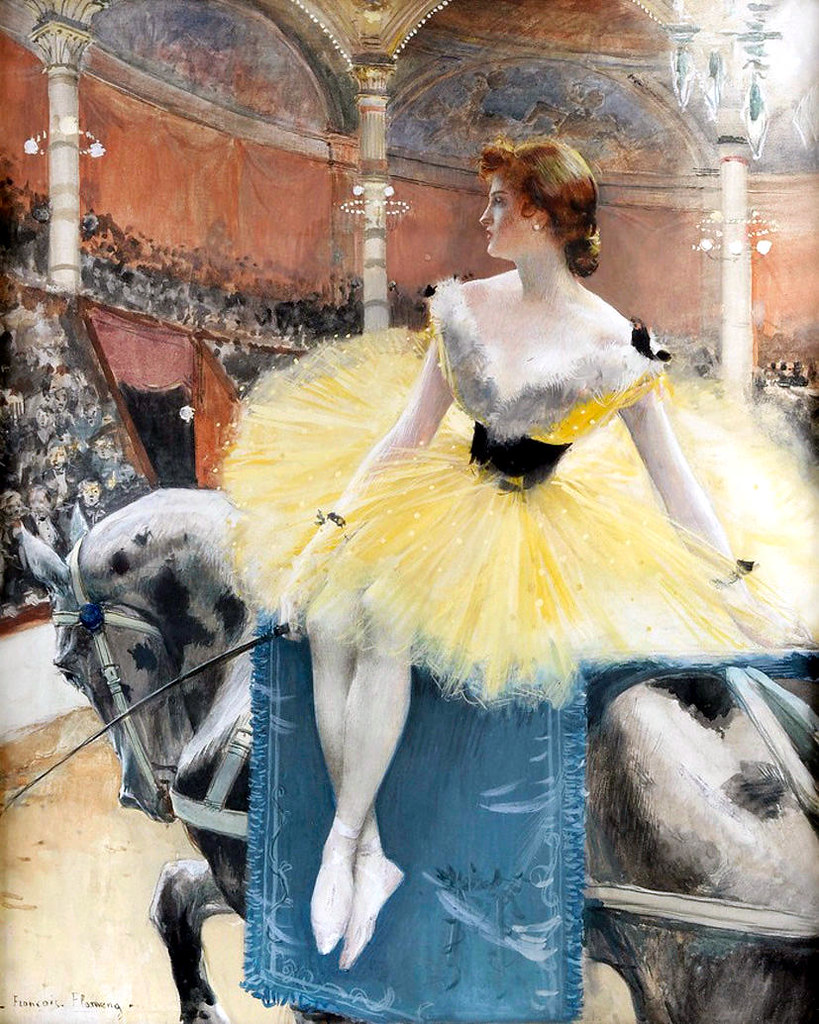

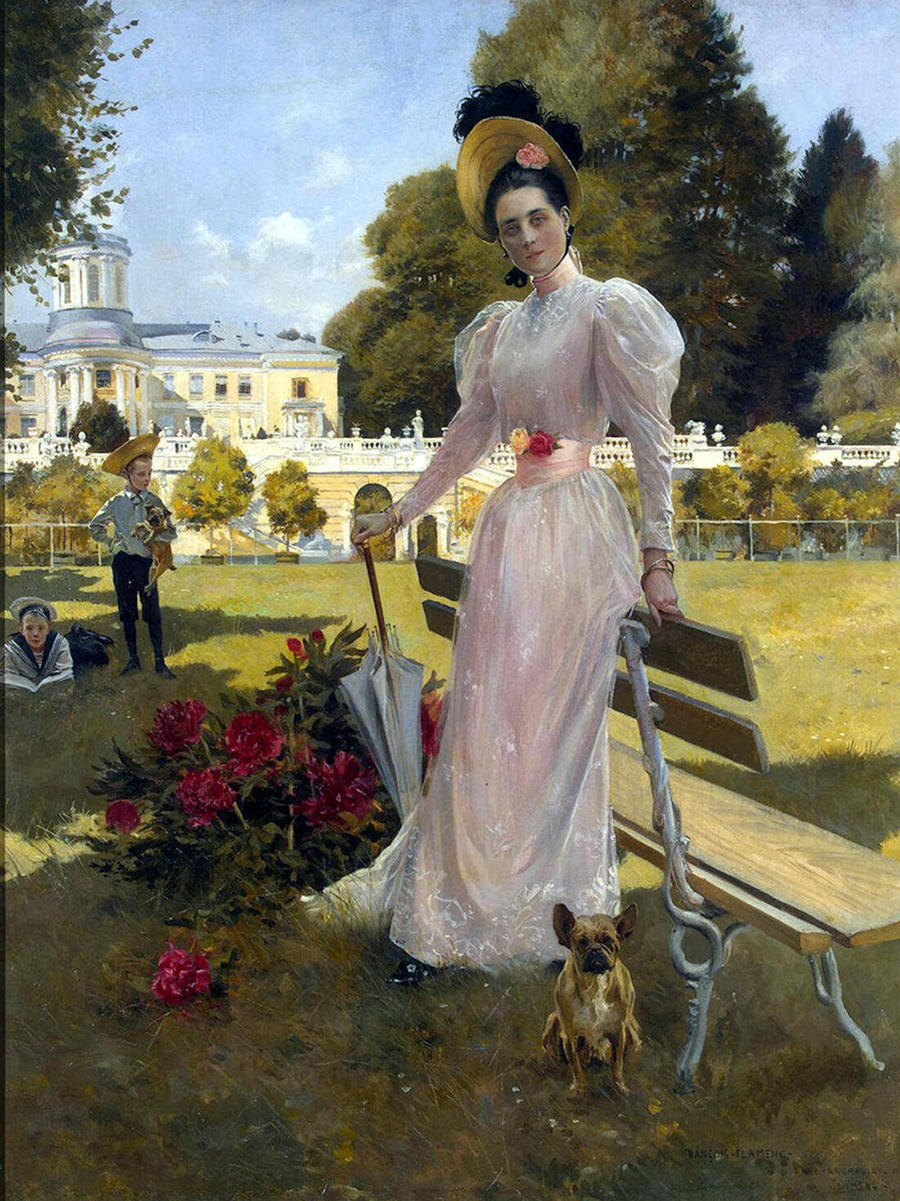

Beautiful places, beautiful people, beautiful clothes—Francois Flameng loved to paint them all.

Born in an art studio in Paris in 1856, Flameng may have known from an early age that he was destined to be an artist.

Indeed, in many ways, he had everything going for him.

Paris was the center of the art world and his father was a celebrated engraver who had once wished to be a painter.

All of his father’s regrets were channeled into making his son a success.

Specializing in history painting and portraiture, Francois Flameng became a professor at the Académie des Beaux-Arts—the premier institution of fine art in France.

If you’d like to add a little atmosphere as we view a gallery of Flameng’s work, press play.

Many of his studies in Italy are rich in architectural detail in the most vivid light and color.

