It was the year 1828.

In the little English village of Polstead in Suffolk, Mrs. Marten was having a bad dream.

A ghostly figure appeared to her, pointing to a spot on the ground.

The ghost was her missing stepdaughter, and the place she pointed to was inside the Red Barn, a local landmark.

Waking in a panic, she nudged her husband, the young woman’s father, beckoning him to go to the Red Barn and dig near one of the grain storage bins.

Reluctantly, her husband went out into the yard to fetch a shovel before making his way over to the Red Barn.

Buried in a sack he found the badly decomposed remains of his daughter, Maria, still recognizable from her hair and clothing.

An inquest concluded that she had been murdered.

Implicated by evidence found with the body, the prime suspect was one William Corder, the man Maria was supposed to have eloped with.

But Corder was nowhere to be found.

By all accounts, William Corder, the son of a local farmer, was something of a fraudster and a ladies’ man.

Called “Foxey” at school because of his sly manner, he had been found guilty of forgery and stealing in his youth.

Banished to London for bringing disgrace to his family, he would return to Polstead when his brother Thomas drowned attempting to cross a frozen pond.

And when his father and three brothers all died within the following 18 months, he had to run the family farm alone with his mother.

Corder started seeing Maria Marten, an attractive woman who was known for several relationships with men from the neighbourhood that had already resulted in two children.

The first had been fathered by Corder’s own brother, but had died in infancy, and the second from a man who refused to marry her but sent money every month to provide for the child.

Having children out of wedlock was a social taboo and so it was with some regret that Maria announced to Corder that she was pregnant.

Corder promised to do the decent thing and marry her.

But secretly, he was hatching a dastardly plan.

In the presence of her mother, he proposed to Maria that they elope, explaining that he had heard rumours about officers preparing to prosecute her for having children out of wedlock.

Maria heard nothing from him for a few days, then he arrived at her cottage saying they must leave at once because the local constable had a warrant for her arrest.

Corder took Maria’s things and told her to dress in men’s clothing to avert suspicion, then meet him at the Red Barn about a half mile away, where she could change before they eloped.

That was the last time Maria was seen alive.

Corder himself disappeared from the village but later returned, explaining that they were married and that Maria was staying in a nearby town because he needed to explain the situation to his friends and relatives before introducing her as his wife.

Days passed and suspicions grew as Maria did not return to the village.

Corder fled but wrote letters to Maria’s family explaining that they were living happily on the Isle of Wight, some 200 miles away.

He gave excuses as to why she hadn’t written herself, saying she was not well, her letters must have been lost, or that she’d injured her hand.

It wouldn’t be too long before Corder was discovered, leading a double life with another woman in London.

Placing an ad in the lonely hearts column of the Times newspaper, he had met and married another woman, Mary Moore, and was helping her run a boarding house.

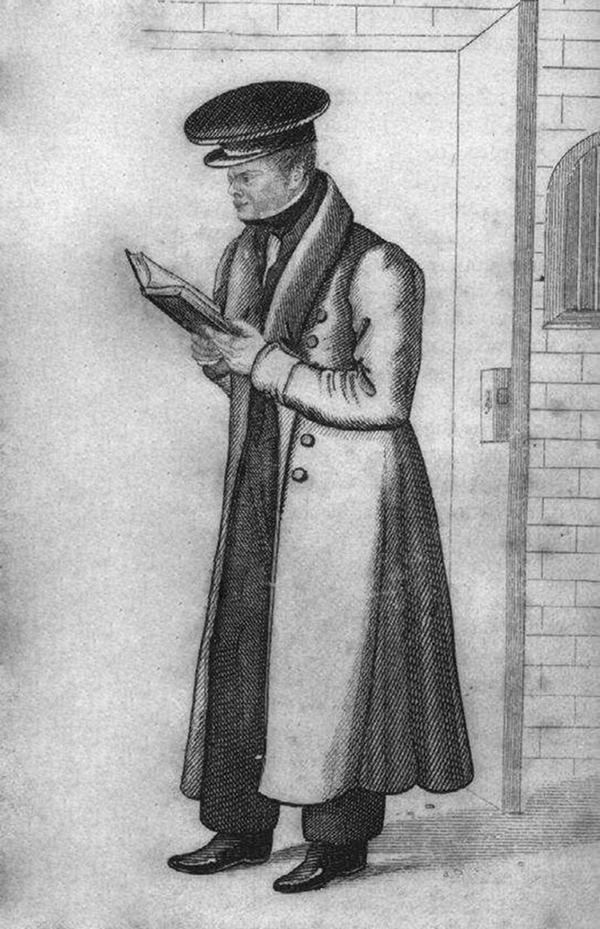

Officer James Lea of the London police inquired about boarding his daughter there and in the process gained access, surprising Corder as he entertained guests in the parlour.

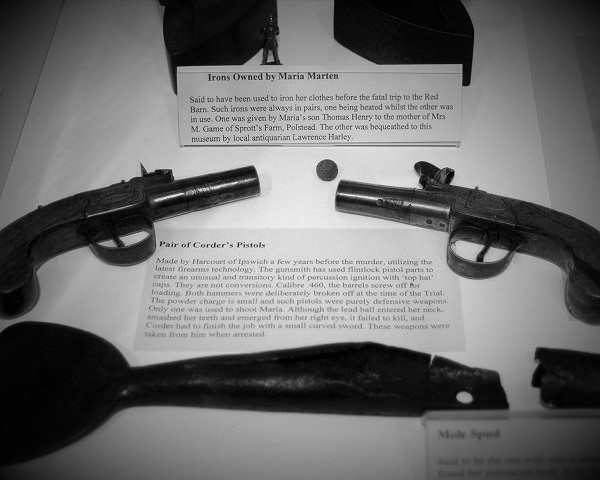

Denying all knowledge of both Maria and the crime, a search of the house uncovered some pistols bought on the day of the murder.

