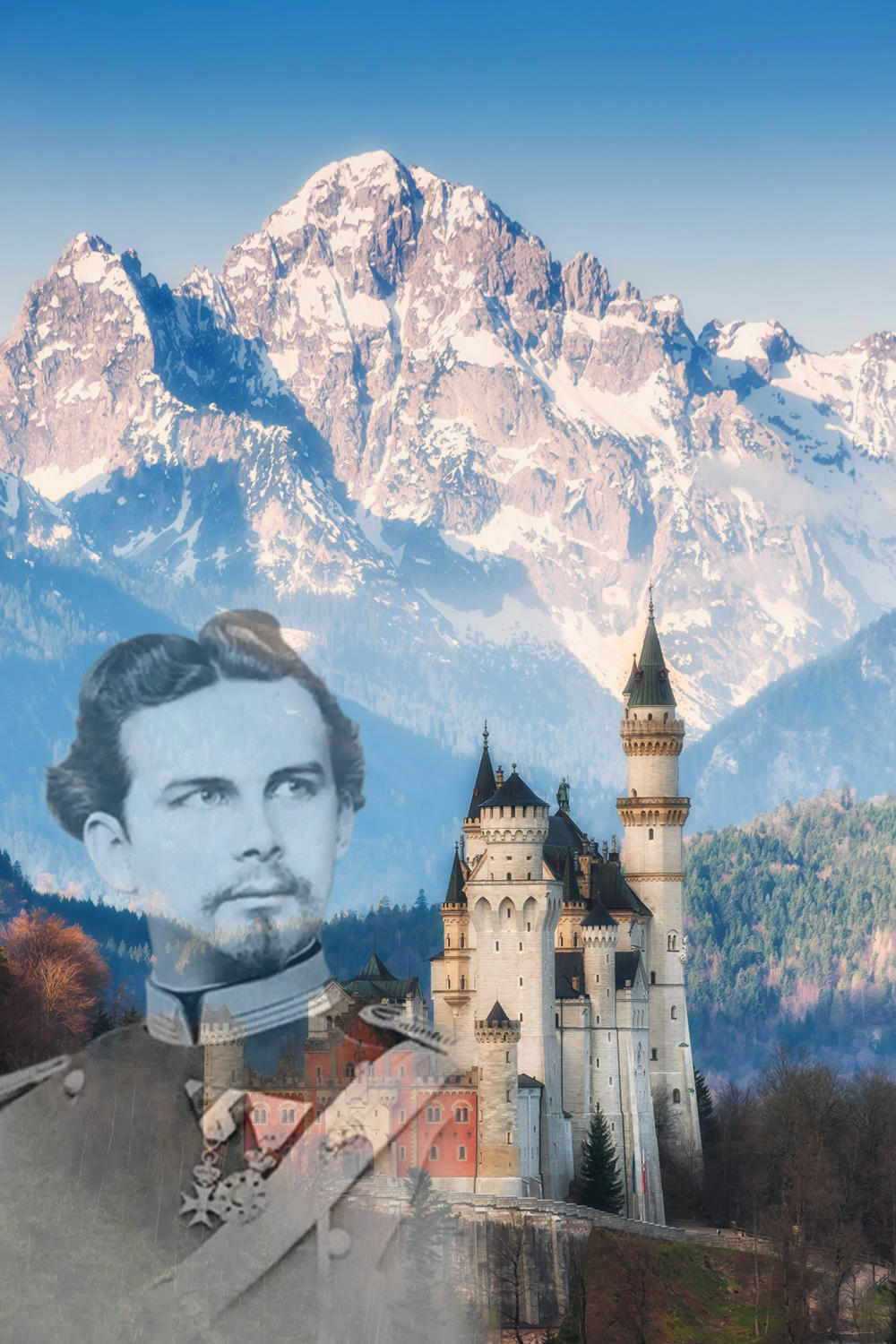

Born in Nymphenburg Palace—the “Castle of the Nymphs”—in Munich, Bavaria, and growing up in the Gothic Revival fantasy castle of Hohenschwangau in the Bavarian Alps, is it any wonder that the creator of Neuschwanstein Castle—King Ludwig II—was prone to day-dreaming?