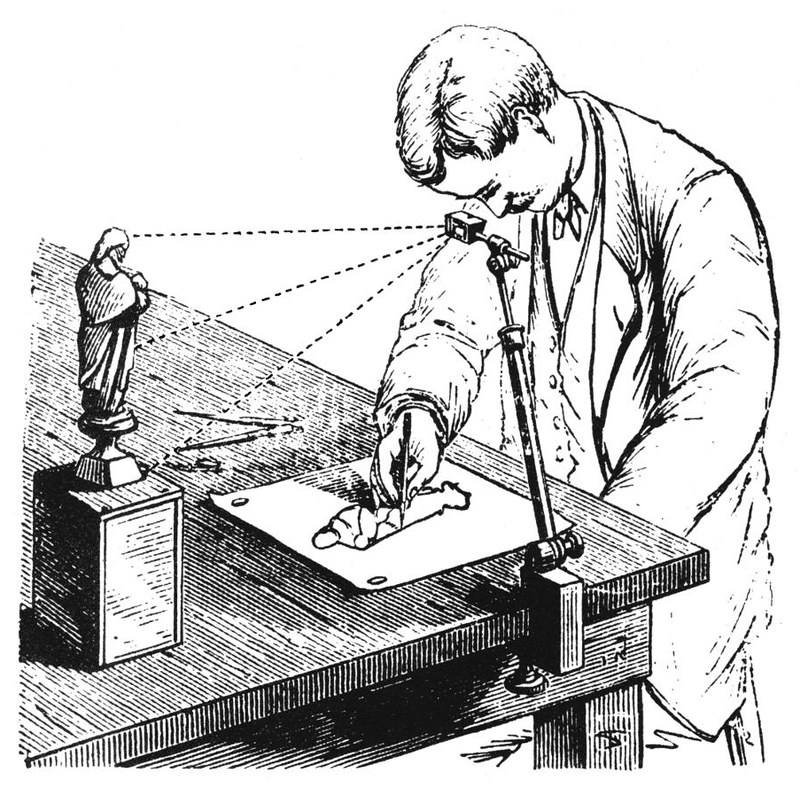

Flameng would often use a camera lucida to create an optical superimposition of his subject.

Allowing him to duplicate key points of the scene on the drawing surface, it would aid in the accurate rendering of perspective.

Once he had the sketch to ensure proportion and perspective were correct, he would paint rapidly yet with such fine detail that within an hour he had what took most artists four hours to complete.

