Stand on the banks of the River Conwy at night and gaze across at the floodlit Conwy Castle, its eight majestic towers rising to the heavens out of solid rock, and you get the measure of the man that was King Edward I (1239–1307).

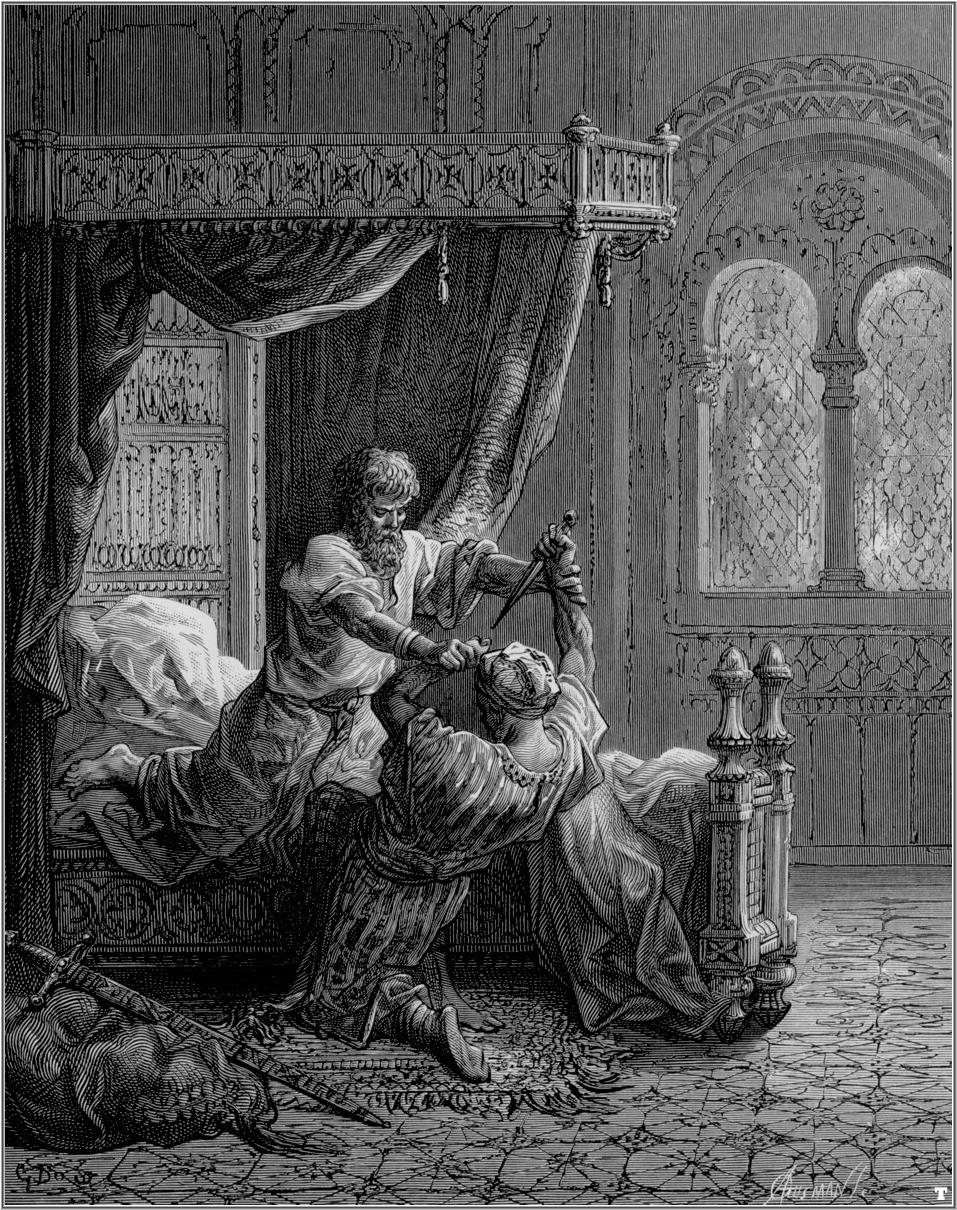

At 6ft 2in tall, Edward towered above his contemporaries. A man to be feared, who could intimidate, but a man who earned respect as a warrior, an administrator, and a man of faith.