All around him was picture perfect scenery—glistening lakes, snow-capped mountains, and deep alpine forests.

And he was immersed in a medieval tribute to Bavarian heraldry—particularly the legend of the Knight of the Swan.

The swan looms large in Bavarian folklore. Hohenschwangau means “Upper Swan District”.

Celebrated in the medieval German romance “Parzival” and later in the operas Lohengrin and Parsifal by Richard Wagner, the Knight of the Swan is a medieval tale about a mysterious rescuer who comes in a swan-drawn boat to defend a damsel, his only condition being that he must never be asked his name.

This was the stuff to set a young man’s imagination alight and to dare to dream of building the most beautiful castle in the world—Neuschwanstein.

All it would take was money and time.

Join us as we explore the beauty and history of Neuschwanstein Castle.

Press play button to add musical atmosphere to your journey.

Our story begins in 1864 when the 18-year-old Ludwig II succeeded his father, King Maximilian II, to the throne of Bavaria.

Ludwig did what all kings do and set about planning an ambitious series of palaces and castles.

But Ludwig was different. He was a dreamer with a big imagination.

The inspiration for the construction of Neuschwanstein came from two journeys he took in 1867 — one in May to the reconstructed Wartburg Castle in Germany, another in July to the Château de Pierrefonds in France.