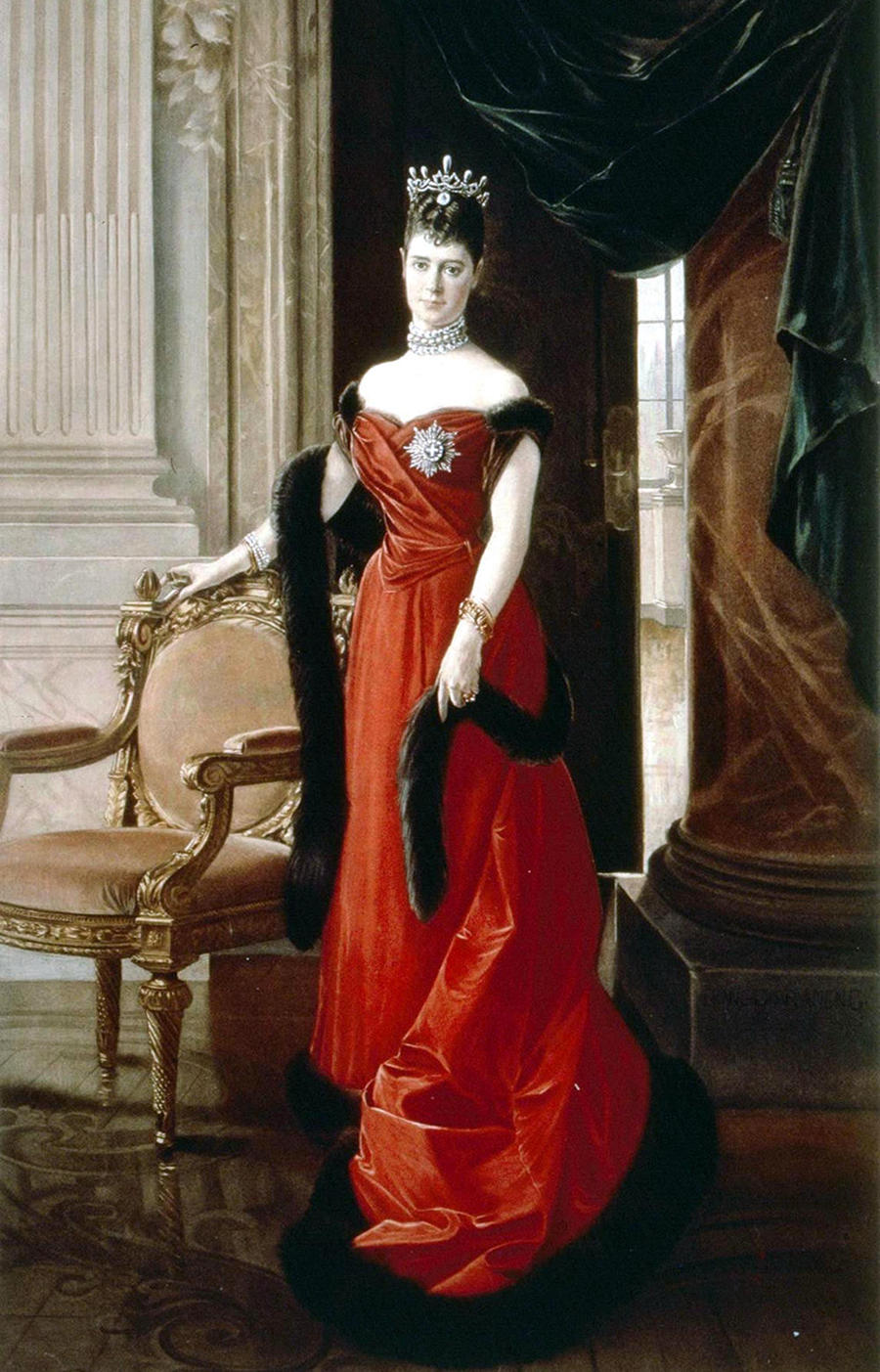

Flameng said that fashions and hairstyles changed so often that the exact likeness captured in a portrait was gone within a few short years.

Therefore, he said, portraits should aim to be pleasant works of art that one would purchase to adorn the wall of a drawing room, even if it were not a portrait of one’s own image.