Nicknamed “longshanks”, meaning “long legs” or “long shins”, some historians believe his height and long limbs gave him an advantage in battle—all the better for wielding the sword.

The Iron Ring

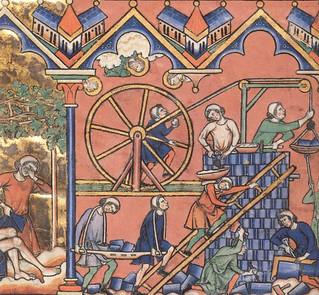

To prevent further Welsh uprisings, Edward started building massive stone fortifications known as the Iron Ring—the most ambitious project of its kind in Europe. Some castles had been built by his father, which he strengthened, but his focus was building huge new fortifications in Gwynedd.

The Castles and Town Walls of King Edward in Gwynedd, North Wales is a UNESCO-designated World Heritage Site, which includes the castles and town walls of Caernarfon and Conwy, and the castles of Harlech and Beaumaris.

UNESCO considers the sites to be the “finest examples of late 13th-century and early 14th-century military architecture in Europe.

Contains affiliate links

Press play to add atmosphere as we journey back in time to Wales circa 1283.

Caernarfon Castle

“the fairest castle that man ever saw”

Built to showcase Edward’s power, Caernarfon was more palace than castle—an administrative center fit for a king.

The polygonal towers and banded colored stone give it a unique appearance compared with Edward’s other castles.

Legend holds that when Roman Emperor Magnus Maximus was out hunting one day, he rested under a tree and fell asleep. He had a dream of a fort, “the fairest that man ever saw”, at the mouth of a river in a mountainous country.

Nearby Caernarfon, a Roman fort called Segontium once stood. Edward believed it was the castle in Maximus’s dream and decided to build the fairest castle that man ever saw at the mouth of the River Seiont in the mountainous country of Wales. Caernarfon Castle is born of a dream.

Conwy Castle

Defended by eight towers and two barbicans, Conwy Castle sits on a coastal ridge overlooking the estuary of the River Conwy.

The castle would originally have been white-washed using a lime render. What a sight that must have been on a sunny day—a white castle shimmering in the sunlight.

Visitors entered through a barbican, complete with drawbridge and portcullis. Conwy has the oldest stone machicolations in Britain—openings through which stones, or other objects, could be dropped on attackers.

Both Caernarfon and Conwy have walled towns adjacent to the castle. This meant that the town and castle were mutually dependent on each other—the castle giving protection and the town providing trade.

