Libraries have been around since antiquity. Their emergence marks the end of prehistory and the dawn of history.

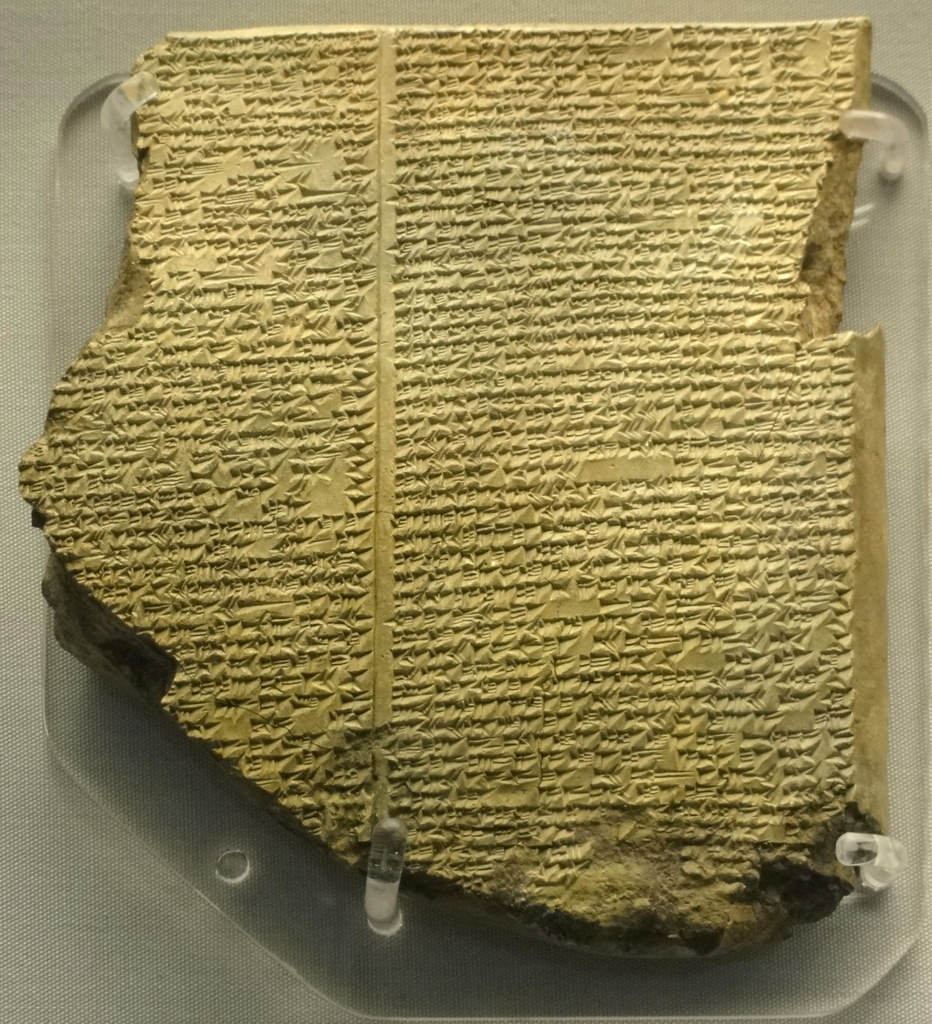

The Sumerians stored records of commercial transactions and inventories in Cuneiform script on clay tablets, some dating as far back as 2600 BCE.

Over 30,000 tablets were found in Nineveh, the ancient capital of Assyria, containing stories about creation, and omens about the moon and sun. And we thought tablets were a relatively recent innovation!

Written books first appeared in Classical Greece in the 5th century BCE. By the end of the 6th century BCE, the great libraries of the world were in Alexandria, Egypt, and Constantinople, the capital city of the Byzantine Empire.

