It was a cold, dark night as they crossed the moors on All Hallows’ Eve.

The folk at the village had said not to venture off the beaten path … but it was too late now.

“Look!” cried one of the travelers, pointing to a ghostly light on the horizon.

They stopped and stared in the direction of the light, mesmerized by two dancing figures that seemed to beckon them closer.

According to legend, travelers sometimes saw a strange light at night, especially over swamps, bogs, and marshes.

The light was said to hold power over people, drawing them closer, but, like a mirage, fading away as they approached.

Known as ignis fatuus in latin, meaning “foolish fire”, anyone who was lured off the trail by the light would surely lose his way.

The phenomenon became known by other names, most commonly will-o’-the-wisp, jack-o’-lantern, or friar’s lantern and was thought to be the devil’s work, the pranks of fairies, or even an omen of death.

The term will-o’-the-wisp dates from 1660’s England and means “Will-of-the-torch”, where “Will” was a given name and a “wisp” was a bundle of sticks or paper used as a torch for illumination.

Jack-o’-lantern has the same meaning, but using the name “Jack” and a lantern in place of a torch (wisp).

Jack-o’-lanterns were traditionally used to protect homes against the undead or to ward off evil spirits and vampires. It was also thought that the jack-o’-lantern’s light would identify a vampire and that they would then leave people alone.

Thought to have originated during the Dark Ages in Ireland, the custom of making jack-o’-lanterns involved carving out the middle portion of large turnips, rutabagas (swedes), or even potatoes.

Children would draw grotesque faces on them and set a candle inside, believing it to represent an old drunkard named Irish Jack.

In Irish folklore, there is a story of how Jack became intoxicated on All Hallows Eve. So close to death was he that the devil came to claim his soul. But he begged the Devil for one last drink. The Devil agreed but said Jack must pay. Jack had no money and asked the Devil to change into the shape of sixpence so that he could pay. The Devil could change into any shape he wanted, and so agreed. But instead of paying, Jack put the sixpence next to a cross he kept in his pocket, entrapping the Devil. Now Jack could bargain for his soul and made the Devil promise never to come after him again. The Devil agreed and let Jack live.

For a while, Jack reformed his ways, attending church and giving to the poor instead of squandering his money on drink. But he soon fell back into his old ways. When death finally came knocking, the Devil kept his promise not to take his soul. But neither was Jack’s soul worthy of a place in heaven. So the Devil tossed him a burning coal from hell, which Jack placed inside a carved-out turnip to use as a lantern while he wandered the earth—a tortured soul looking for a place to rest.

In Celtic-speaking regions, the Gaelic festival Samhain “Summer’s End” was a time when people believed supernatural beings and the souls of the dead roamed the earth—just like Irish Jack.

Samhain became Halloween, and even today, most Jack-o’-lanterns share a frightening, tormented expression and we leave them in a prominent position to ward off evil spirits.

