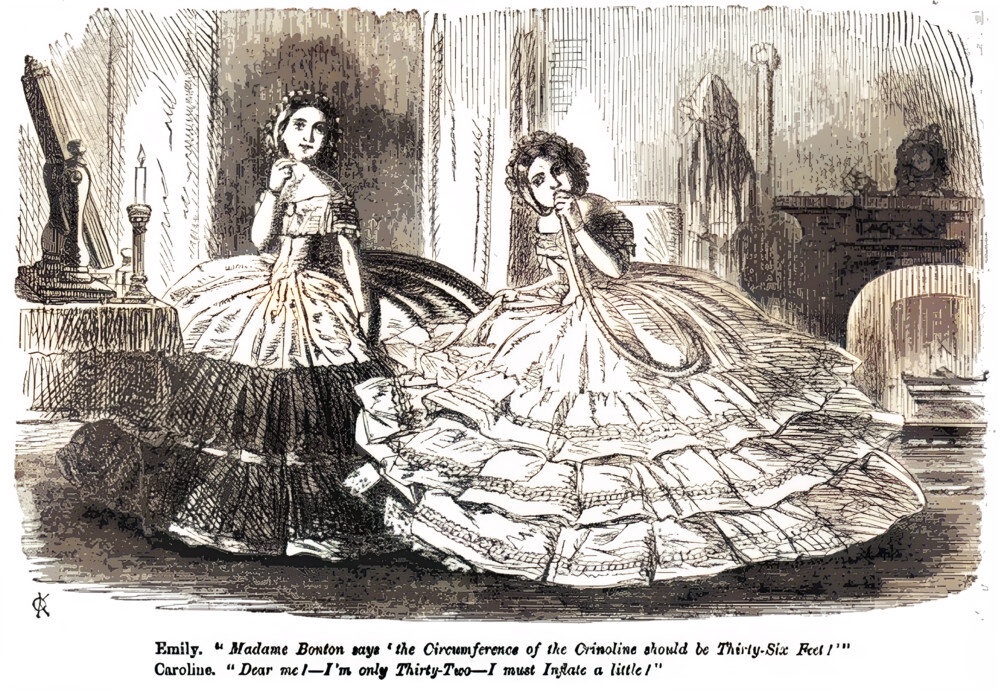

Just as we chuckle today at the absurd dimensions reached by Victorian crinolines, so too did Victorians themselves.

Shown here is an early inflatable (air tube) version of the crinoline by George Cruikshank, from The Comic Almanack, 1850. Crinolines wouldn’t actually come into wide use until a few years later.

In this humorous example, the exaggerated size of the crinoline meant that the gentlemen had to use long-handled trays (“baker’s peels”) to offer food and drink to their ladies.

If there was one thing such broad crinoline skirts guaranteed the wearer, it was plenty of personal space.

The fashion became so popular that Punch nicknamed the crinoline craze “Crinolinemania”.

And it’s not difficult to see why—even today, the bell-shaped profile of a crinoline-supported dress lends a fairytale quality to a wedding.

No doubt the impression left by a beautiful Princess and Empress had a bearing on the success of the crinoline.

Here are 10 facts about the crinoline—some of which you may find surprising.

1. The 16th-century Spanish farthingale was the grandmother of the crinoline

Wide and full skirts were popular as far back as the 15th century.

Queen Consort Joan of Portugal made the hoop skirt popular when she wore one to court.

Originally called the Spanish verdugado and later corrupted to “farthingale” in English, it was alleged that Joan wore it to help hide an illegitimate pregnancy.

There’s nothing like a bit of court gossip to help a fashion’s popularity.

Introduced to England by Catherine of Aragon when she married the ill-fated 15-year-old Arthur, Prince of Wales, the Spanish farthingale was a petticoat of linen with bands of cane, or whalebone inserted horizontally at intervals.

Gradually widening from the waist to the hem, the cone-shape of the Spanish farthingale became popular with European sovereigns for the remainder of the 16th century.

2. The crinoline gets its name from horsehair

Described as a combination of the French words crin, meaning horsehair, and lin meaning linen, the name essentially describes the materials used to make the original crinoline, i.e. horsehair and linen.

Used from the early 1840s, the horsehair crinoline supported the weight of other petticoats under the increasingly full, bell-shaped skirts that had become popular.

Horsehair crinolines reduced the number of required petticoats to achieve the desired profile and offered more freedom of movement for the wearer’s legs.

