Following on from our article on corsets, we turn our attention to the bustle.

We think the bustle epitomizes Victorian fashion during the last quarter of the 19th century. It’s particularly synonymous with the period of peace, prosperity, and progress known as the Belle Époque.

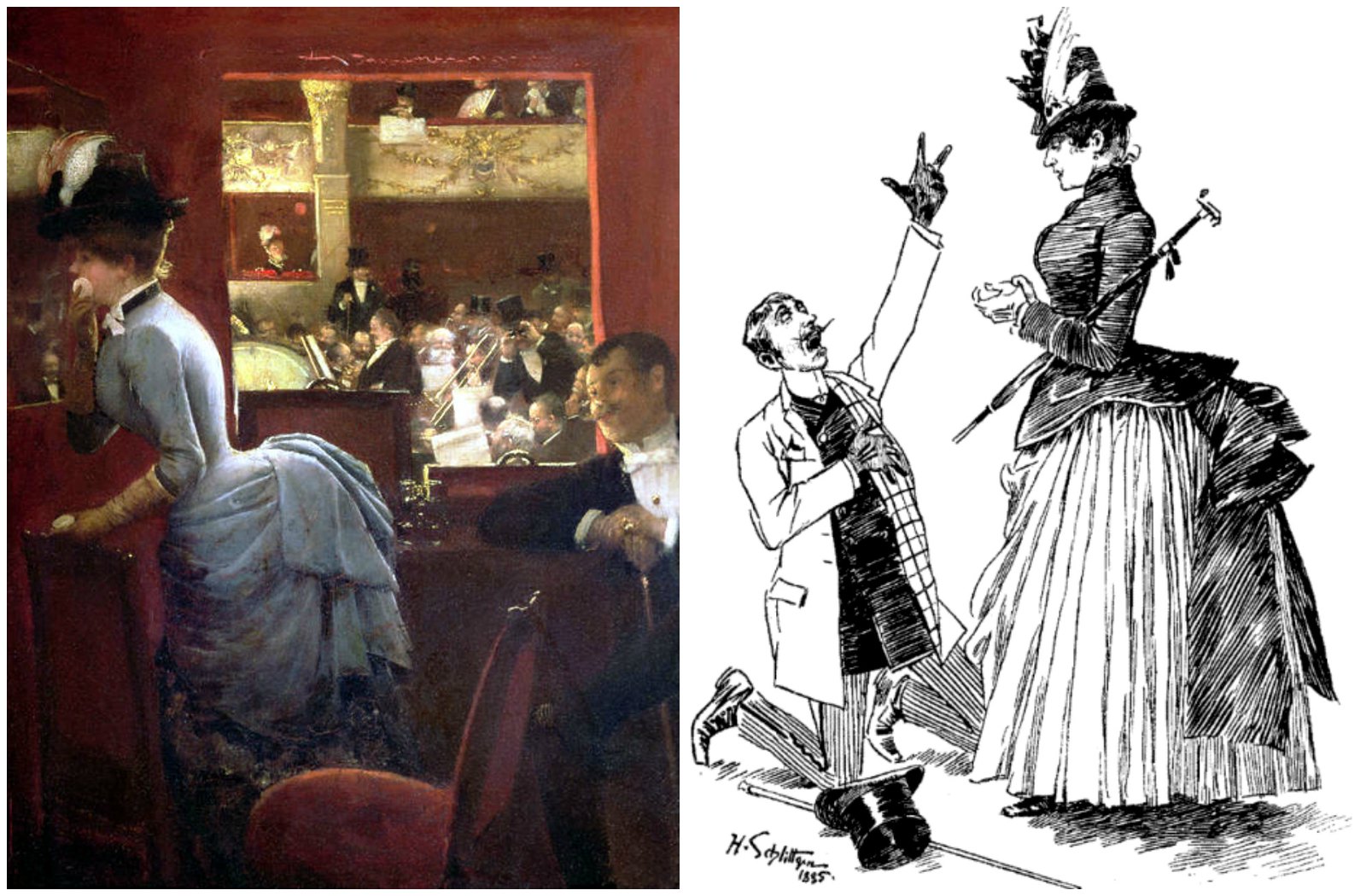

The bustle was celebrated in paintings by the Belle Époque artist Jean Béraud, by the fashion portraitist James Tissot, and by the pointillist artist Georges Seurat in his iconic work “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte”.

Out went the huge crinolines of the 1860’s …

… and in came a slimline version.

The bustle was far more convenient for day-to-day activities … although some compromises were still necessary as Jean Béraud illustrates so aptly in his painting “Woman in Prayer”.

And the effect it had on men ranged from admiring looks at the opera, to marriage proposals on bended knee.

Even today, the essence of the bustle has been used by top designers such as Vera Wang in her stunning wedding dresses.

Crinolines and bustles were types of framework to give fullness to dresses and keep them from dragging.

Heavy fabric would weigh down the skirts of dresses and flatten them, causing a woman’s petticoated dress to lose its shape during everyday wear—merely from sitting down or moving about.

From around the 1870s to the late 1890s, the large bell-shaped crinolines were superseded by the bustle as the preferred way to create the desired fullness that was in vogue.

The overskirt of the late 1860s was now swept up toward the back with the bustle providing the needed support for the new draped shape.

This fullness was drawn up in ties for walking that created a fashionable “puff”.

In this painting from Belle Époque-era Paris, we see ladies crossing the street in rainy weather while holding their skirts up with one hand.

The bustle made it much easier to manage the fullness of skirts and keep them from dragging on muddy streets.

Supporting this trendsetting puff was a variety of things such as horsehair, metal hoops and down.

More sophisticated designs would allow bustles to reach their maximum potential—looking like a full shelf at the back. Some even joked that the bustles could support an entire tea service!

Some of the sculptural undergarments required to achieve the extreme bustle of the 1880s are shown here.

To support the heavier gowns, light and flexible frameworks were created using wire, cane, and whalebone, held together with canvas tapes or inserts inside of quilted channels.

The feminine bustle silhouette continued through the 1890’s before making way for the S-curve silhouette of the Edwardian era.

Sources

Metropolitan Museum of Art

wisconsinhistory.org

Corsets and Crinolines by Norah Waugh