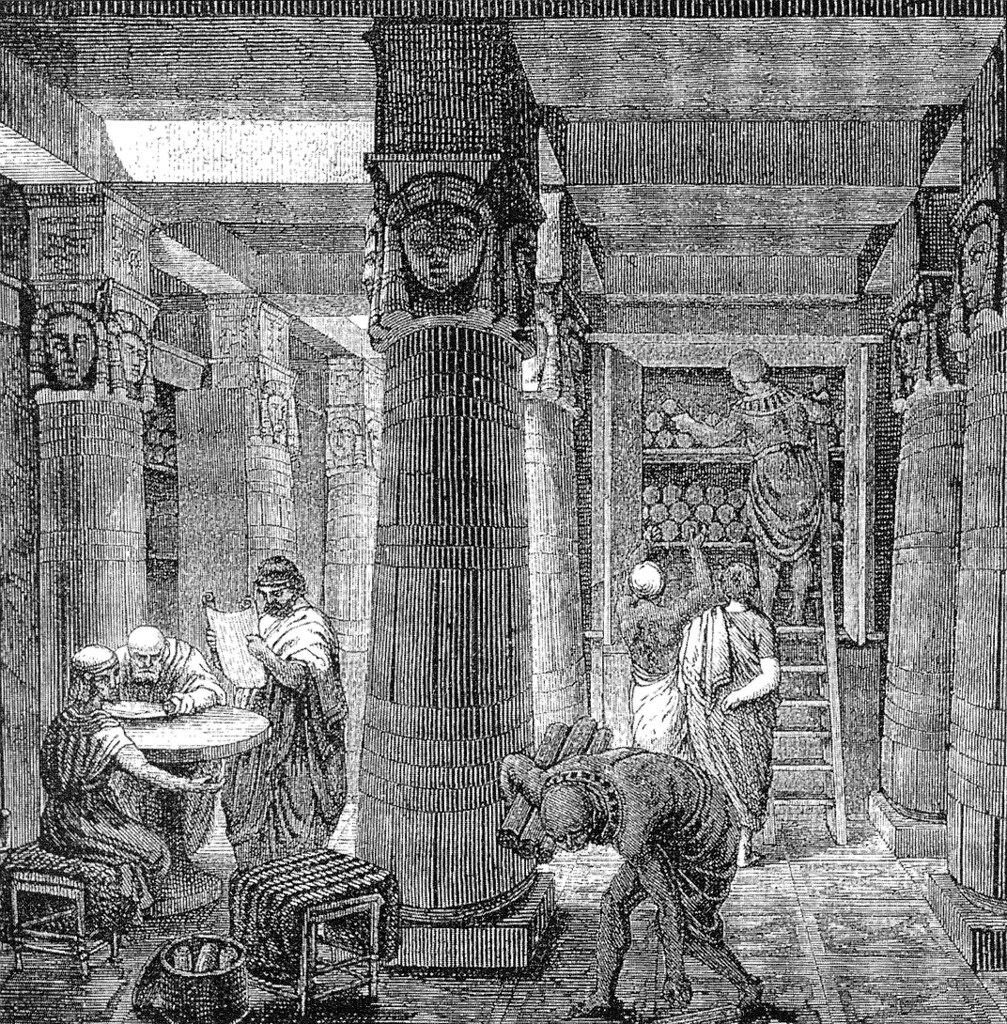

While most Greek libraries were private, the Romans built public libraries, with successive emperors striving to outshine their forebears.

Gaius Asinius Pollio, lieutenant under Julius Caesar, built the first public library in Rome—the Anla Libertatis. Works of Greek and Latin were kept separately, and he adorned it with statues of the most celebrated heroes.