But they were heavy, uncomfortable, hot and unhygienic—especially during the summer.

What was needed was something lighter, but with more structure. Enter the cage crinoline.

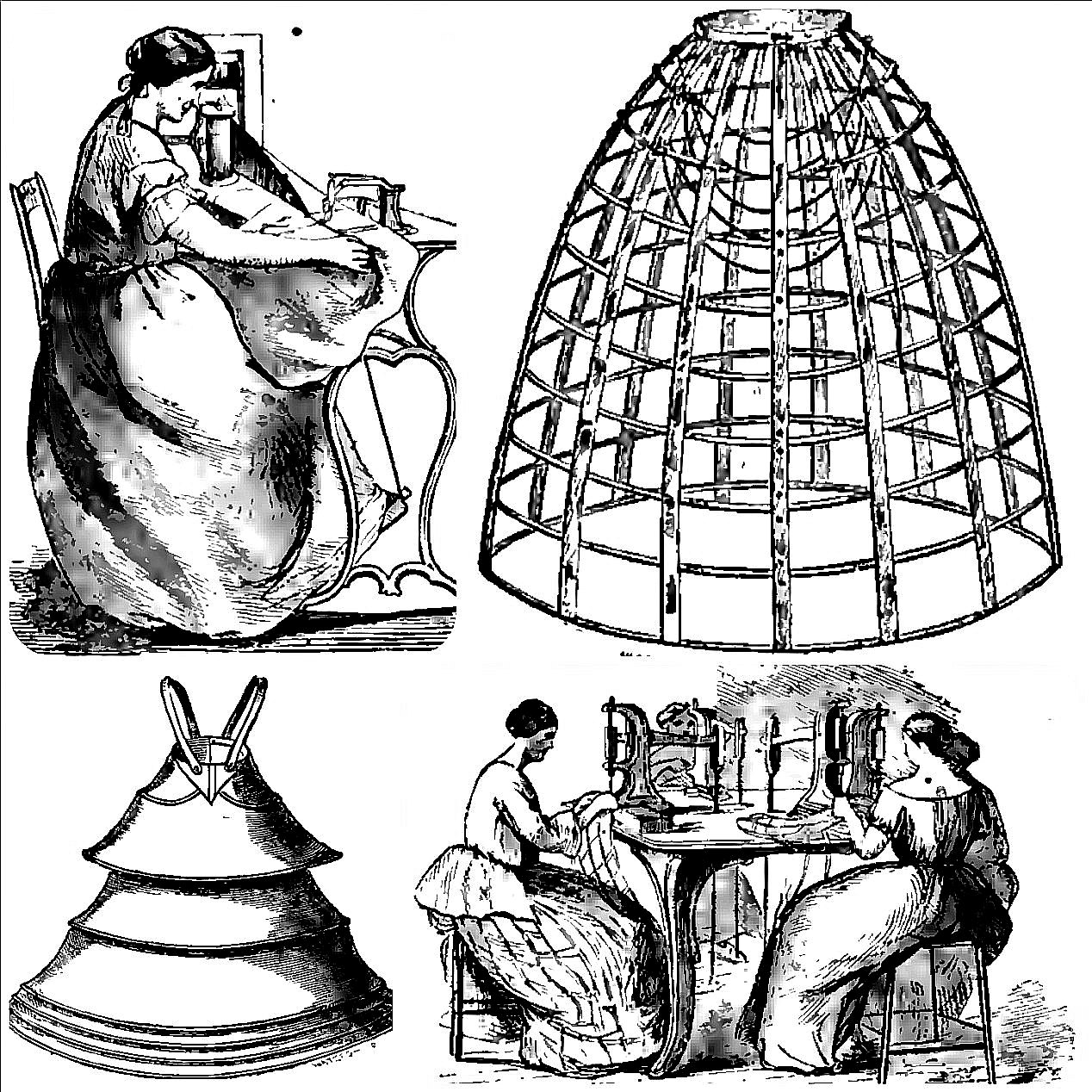

3. Cage crinolines were lightweight and highly flexible

The steel-hooped cage crinoline, first patented in April 1856 by R.C. Milliet in Paris, and by their agent in Britain a few months later, became extremely popular.

Although cage crinolines looked very rigid, the spring steel they were made from was very flexible and could be compressed. Aside from the inevitable accidents, women learned how to walk in crinolines and how to sit down in them without revealing underclothes.

Because the spring steel was very lightweight, far from restricting women, they were liberating, freeing women from multiple layers of petticoats worn in prior decades.

