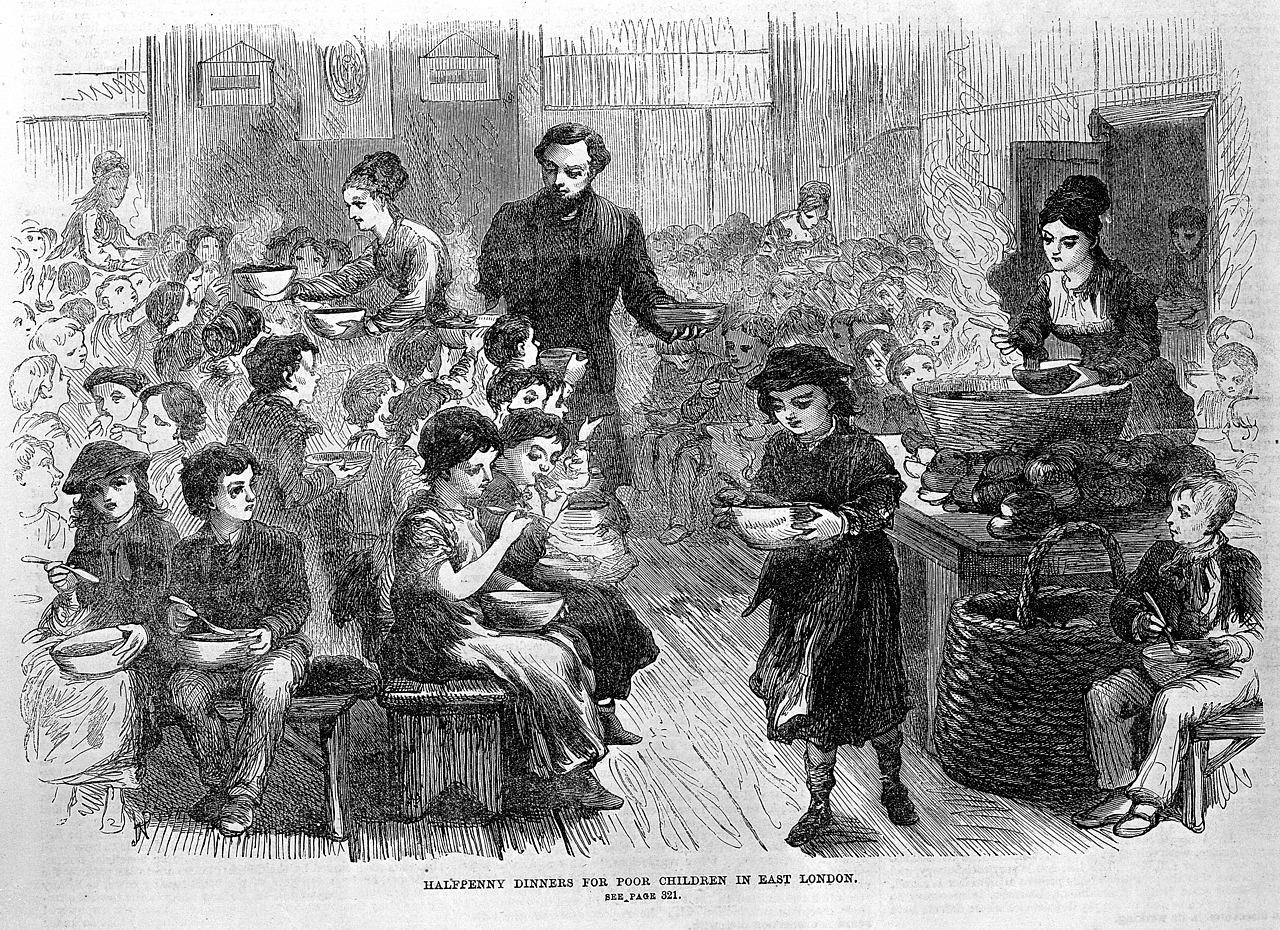

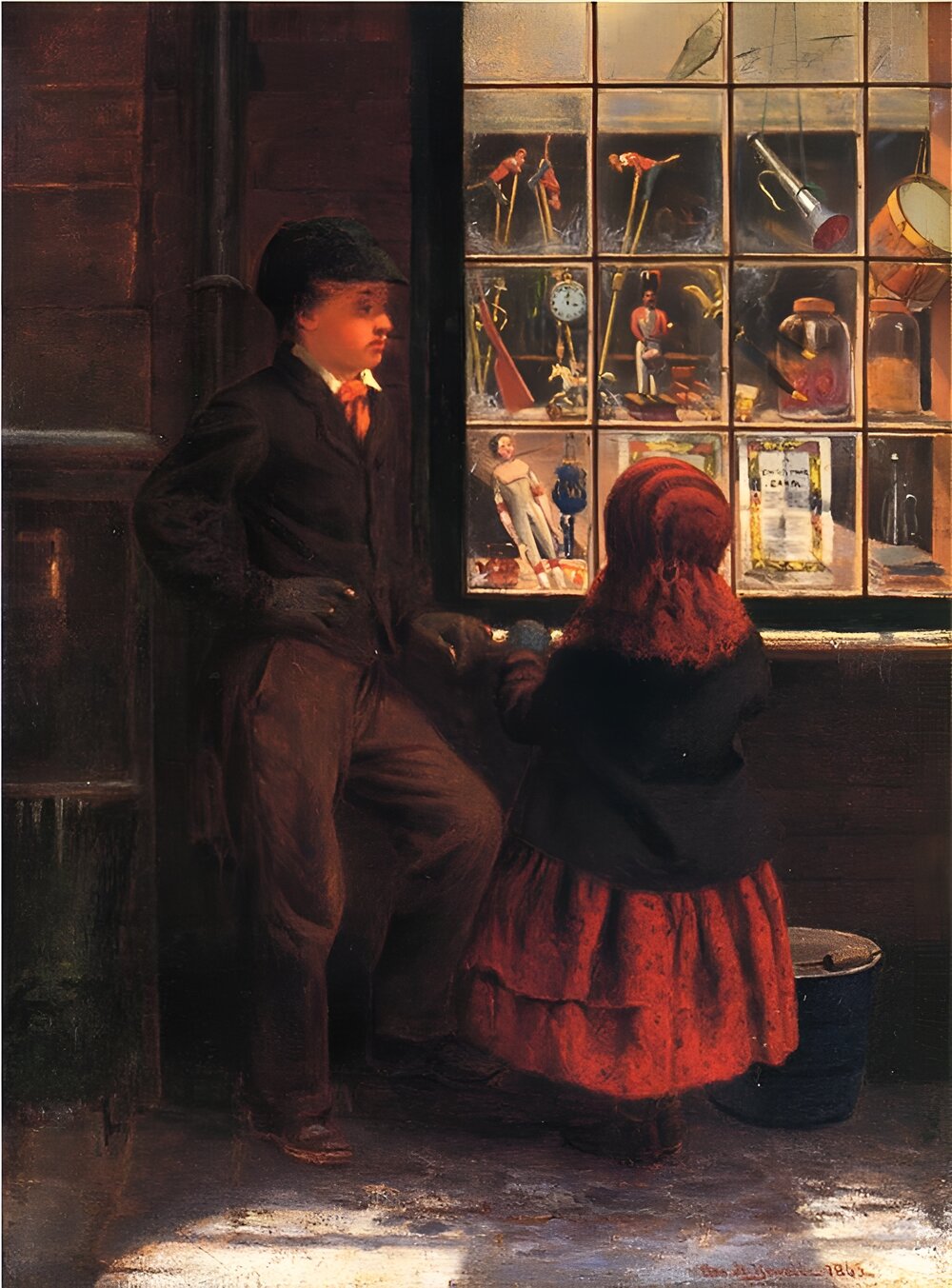

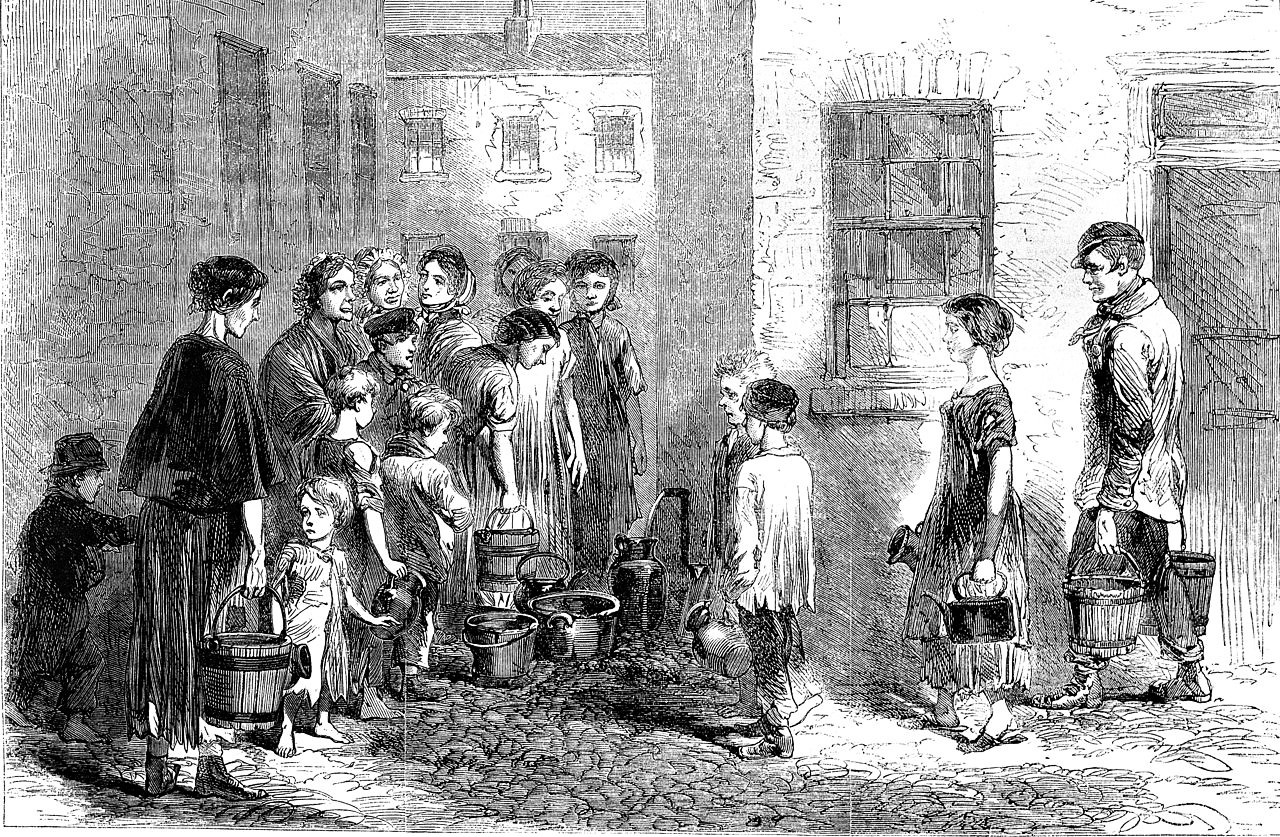

Victorian London was experiencing an economic boom, but one that left the poor behind.

Moving to London in search of opportunity from the harsh agrarian life in the country, many became disappointed, disillusioned, and destitute.

The industrial revolution brought huge wealth to a tiny percentage of the population, with the majority scraping a living in damp, noisy factories, and cramped, filthy slums.

Dickens and the Baroness felt that education was the solution. At least it gave hope even to the poorest of families that their children might one day break the mould of poverty and join the rising middle class.