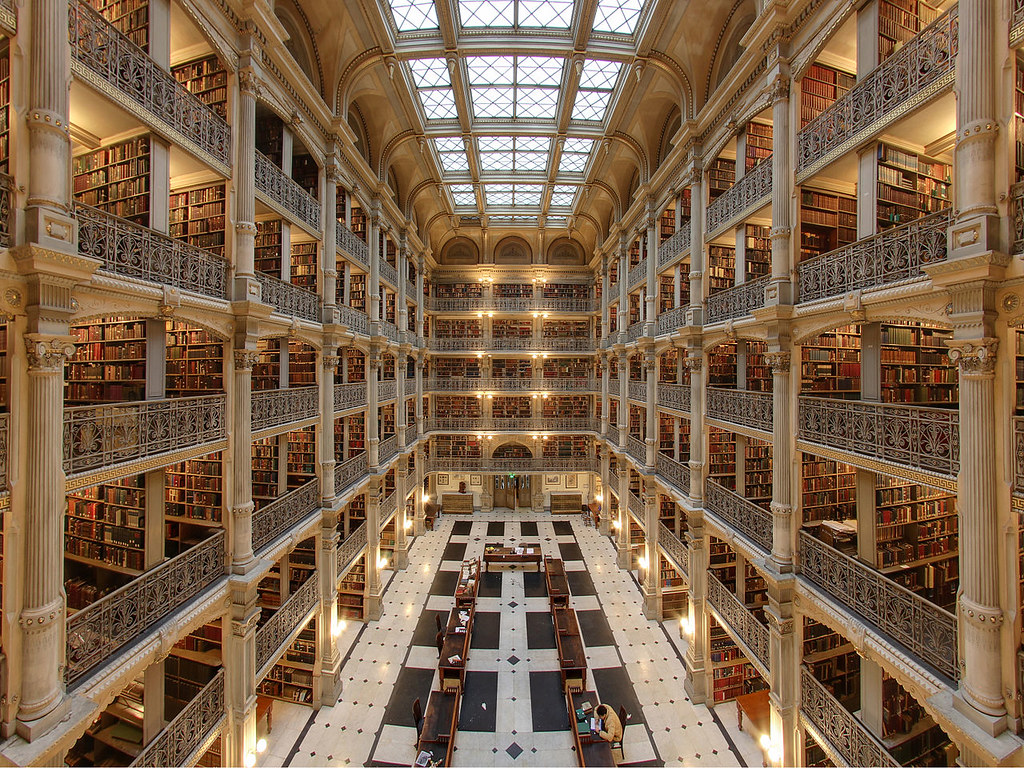

Emperors Augustus, Tiberius, Vespasian, and Trajan would build more libraries along the same lines. Trajan’s Ulpian Library was 50 ft high, reaching to 70 ft at the peak.