The Lady’s Newspaper of 1863 enthusiastically praised the cage crinoline:

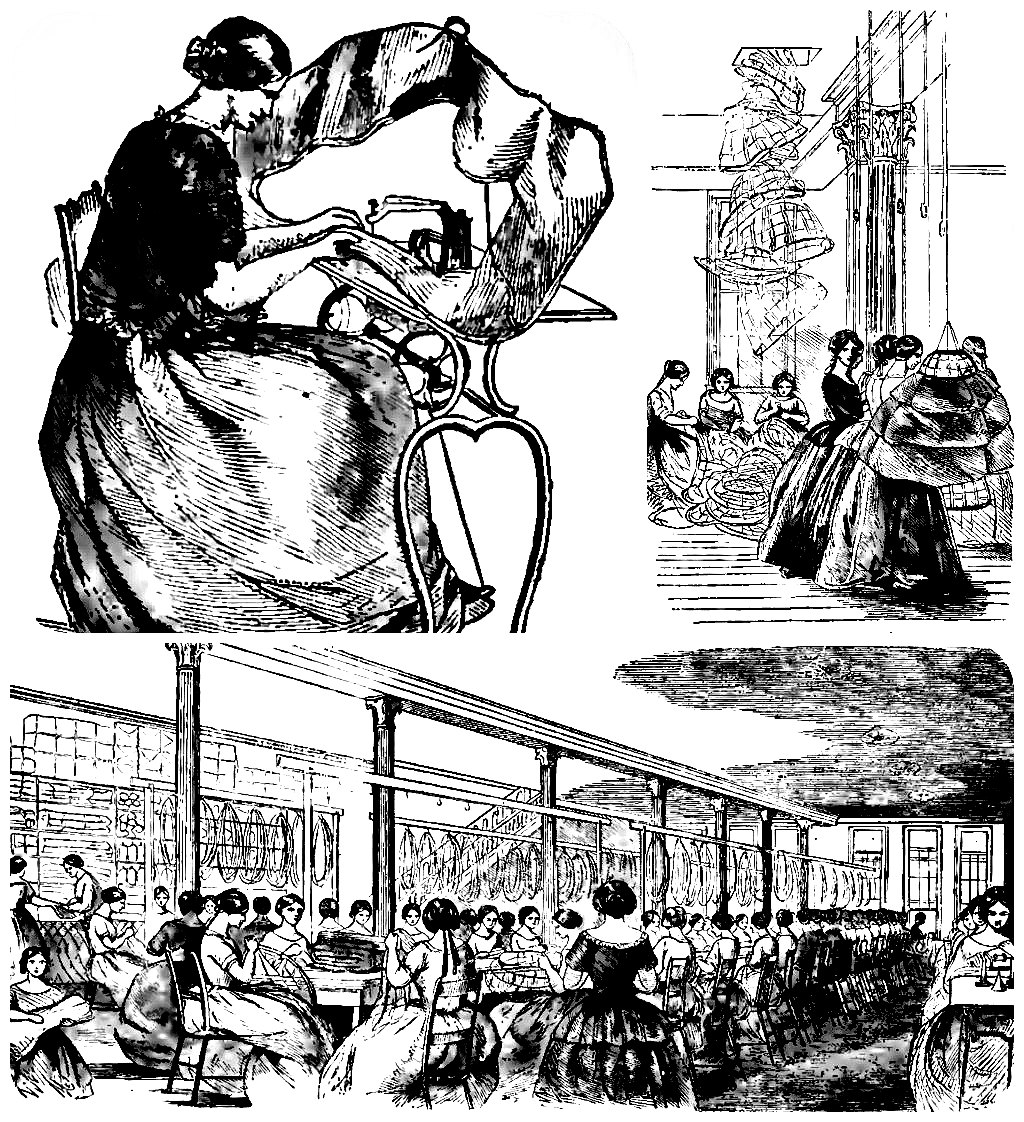

4. Cage crinolines were mass-produced in huge quantity

One of the biggest producers was Douglas & Sherwood’s Hoop Skirt Factory in New York. It employed 800 women and produced in excess of 8,000 hoop skirts each day.

To make the hoops required a ton of steel per day, and each month the factory would get through 150,000 yards of muslin, 100,000 feet of whalebone, 24,000 spools of cotton, 2,800,000 eyelets, 500,000 yards of tape, 225,000 yards of cord, and 10,000 yards of haircloth.