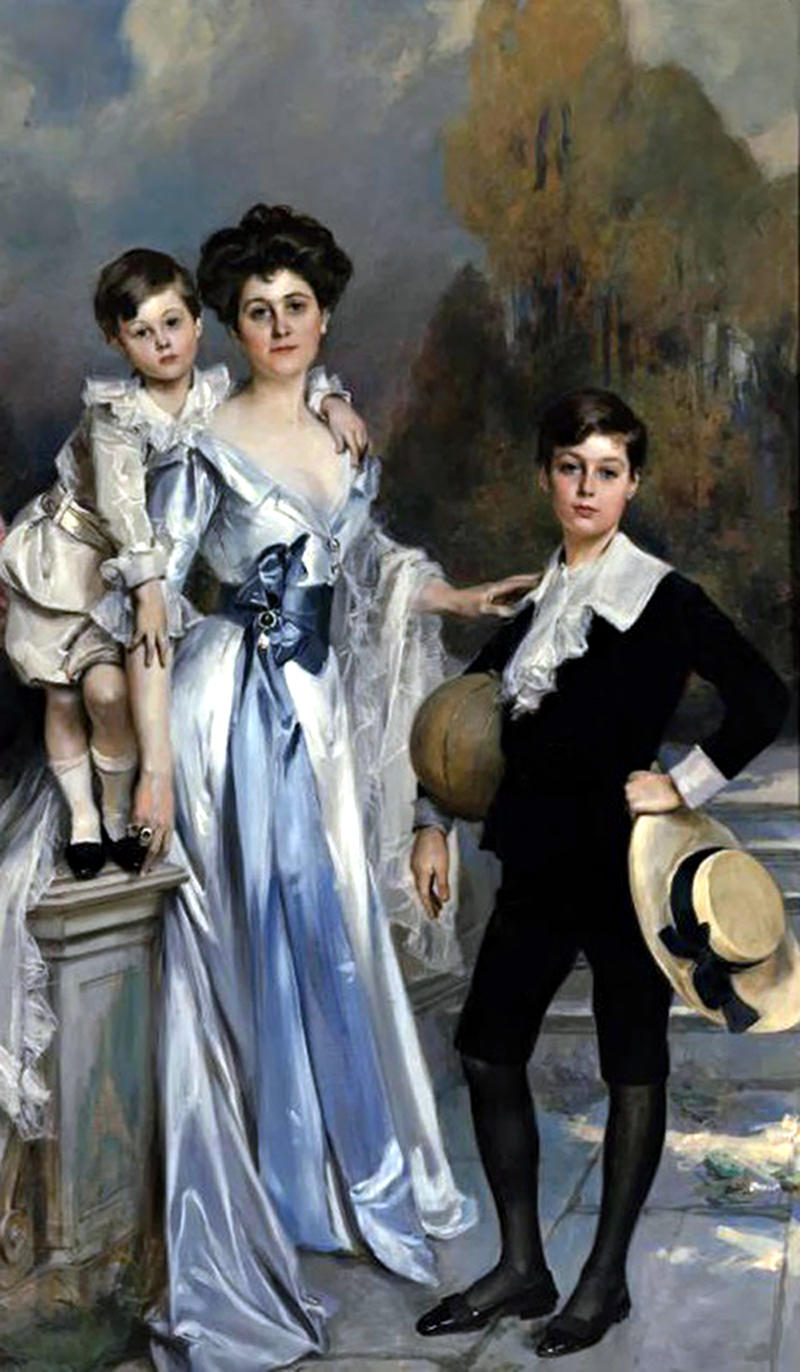

Flameng found that he learned as much about the social aspects of his work as he did the actual practicing of his art.

Making sittings more agreeable for models he had to learn their tastes and habits, likes and dislikes.

That way, he could encourage them to pose in ways that reflected their personality and remain in one position for a long time without noticing it as much.

Of equal importance to remaining true to his artistic integrity was producing a work that was pleasing to the subject and also to her friends and acquaintances.

When subjects disagreed with his choice of arrangement or style of composition, he would use all his skill to gradually encourage her to see his point of view without contradicting or offending, always admitting she was right, but gently helping her drop her own preconceived mental image.