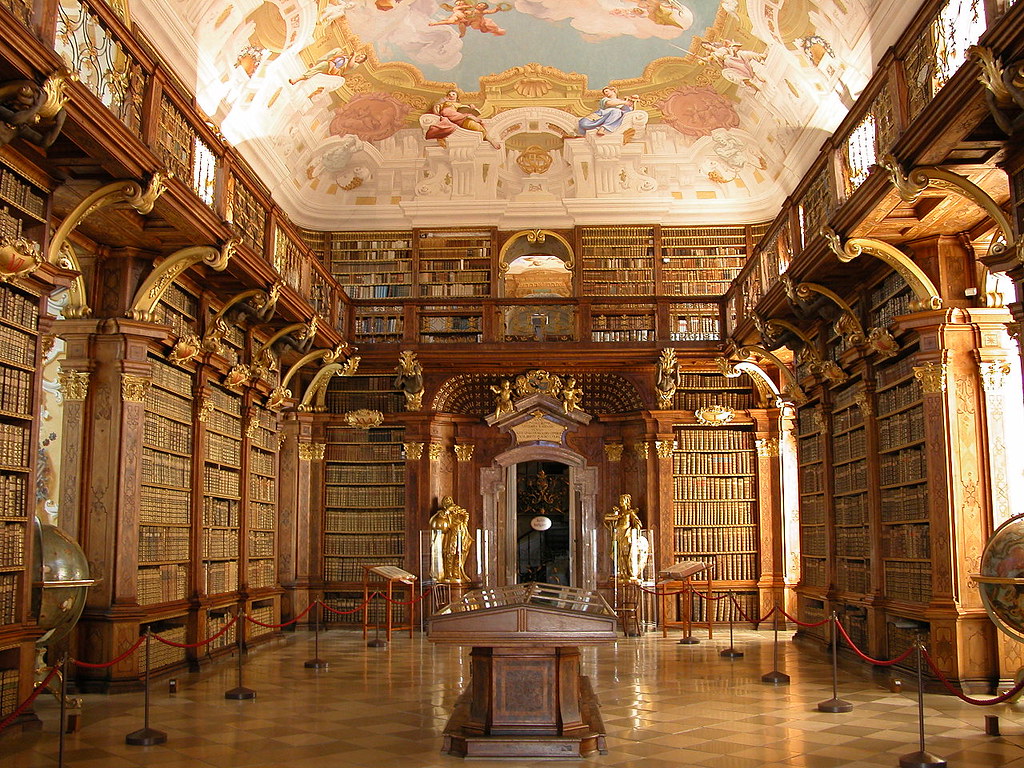

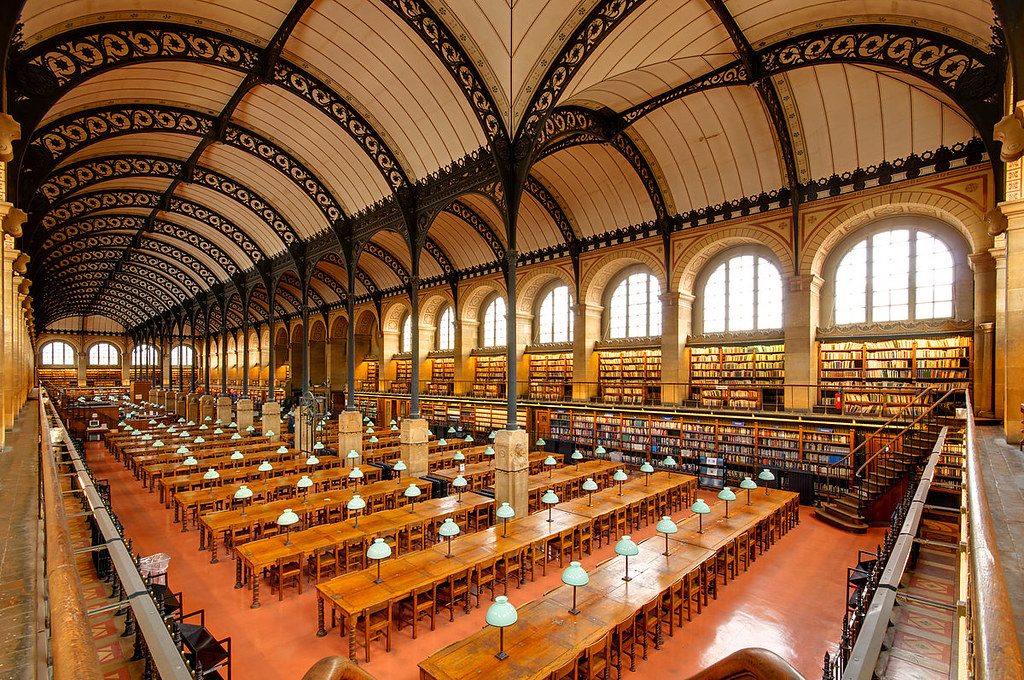