5. There were accidents with crinolines, some tragic and fatal

Overzealous advertising tried to reassure potential customers that their freedom of movement would be unhindered by wearing a cage crinoline.

This gave a false sense of security about the level of care and attention that was needed to avoid accidents while wearing them.

Not being constantly aware of exactly where the extremities of the dress were could lead to tragedy.

Thousands of women died in the mid-19th century as a result of their hooped skirts catching fire.

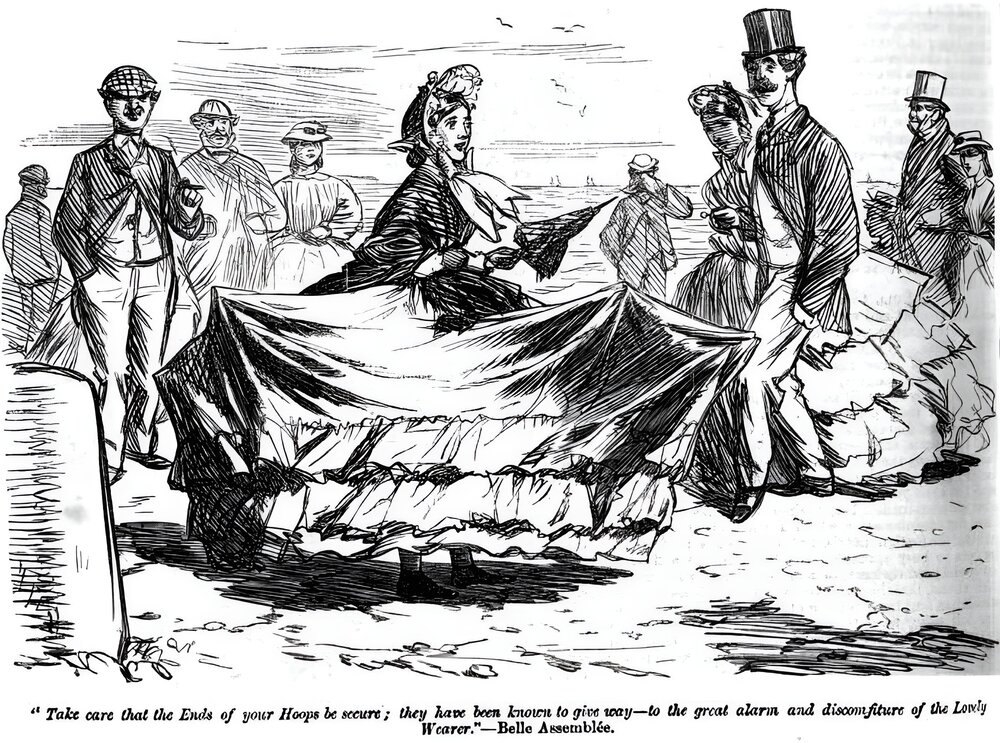

Other hazards included the hoops being caught in machinery, carriage wheels, gusts of wind, or other obstacles.