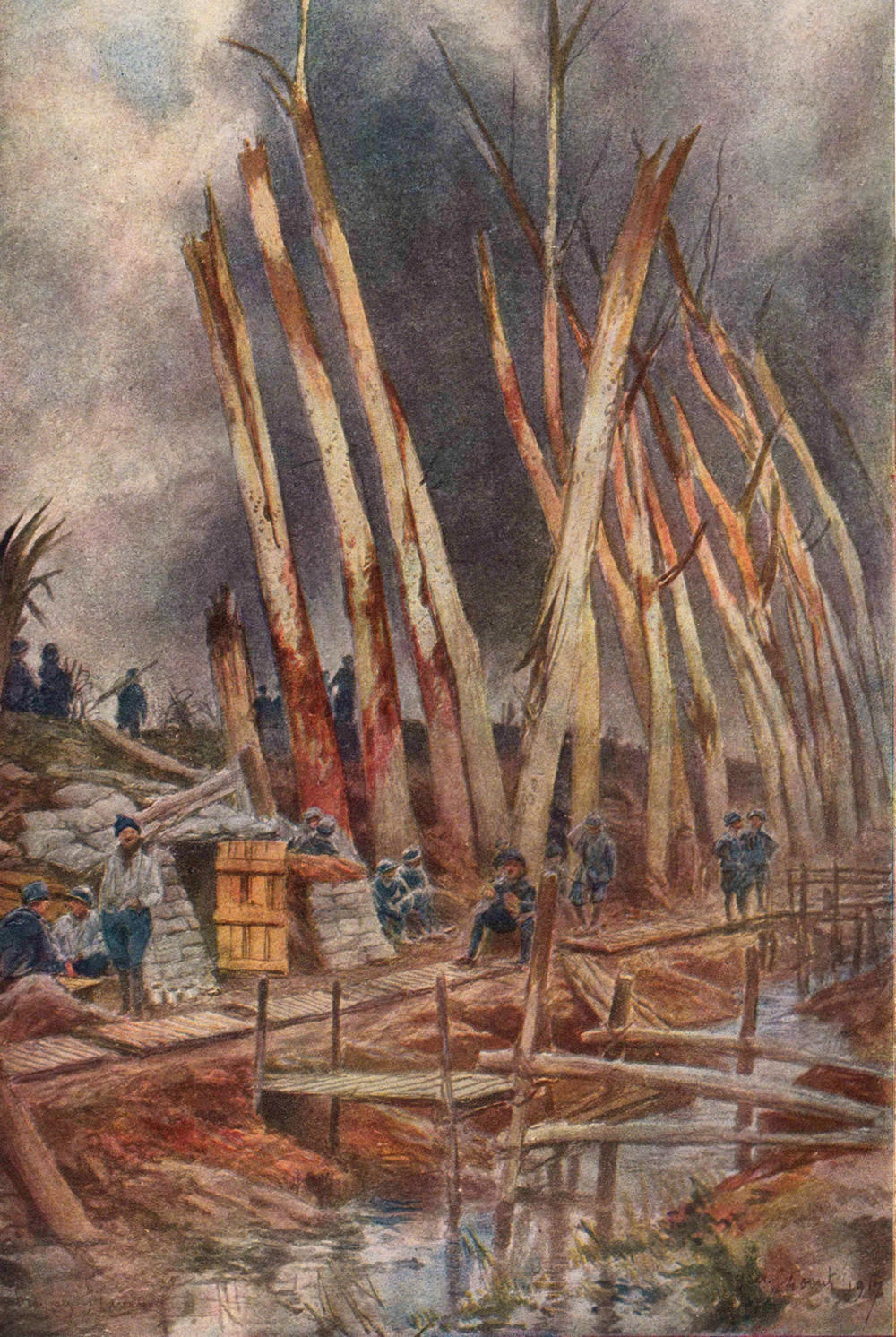

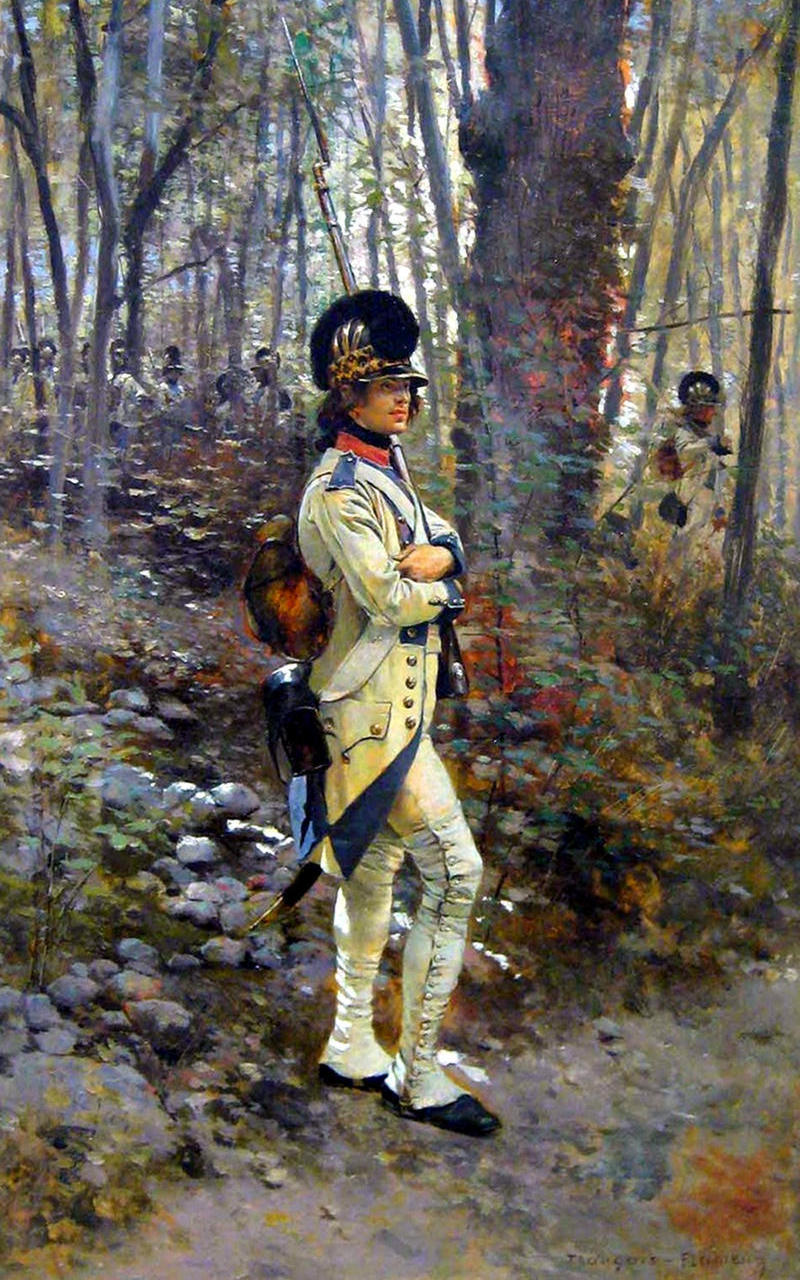

Flameng painted the colors and pageantry of war.

But he was no stranger to its violence.

At age 14, he was playing with fellow students at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, when a bombshell exploded in the courtyard.

It was a gift from the Prussians to mark the onset of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, and it prompted him to enlist.