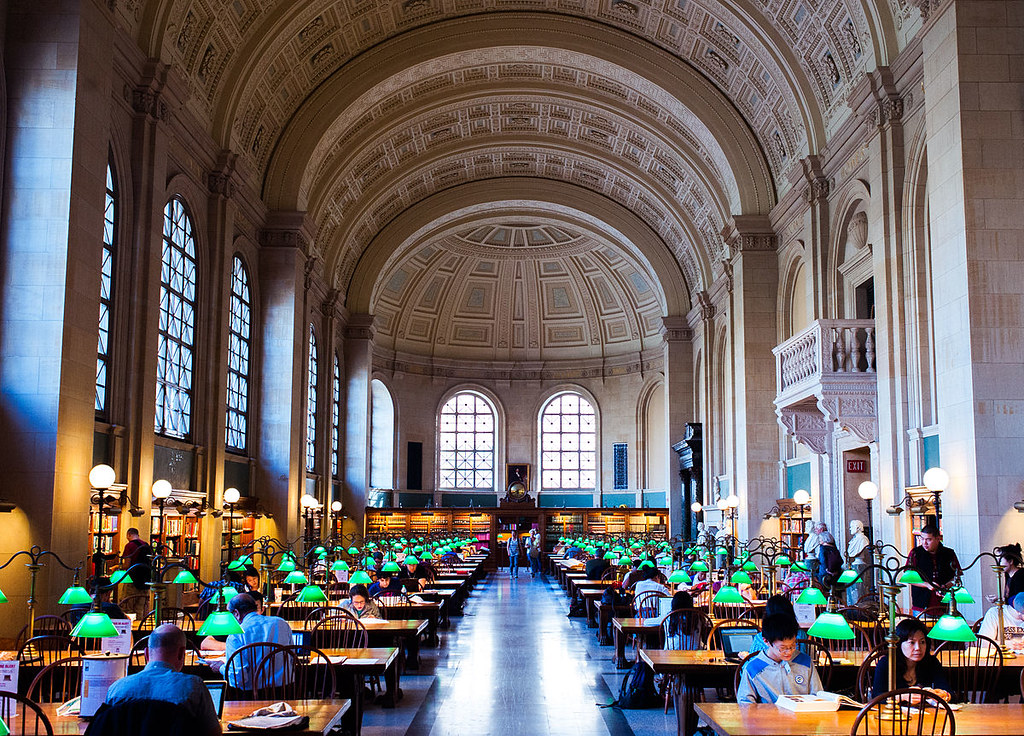

And so began a tradition of building libraries as grand monuments to learning.