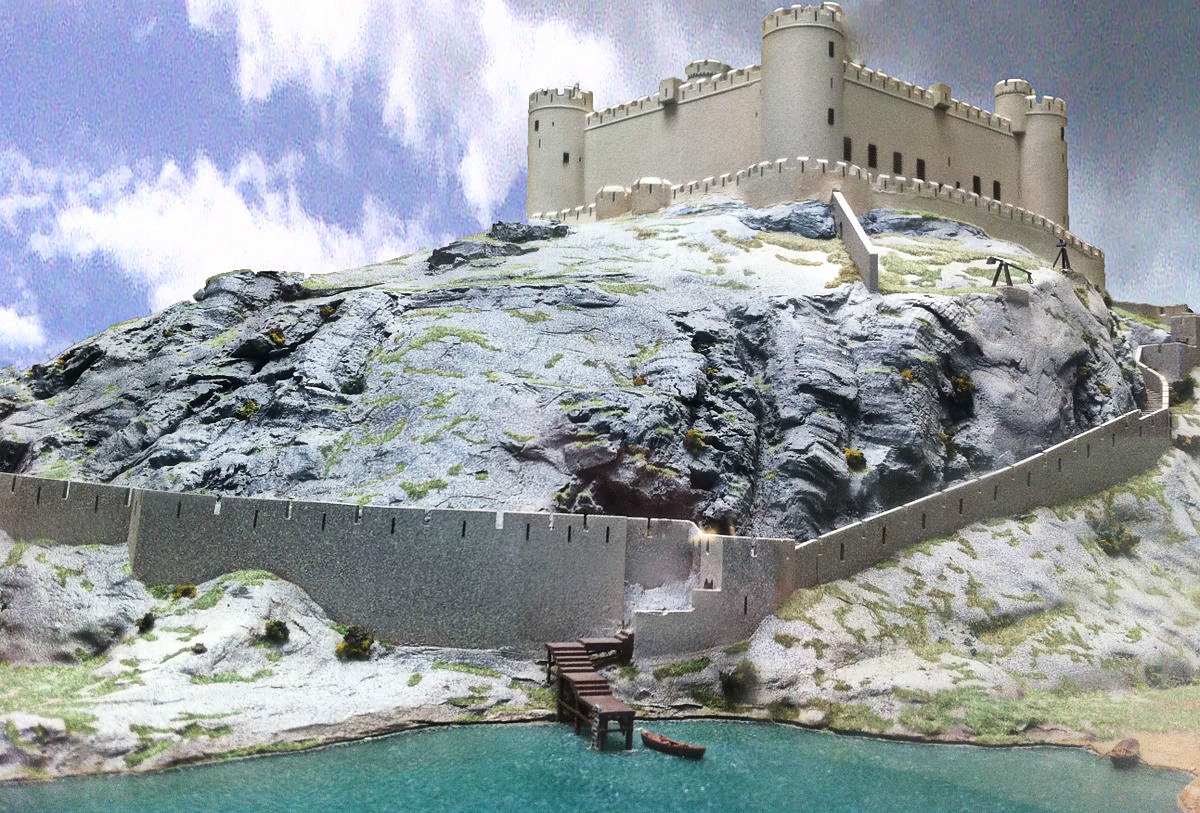

Harlech Castle

Harlech Castle is built high on a rocky outcrop with a commanding view of the Irish Sea and surrounding countryside.

Its concentric design features a massive gatehouse that is thought to have provided accommodations for high-ranking visitors.

Housed within an inner wall were a great hall, chapel, granary, bakehouse and small hall.

In the 13th century, the sea came much further inland to the outer wall, which ran around the base of the outcrop, allowing the castle to be resupplied by boat during a siege.

Beaumaris Castle

Setting Beaumaris apart from the other castles in the UNESCO-designated Iron Ring is its location on the Isle of Anglesey as opposed to mainland Wales.

Distinguished medieval historian Dr Arnold Joseph Taylor CBE, called Beaumaris the “most perfect example of symmetrical concentric planning” in Britain.

The massive fortifications include an outer ward (a courtyard encircled by a wall) with twelve towers and two gatehouses, protecting an inner ward with six massive towers and two enormous gatehouses.

Like Harlech, Beaumaris could also be supplied by sea in the event of a siege.

The Prince of Wales

In 1284, a baby boy was born in Caernarfon Castle—the future King Edward II.

In hopes that it would help pacify Wales, Edward I bestowed on his son the title “Prince of Wales”. As a 16th-century clergyman put it,

To this day, the heir to the throne is titled “Prince of Wales”.

Sources

Wikipedia

Prestwich, Michael (2010), Edward I and Wales.

Maddicott, John (1994), Simon de Montfort.

Wheatley, Abigail (2010), Caernarfon Castle and its Mythology.

Powicke, F. M. (1962), The Thirteenth Century, 1216–1307.

Ashbee, Jeremy (2007), Conwy Castle.

Brooks, Richard (2015), Lewes and Evesham 1264-65; Simon de Montford and the Barons’ War.

Taylor, Arnold (2004) [1980], Beaumaris Castle (5th ed.)

cadw.gov.wales