Accepted in the ambulance corps, when Paris fell to the Prussians, he saw seven children killed under the window of his father’s house in Montparnasse.

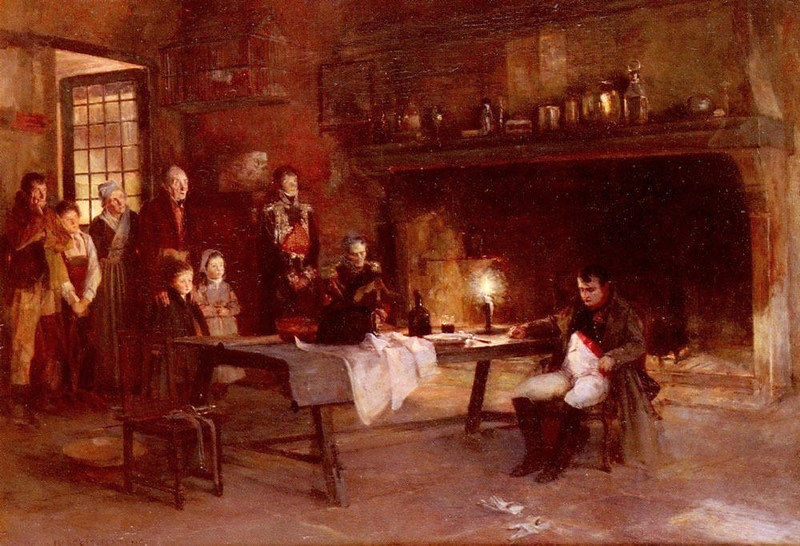

Francois Flameng didn’t only paint beauty.

Renowned for his paintings that showed some of the horrors of the First World War, he was an accredited documenter for the War Ministry and named honorary president of the Society of Military Painters.

Flameng’s war paintings were derided by many critics for being too realistic and not including heroic drama.