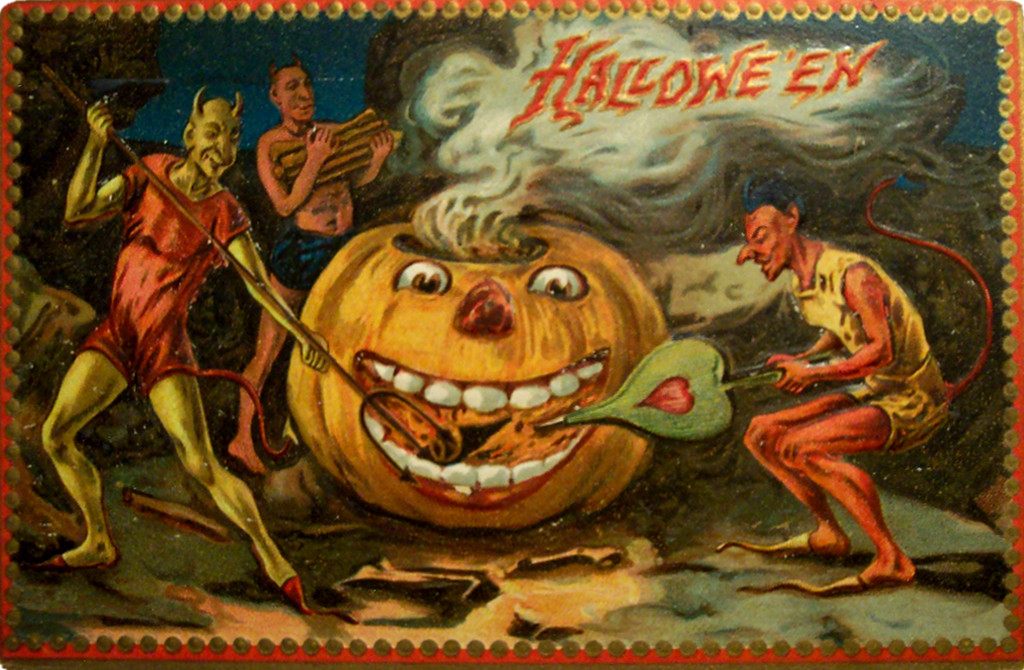

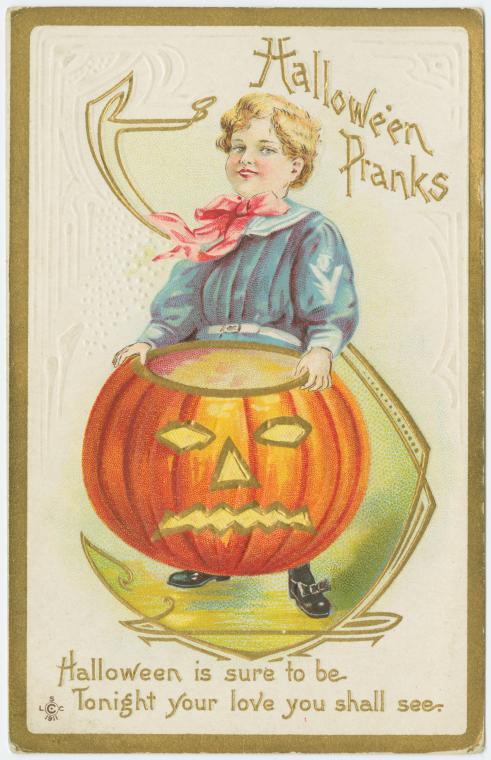

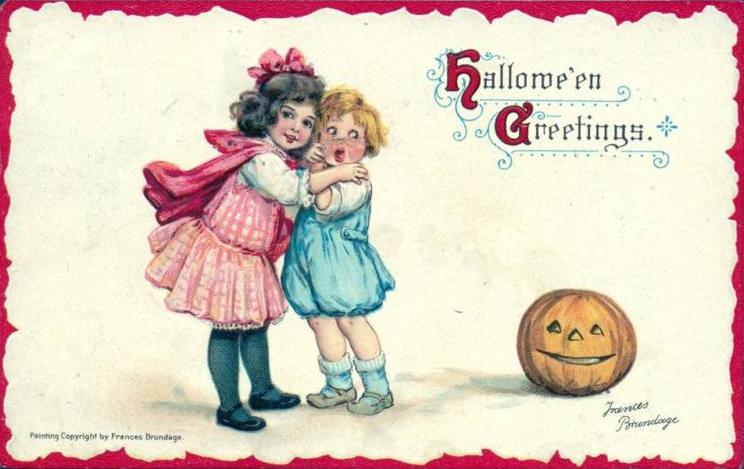

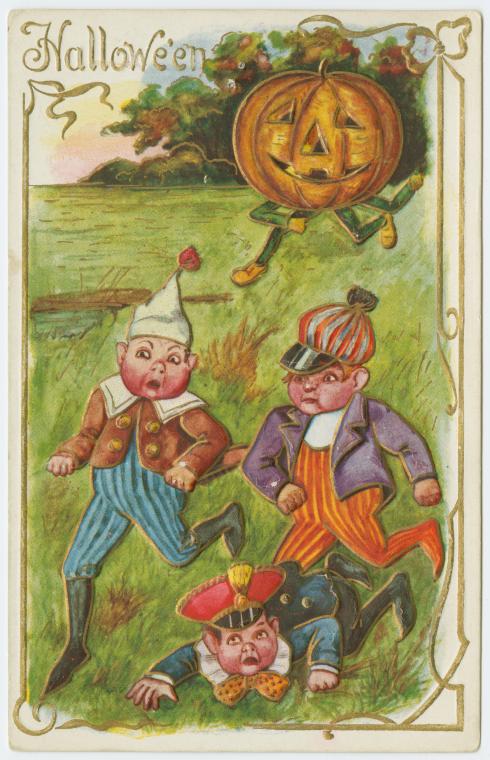

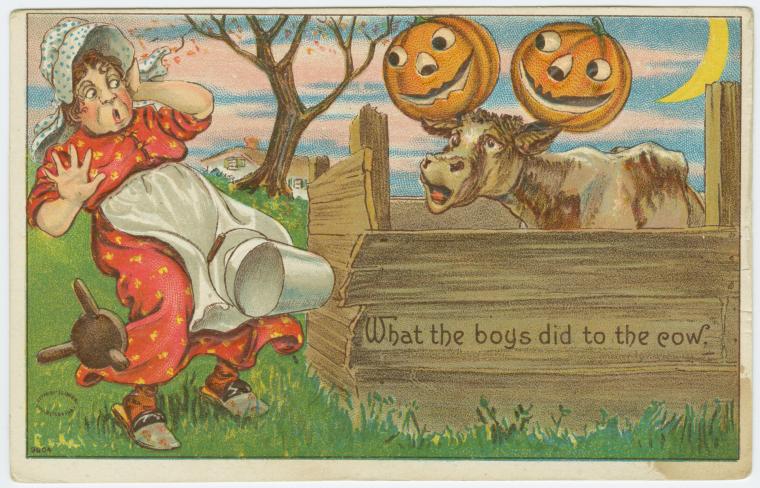

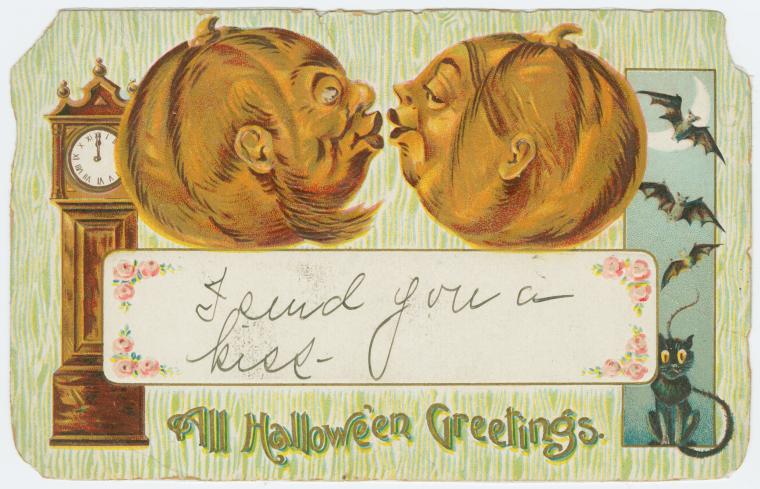

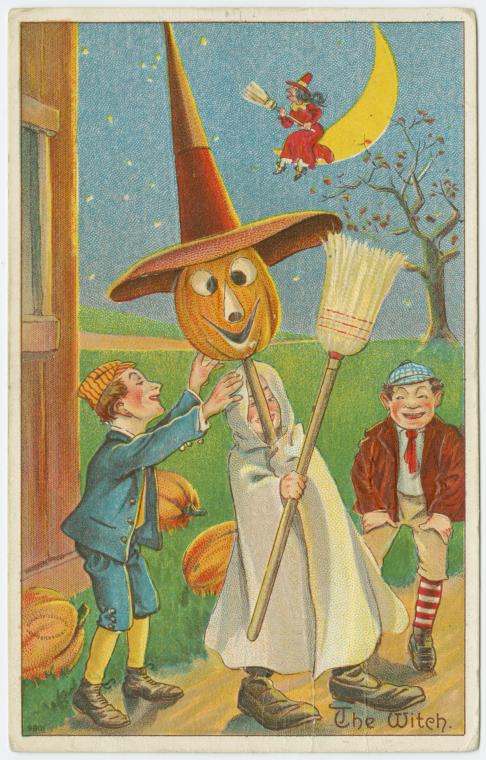

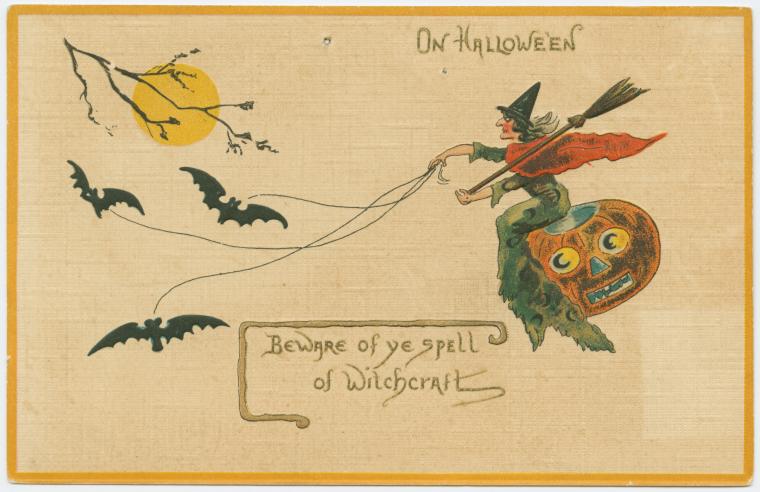

Jack-o’-lanterns have featured prominently in the Halloween celebration through the centuries, as shown by these delightful Victorian and Edwardian Halloween postcards.

Happy Halloween!

References:

Wikipedia.

Halloween, Hallowed is Thy Name: How to Scripturally and Theologically Justify Christian Halloween Haunted Houses and Other Evangelistic Events for Christian Fellowship, Fun, and Prophet by Rev. Dr. Eddie J. Smith.