At the end of World War I, the world desperately needed a scapegoat to help come to terms with four long years of human carnage.

And the widely disliked Kaiser Wilhelm II, Emperor of Germany and King of Prussia, was the man in the firing line.

As the eldest grandchild of Queen Victoria, Wilhelm was a first cousin of the British Empire’s King George V, who called him “the greatest criminal in history”.

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George proposed that the Kaiser be hanged.

After all, he had been responsible for the invasion of neutral Belgium and was instrumental in starting a war that killed tens of millions.

But since 1916—halfway through the war—Germany had become a military dictatorship under the control of Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and his deputy General Erich Ludendorff.

Look at those faces. You didn’t want to mess with these guys.

Wilhelm’s role had been effectively relegated to awards ceremonies and honorific duties for the last two years of the war.

Deserted by his own military High Command, Wilhelm abdicated in 1918 and fled to the Netherlands, ending 400 years of the Hohenzollern dynasty.

Thanking the Dutch government for granting him asylum in the Netherlands, Wilhelm sent this telegram to Queen Wilhemina of the Netherlands on November 11, 1918:

Although article 227 of the Treaty of Versailles called for the prosecution of Wilhelm “for a supreme offense against international morality and the sanctity of treaties”, the Dutch government refused to extradite him, despite appeals from the Allies.

Settling initially in the 17th-century Amerongen Castle in the little village of Amerongen in the central Netherlands, Wilhelm called this home for two years before moving to nearby Doorn village.

And there it was. One day in 1920, while Wilhelm was househunting in Doorn, he spied the place he would call home for the rest of his life.

Owned by Dutch aristocrat Ella van Heemstra—mother of actress Audrey Hepburn—Wilhelm paid 1.35 million guilders for Doorn House.

Originally a moated 14th-century castle, Doorn House had been converted into an elegant country house in the 1790s.

The rear side view shows how deceptively large Doorn House actually is.

Covering 35 hectares with English-style landscaped gardens, the house was filled with antique furniture, paintings, silver, and porcelain from Wilhelm’s palaces in Berlin and Potsdam—30,000 pieces in all, requiring 59 train wagons to transport to Doorn.

Modest by what Wilhelm had become accustomed to, Doorn House was, nevertheless, deceptively large—this imposing building was just the entrance gatehouse that Wilhelm added to the property.

Once through the gatehouse, visitors would pass through more gates to cross a little bridge across a real moat.

The grounds even had an Orangerie used to protect tropical plants during the cold winter months.

The tasteful dining room once hosted an uneasy dinner with the powerful Nazi Party figure, Hermann Göring.

Now a museum, the rooms have been left unchanged since the time the Kaiser lived here.

Doorn House is frozen in time.

Wilhelm even had the saddle that he sat on while working in Berlin shipped to Doorn.

The Doorn House collection includes snuffboxes and watches that belonged to Frederick the Great.

Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands bought this lamp as a gift for the exiled Kaiser and his wife.

A real water closet—a flush toilet inside of an armoire.

Wilhelm liked to surround himself with reminders of Prussia’s military hegemony.

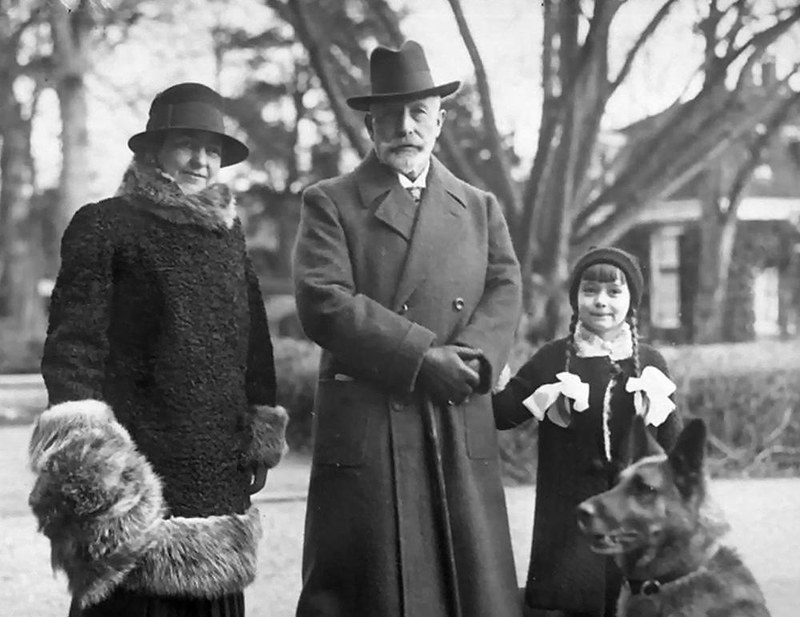

From bombastic Emperor to elderly statesman in exile.

Aging mellows most of us, but was this the case with Wilhelm?

Shortly after moving into Dorn House, Wilhelm learned that his youngest son, Prince Joachim of Prussia, had committed suicide by gunshot.

Believed to be directly related to Wilhelm’s abdication, 29-year-old Joachim could not accept his new status as a commoner and fell into a deep depression.

Affectionately known as “Dona”, Wilhelm’s first wife, who had been his companion for 40 years, died in the spring the following year.

When Wilhelm received a birthday greeting in January of 1922 from the son of a recently widowed German Princess, he invited the boy and his mother to Doorn House.

Finding much in common with Princess Hermine, and both being recently widowed, Wilhelm proposed and the two were married in November, 1922.

Hermine remained a constant companion to the aging emperor until his death in 1941

It would appear that Wilhelm mellowed in later years and settled for a simple life.

He spent much of his time walking the grounds, chopping wood, and feeding the ducks.

There were some great things he had done for Germany.

He promoted art, science, public education, and social welfare.

He sponsored scientific research, helped modernize secondary education, and tried to position Germany at the forefront of modern medical practices.

But historians believe he lacked the personal qualities of a good leader at such a critical juncture in history.

Deeply antisemitic and paranoid about a British-led conspiracy to destroy Germany, he did, however, recognize the evils of Nazism:

Declining an offer of asylum from Winston Churchill when Hitler invaded the Netherlands in May of 1940, Wilhelm must have known the winter of his life was drawing to a close.

He died of pulmonary embolus on 4th June 1941, aged 82, just weeks before the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union.

What a time he had lived through.

A time when Emperors toyed with millions of lives like they were little more than model soldiers in a game of war.

Wilhelm’s dream of returning to Germany as monarch died with him in Doorn, where he is buried in a mausoleum in the gardens.

Not one, but all of mankind’s epitome

Fixed in opinion, ever in the wrong

Was all by fits and starts, and nothing long.

English poet Alexander Pope (1688 - 1744)