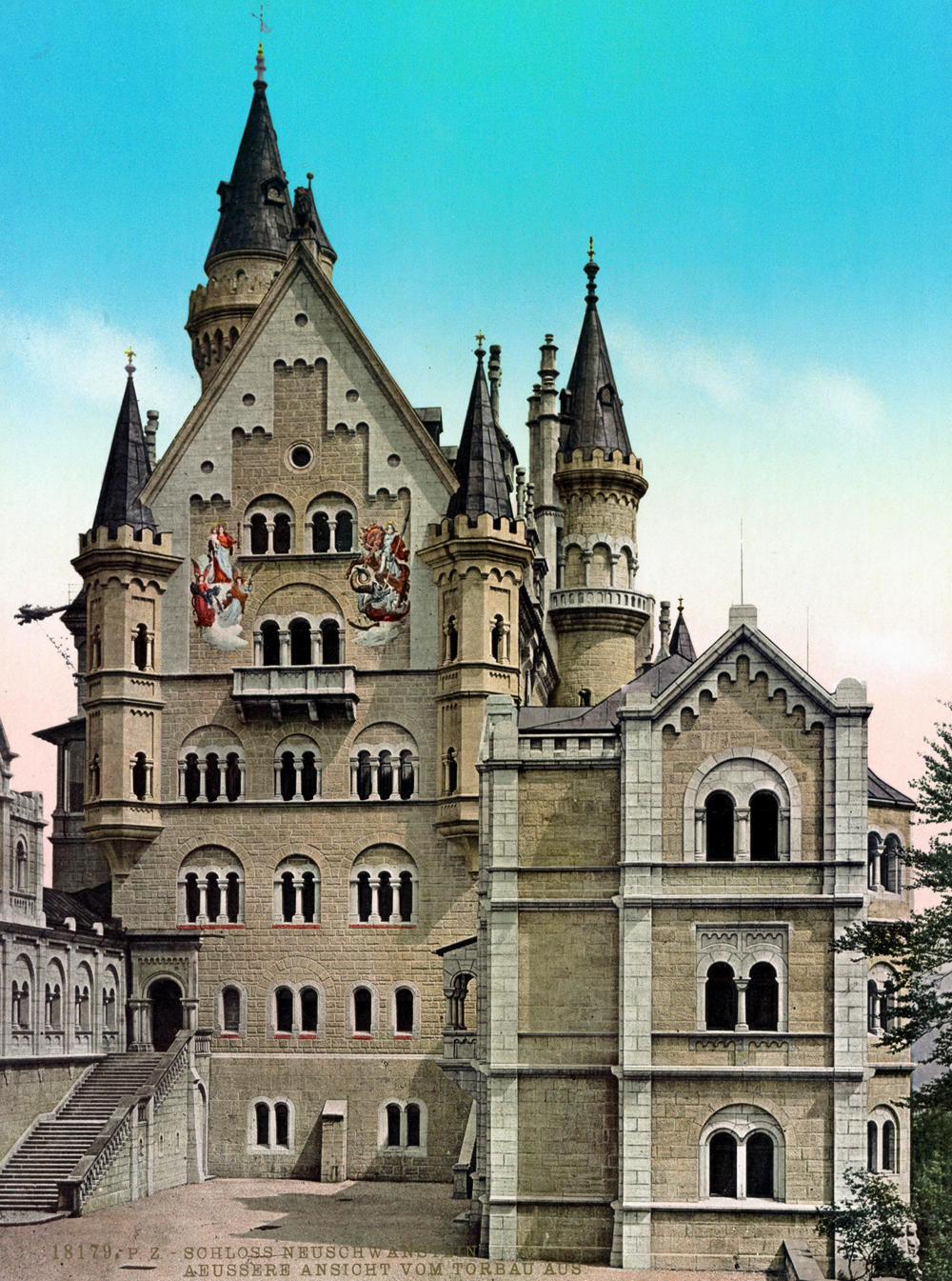

Neuschwanstein can be said to be a combination of these two styles—the Romanesque Palas (the main building housing the great hall) and tower of Wartburg and the numerous ornamental turrets of Pierrefonds.

As an adolescent, Ludwig and his friend read poetry aloud and staged scenes from the Romantic operas of Richard Wagner, which appealed to his fantasy-filled imagination.

He commissioned stage designer Christian Jank to create concepts for Neuschwanstein because Jank had worked on scenery for Richard Wagner’s opera Lohengrin.

Employing about 200 craftsmen, Neuschwanstein’s construction site was the biggest employer in the region for two decades.

Built in the 1860s, Marienbrücke (Mary’s Bridge) is a bridge overlooking Neuschwanstein Castle.

Popular with tourists as a good vantage point for photographs, the bridge spans a large gorge with a waterfall beneath.

The western Palas supports a two-storey balcony with a view on the Alpsee lake.

The entire Palas is spangled with numerous decorative chimneys and ornamental turrets, the court front with colourful frescos.

Fitted with several of the latest 19th-century innovations, the palace had a battery-powered bell system for the servants, telephone lines, hot-air central heating, running warm water, and automatic flush toilets.

The Throne Hall occupies the third and fourth floors and is surrounded by colorful arcades, with paintings of Jesus, the Twelve Apostles, and six canonized kings.

Ludwig’s imagination paid off: Neuschwanstein is magical from any angle and in any season.

His architectural and artistic legacy includes many of Bavaria’s most important tourist attractions.

Even more ambitious than Neuschwanstein was another fairy tale castle planned to replace the ruins of Falkenstein Castle in Pfronten, Bavaria.

But work on Falkenstein never got underway because, by the 1880s, Ludwig’s debt had skyrocketed to 14 million marks.

With no end in sight to his extravagant building projects, the Bavarian government decided to act.

In June of 1886, King Ludwig II was deposed on the grounds of mental illness.

Taken to Berg Castle on the shores of Lake Starnberg, south of Munich, Ludwig took an evening stroll along the lake shore with his personal physician, Bernhard von Gudden.

Allegedly drowned, and possibly murdered, both were found dead that same night.

To this day the details of their deaths remain a mystery.

Only the swans and time know the real story, and they promised to keep it quiet.

Ludwig’s dream lives on, not only in Bavaria but all around the world thanks to Walt Disney’s Sleeping Beauty Castle which took its inspiration from Neuschwanstein.