Rising majestically above the trees, deep in the center of the Netherlands, the towers of Castle de Haar glisten in the morning sunlight.

This is no ordinary castle.

It is the largest in the Netherlands, and one of the most luxurious in Europe.

From Humble Beginnings

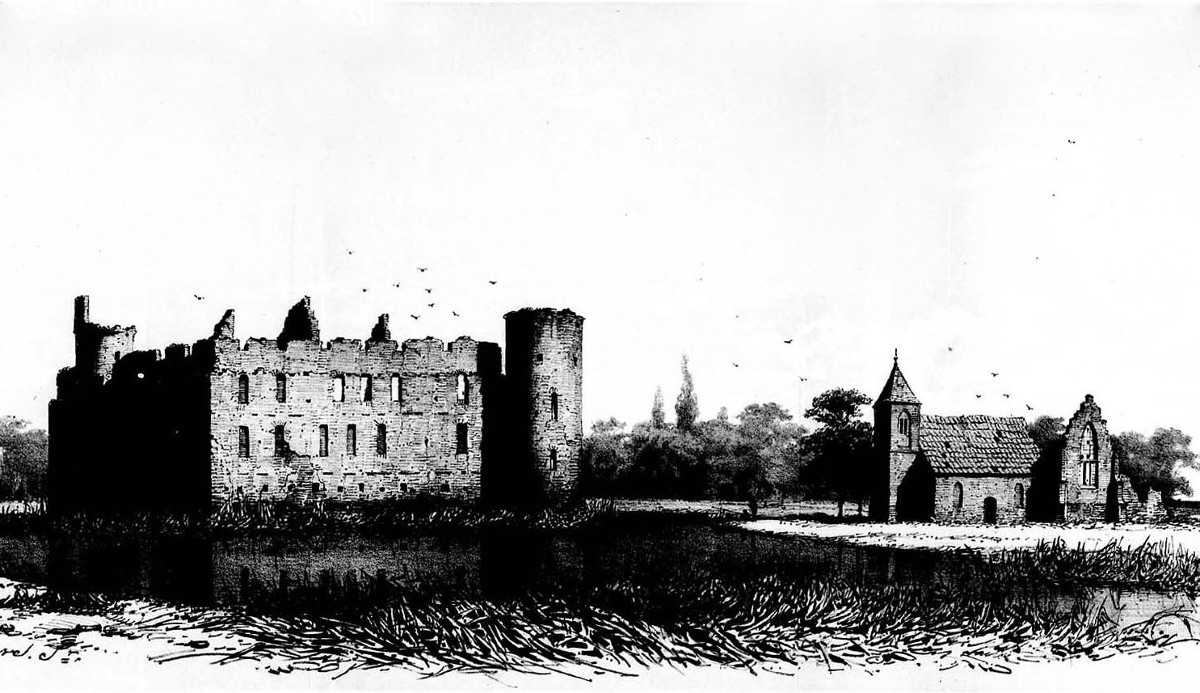

To go from this, in 1892 …

… to this, in 1912 …

… required big money. Rothschild money.

In 1391, the family De Haar was granted rights to the original castle and surrounding lands that existed on the same site as the current castle.

Changing hands to the Van Zuylen family in 1440, then burned down and rebuilt in the early 1500s, the castle had fallen into ruins by the late 17th century.

Eventually, De Haar was inherited by Etienne Gustave Frédéric Baron van Zuylen van Nyevelt van de Haar.

Try saying that with a mouthful of Edam.

Etienne married Baroness Hélène de Rothschild in 1887—and the money connection was forged.

Restoration on a Grand Scale

20-years of restoration has created one of the world’s most beautiful and romantic castles.

Fully financed by Hélène’s family, the Rothschilds, the famous Dutch architect Pierre Cuypers set about building 200 rooms and 30 bathrooms.

Well, you never know when you’ve got to go, do you?

Installing all the mod-cons of the late Victorian and Edwardian Eras, the castle had electrical lighting running off its own generator and steam-based central heating.

A large collection of copper pots and pans adorns the kitchen that was very modern for its day, having a 20 ft-long furnace heated with either coal or peat.

Decorated with fine detail throughout, the kitchen tiles have the coat of arms of both the De Haar and Van Zuylen families.

Richly ornamented woodcarving reminiscent of a Roman Catholic church adorns the interior along with old Flemish tapestries and paintings.

Formal Gardens

Reminiscent of the French gardens of Versailles, the surrounding park contains many waterworks and 7000 trees.

Elf Fantasy Fair

Attracting some 22,500 visitors every year, the Elf Fantasy Fair held in April at Castle de Haar is the largest fantasy event in Europe.

Next to fantasy, there are also themes from science fiction, gothic, manga, cosplay and historical reenactment genres.