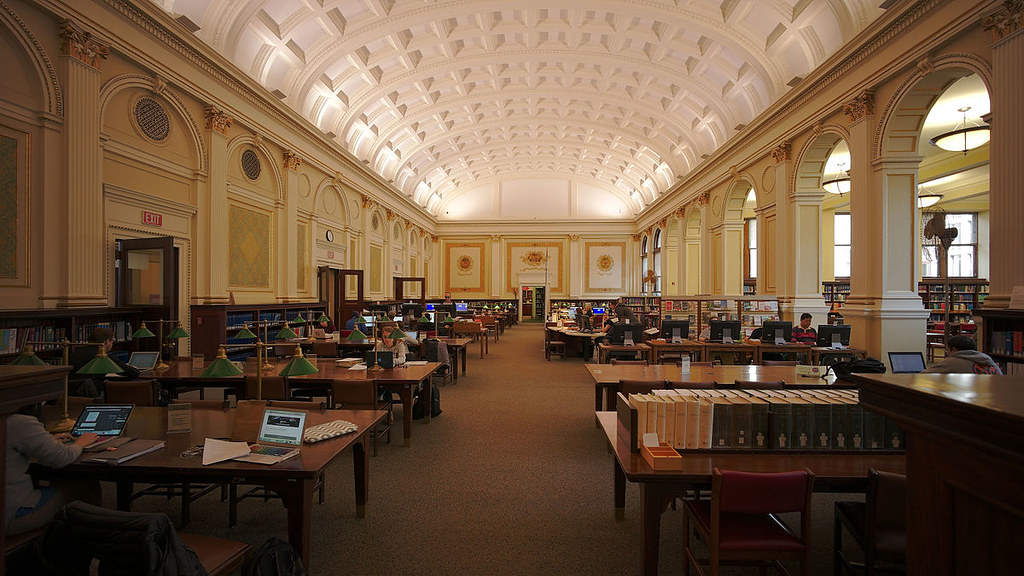

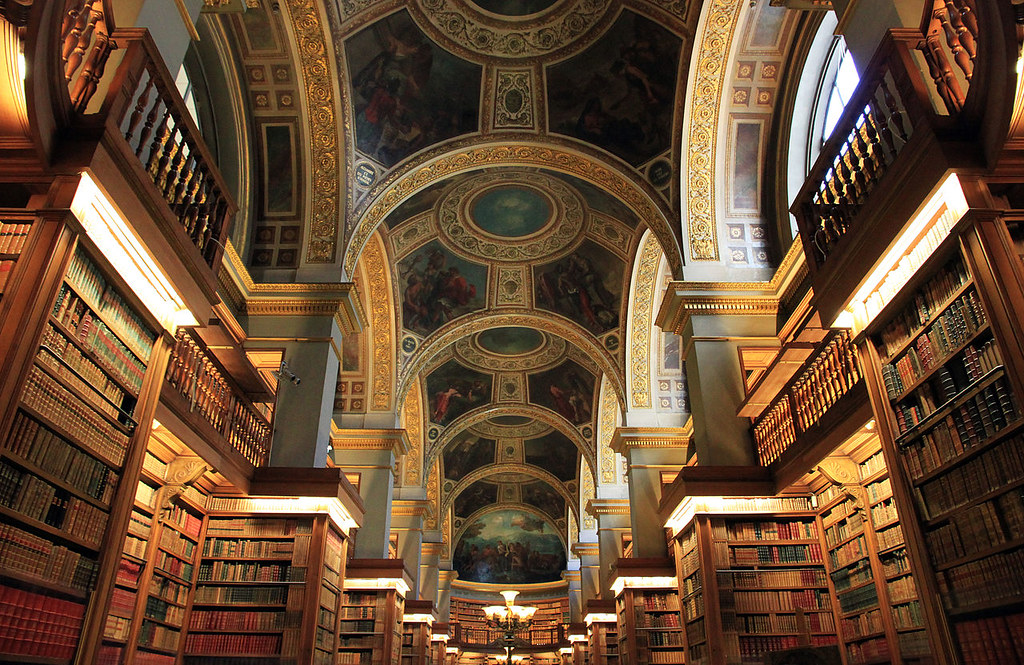

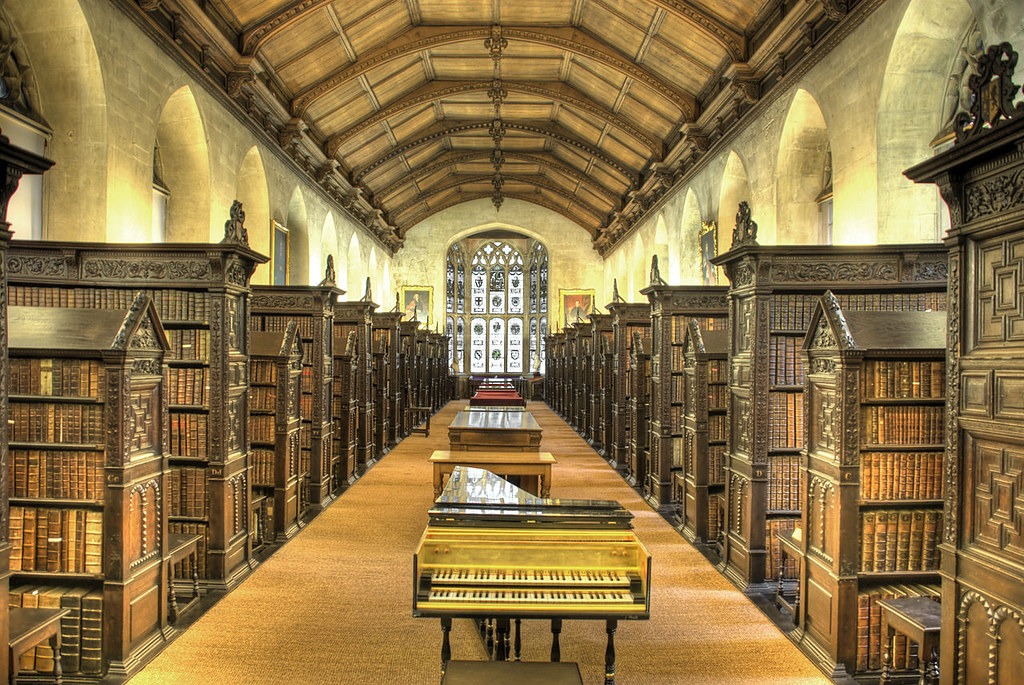

Many libraries are beautiful works of art in and of themselves.

Join us as we travel inside some of the world’s greatest libraries.

“Is there anything so delicious as the first exploration of a great library – alone – unwatched?”

—Richard Jefferies.

“Perhaps no place in any community is so totally democratic as the town library. The only entrance requirement is interest.”

—Lady Bird Johnson.

“If you have a garden and a library, you have everything you need.”

—Marcus Tullius Cicero.

“I go into my library and all history unrolls before me.”

—Alexander Smith.

“A library is not a luxury but one of the necessities of life.”

—Henry Ward Beecher.

“The library is the temple of learning, and learning has liberated more people than all the wars in history.”

—Carl T. Rowan.

“Everything you need for better future and success has already been written. And guess what? All you have to do is go to the library.”

—Henri Frederic Amiel.

“A library, to modify the famous metaphor of Socrates, should be the delivery room for the birth of ideas – a place where history comes to life.”