With the Saffron Hill Ragged School still playing on his mind, in October of 1843 Dickens visited a workingmen’s educational institute in the industrial city of Manchester, England.

It was here that Dickens had his “eureka moment”.

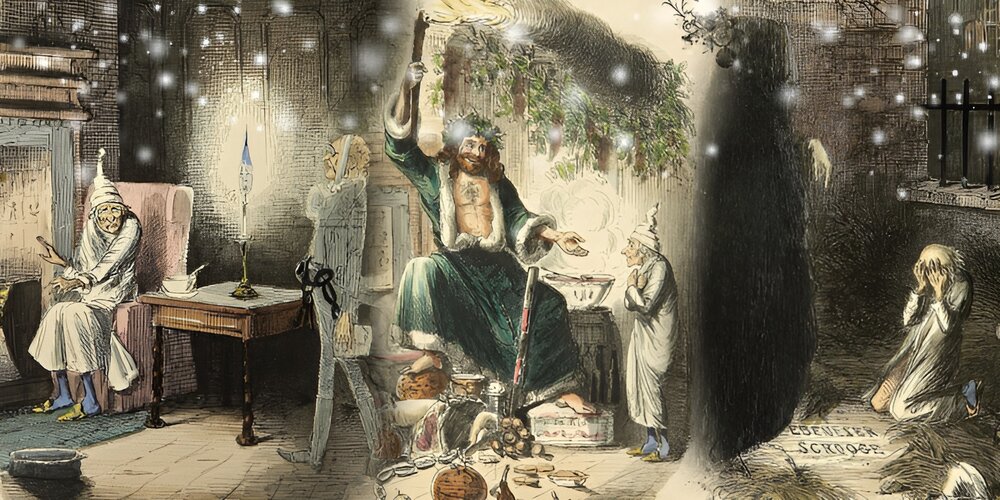

Instead of writing a journalistic piece on the plight of the poor, he would write a ghost story—A Christmas Carol.

Through story, Dickens asked for people to recognize the plight of those whom the Industrial Revolution had displaced and driven into poverty, and the obligation of society to provide for them humanely.

Critical praise poured in.

Scottish writer Margaret Oliphant described it as “a new gospel”.

The impact was astounding.

In the spring of 1844, there was a sudden burst of charitable giving in Britain.

Scottish philosopher and writer, Thomas Carlyle, staged two Christmas dinners after reading the book.

After attending a reading on Christmas Eve in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1867, a Mr Fairbanks closed his factory on Christmas Day and sent every employee a turkey.

British stage actor Sir Squire Bancroft raised £20,000 for the poor by reading A Christmas Carol out loud in public.

With today’s information revolution displacing many livelihoods, the story is as relevant as it was for Charles Dickens.

In advocating the humanitarian focus of the Christmas holiday, Dickens influenced many aspects that are celebrated in Western culture today—family gatherings, seasonal food and drink, dancing, games and a festive generosity of spirit.

At this time of feasting, let us reflect on A Christmas Carol and the social movement it inspired.