A passport from the French ambassador also suggested Corder was planning to flee to France, having caught wind of the discovery of Maria’s body from a friend’s letters.

Tried at Shire Hall in Suffolk, such was the public interest that admittance to the court was by ticket only and the judge and court officials had to push their way through the crowds.

The press had already decided on Corder’s guilt and congratulated the overwhelming public opinion that shared the same sentiment.

Indicted on nine charges to avoid any chance of a mistrial, Corder pleaded not guilty.

Ann Marten, Maria’s stepmother testified about her dreams, while Thomas Marten related the story of digging up his daughter’s body.

Maria’s little brother said he’d seen Corder with a pistol before Maria’s disappearance and later, walking from the barn with a pickaxe.

Suggesting that he never intended to marry Maria, the prosecution claimed that she had discovered Corder’s criminal past and had accused him of stealing money sent by her child’s father.

Admitting to being in the barn, Corder said they had argued and that he had then left her alone only to hear a pistol shot while he was walking away.

Running back to the barn, he said he found Maria dead with one of his pistols beside her.

Although he pleaded with the jury to give him the benefit of the doubt, it took them only 35 minutes to find him guilty.

After several meetings with the prison chaplain, Corder confessed to accidentally shooting Maria in the eye as she was changing out of the man’s clothing he suggested she wear as a disguise.

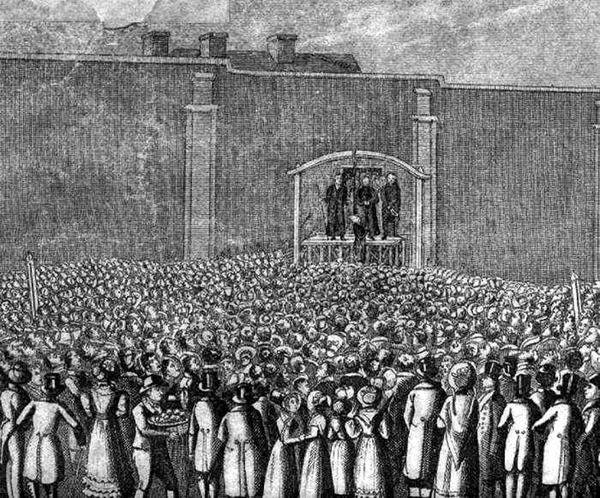

Estimates of the number of people in attendance at his execution ranged from 7,000 to 20,000.

Just before the hood went over his head, he confessed again:

Corder’s body was put on display in the courtroom with the abdomen cut open to reveal the muscles.

Over 5,000 people queued to see the gruesome sight.

Later, in front of an audience of students from Cambridge University, electric wires were attached to Corder’s body to demonstrate the contraction of muscles using electrical currents.

What must have gone through the minds of those students to see a dead body move?

How many wondered about the scientific possibility of ghosts communicating from the dead?

Here was a story that had all the elements to ignite the public’s imagination.

A poor girl murdered by a wicked squire; the supernatural communication with the dead; and Corder’s new life resulting from a lonely hearts advertisement.

19th-century fascination with the macabre knew no bounds.

Pieces of the rope used to hang Corder sold for a guinea each.

Part of Corder’s scalp with a shriveled ear still attached was displayed in a shop in London’s Oxford Street.

A lock of Maria’s hair sold for two guineas.

Polstead village became a tourist mecca with an estimated 200,000 visitors in 1828 alone.

Stripped for souvenirs, the Red Barn eventually burned down in 1842, but not before planks were removed from the sides, broken up, and sold as toothpicks.

The Victorian play “Maria Marten”, or “The Murder in the Red Barn” was a sensational hit throughout the mid 19th century and possibly the most performed play of the era.

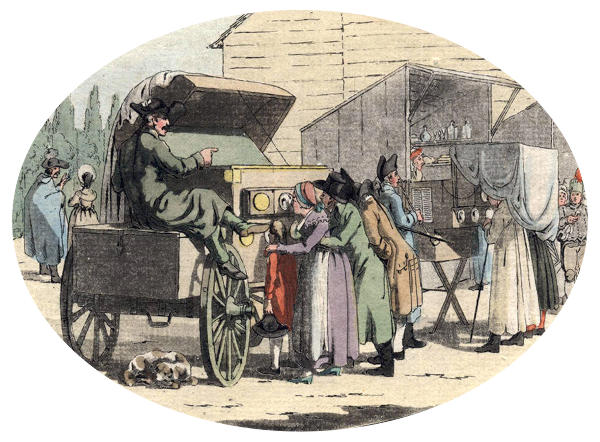

Even 19th-century fairground peep shows had to add extra apertures for viewers during shows of the murder.

Victorians portrayed Corder as a cold-blooded monster and Maria as the innocent victim, pure as the driven snow.

To suit Victorian sensibilities, her reputation and her children by other fathers was omitted, while Corder’s appearance deliberately aged to exaggerate his wickedness.

Doubts were raised about the veracity of Ann Marten’s dreams of Maria’s ghost.

How could she have known the exact location of Maria’s body unless the ghost really did appear … or the story was fabricated?

Ann was only one year older than Maria and rumours circulated of a possible affair between Ann and Corder.

Could Ann have been the murderer?

We’ll never know.

One thing is for certain—Maria’s ghost, whether dreamed or imagined, played a decisive role in the fate of William Corder and solving the Red Barn murder.