—Norman Cousins.

“London has fine museums, the British Library is one of the greatest library institutions in the world… It’s got everything you want, really.”

—David Attenborough.

“One of the most constant and sustaining truths of my life has been this: I love the library.”

—Deb Caletti.

“I couldn’t go to college, so I went to the library three days a week for 10 years.”

—Ray Bradbury.

“I was born an only child in Vienna, Austria. My father found hours to sit by me by the library fire and tell fairy stories.”

—Hedy Lamarr.

“I’m really a library man, or second-hand book man.”

—John le Carre.

“I spent many hours ensconced in the local library, reading – nay, devouring – book after book after book. Books were my soul’s delight.”

—Nikki Grimes.

“When I read about the way in which library funds are being cut and cut, I can only think that American society has found one more way to destroy itself.”

—Isaac Asimov.

“I’ve got a vendetta to destroy the Net, to make everyone go to the library. I love the organic thing of pen and paper, ink on canvas. I love going down to the library, the feel and smell of books.”

—Joseph Fiennes.

“An original idea. That can’t be too hard. The library must be full of them.”

—Stephen Fry.

“I remember going to a monastery library when I was very young and being surrounded by ancient books. I fell in love.”

—Hans-Ulrich Obrist.

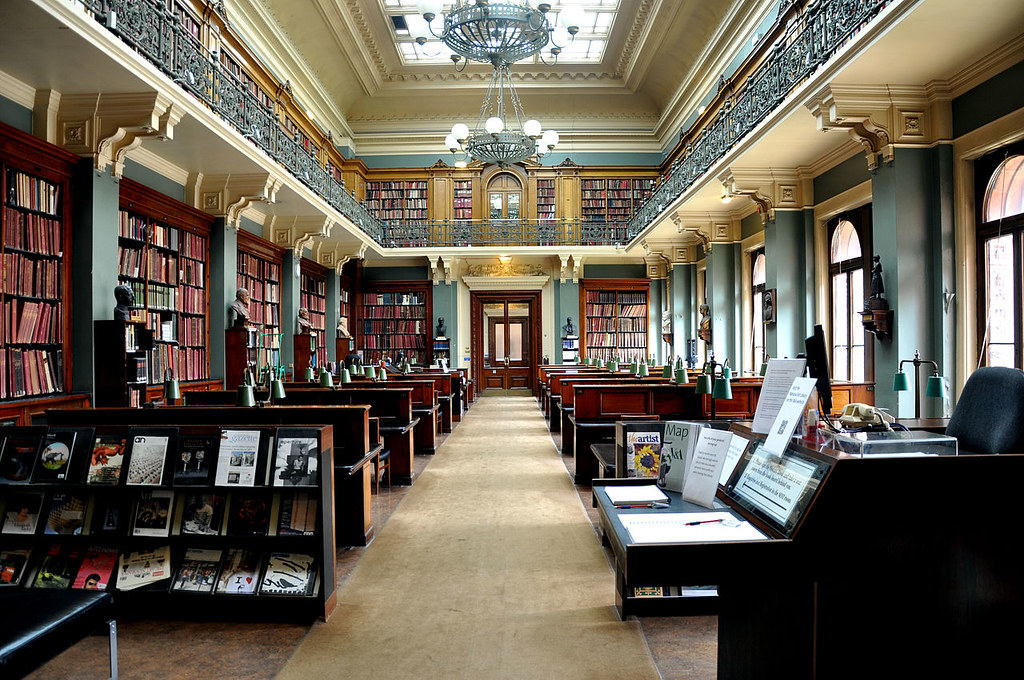

The often palatial libraries of the past are wonderful environments to read, study, or just gaze in awe at such magnificent interiors.

Can modern libraries continue to provide enjoyable spaces for study and pleasure? You decide.

“If we can put a man on the moon and sequence the human genome, we should be able to devise something close to a universal digital public library.”

—Peter Singer.

“There is that romanticized idea of what a bookstore can be, what a library can be, what a shop can be. And to me, they are that. These are places that open doors into other worlds if only you’re open to them.”

—Ruth Reichl.

“The public library system of the United States is worth preserving.”

—Henry Rollins.