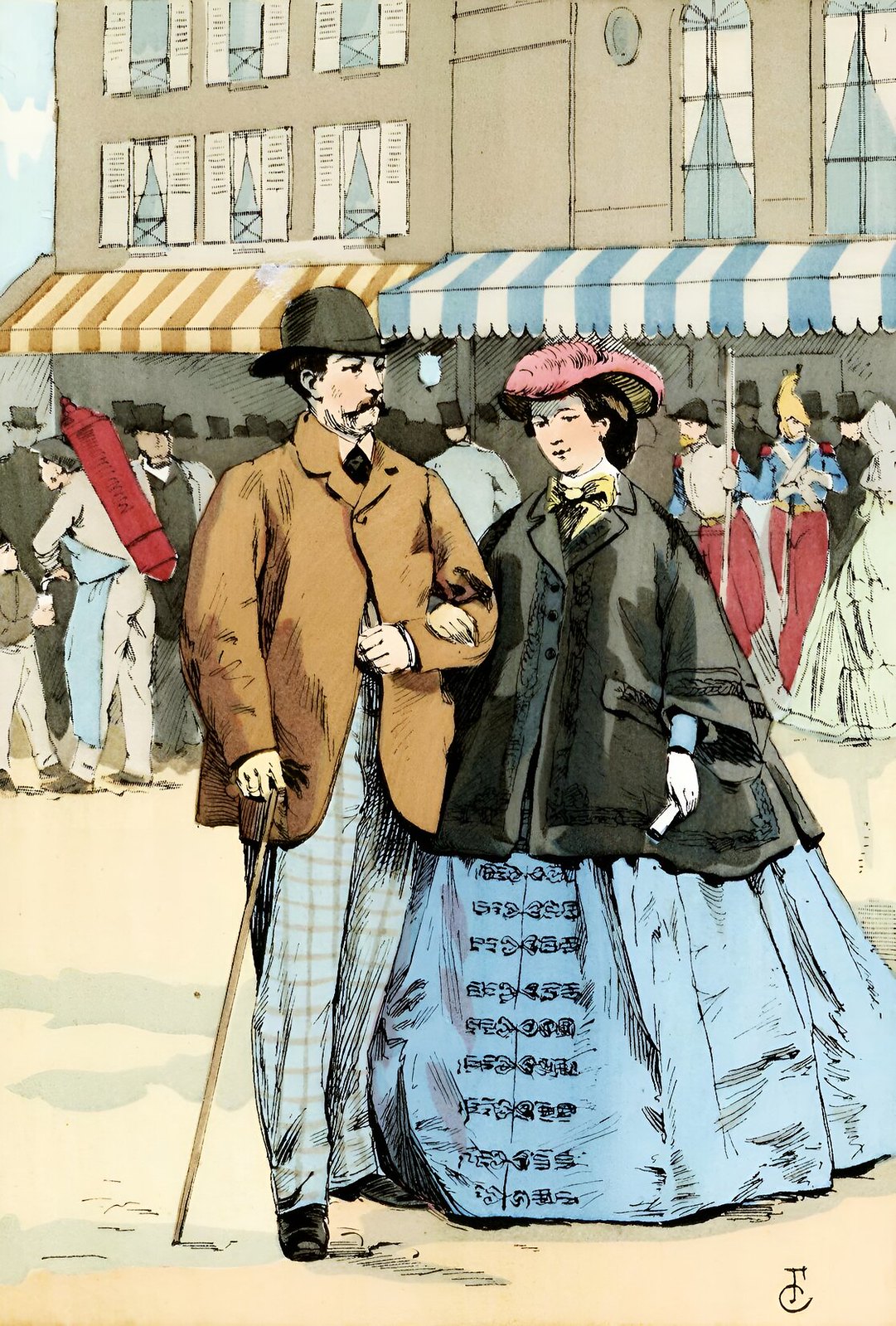

6. Crinolines crossed class barriers

Crinolines were worn by women of every social standing and class across the Western world, from royalty to factory workers.

7. Crinolines reached 18 feet in circumference

At its widest point, the crinoline could reach a circumference of up to six yards—providing the perfect opportunity for satirical cartoons to exaggerate dimensions even further.

Contemporary photographs show that many women wore smaller versions of the crinoline, as opposed to the huge bell-shaped creations so often seen in fashion plates. Large crinolines were probably reserved for balls, weddings and other special occasions.

8. Media scrutiny

Widespread media scrutiny and criticism followed the crinoline, from journal articles to poems decrying the fashion, to songs complaining about them.

The crinoline also came under heavy fire from moralists, publicists, and satirists who often condemned the fineries of fashion and sensationalized the most extreme situations—none more so than London’s satirical magazine Punch and New York’s Harper’s Weekly.

9. Queen Victoria is said to have detested crinolines

Queen Victoria is said to have inspired a song in Punch:

“But it’s all the rage, my dear.”

“I’ll be the one in a rage if I have to go in this.”

When Queen Victoria’s daughter was married to the Prussian Prince Frederick in 1858, the queen requested the Prussian ladies not to wear crinolines because there was not enough room in the Chapel Royal at St. James’s Palace.

This incident probably led many to believe she disliked crinolines, but numerous photographs show her wearing one.

10. The crinoline craze reached its peak during the early 1860s

Falling out of favor by about 1862, the silhouette of the crinoline changed from bell-shaped to flatter at the front with the fullness projected out more behind.

Called the “crinolette”, it was typically composed of “half hoops” made of the same spring steel

Crinolettes would bridge the gap until the next big fashion craze to sweep the world appeared—the Bustle.

References:

Illustrated Encyclopedia of World Costume by Doreen Yarwood

Tudor Costume and Fashion by Herbert Norris

Corsets & Crinolines in Victorian Fashion by Lucy Johnstone, V&A Museum

Victorian and Edwardian Fashion: A Photographic Survey by Alison Gernsheim