Victorians were avid readers.

Just as we bury our faces in our mobile devices on the morning commute, so too did Victorians with the latest penny fiction.

The increased literacy rate from schooling, cheaper production, and broader availability of books through libraries all benefited reading.

Towards the latter half of the 19th century, gas and electric lighting also meant that reading after dark didn’t have to be by candlelight or messy oil lamps.

Novels were often serialized in monthly parts, making them more easily accessible and shared. Weekly or monthly segments often ended on a “cliff-hanger” to keep readers hooked and anticipating the next installment.

Perhaps the best know serialized novels were the “Penny Dreadfuls”. Costing just one old penny, they focused on the exploits of detectives, criminals, or supernatural entities.

The price of new books—often only available as a set of three—was out of reach for most working class people, so they borrowed from circulating libraries such as Mudie’s (founded 1842), which dispatched books all over Britain for a modest subscription fee.

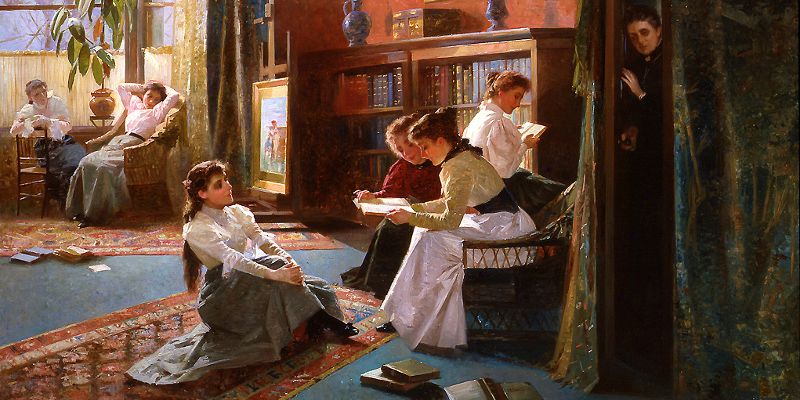

For the wealthier classes who could afford first editions, reading from their own collection would be an everyday occurrence.

Six months after the original publication, books became cheaper, being issued as single volumes. And the growth of the rail network helped make novels cheaper still at railway stations.

There would always be something new to read for a long journey.

Fiction was thought to hold influential power over readers. George Eliot wrote that people are,

The 18th-century view that reading contemporary novels was a time-wasting leisure activity gave way to 19th-century ideals on their ability to educate.

Victorians believed that although novels lacked the cultural seriousness of classical texts, they did nevertheless bring awareness of historical periods and places that might help bring about social reform and develop Christian moral values.

By the mid-1800’s, the most widely read novel in England was the anti-slavery Uncle Toms Cabin of 1852 by American Harriet Beecher Stowe.

But if novels could influence for the good, they could also influence for the bad.

Novels were thought to corrupt the working classes by giving them ideas above their station or encouraging them to emulate the life of fictional criminals.

Cultural opinion leaders were particularly concerned about fiction’s effect on women. They argued that women were more susceptible to excitement and often over-identified with characters in novels that could make them more dissatisfied with their lives.

Thank goodness the novelists themselves started to push back against the disillusioned ideology of the critics. They assumed readers could make up their own minds and did not need protecting. George Eliot, Thomas Hardy, George Gissing, and George Moore trusted their readers’ sense of responsibility.

By the late 19th century, novels had become a pleasurable pastime with the freedom to read anywhere.