French artist Auguste Toulmouche (1829 – 1890) loved to tell stories. But instead of putting quill to paper, he put brush to canvas.

His paintings share the academic style of the Académie des Beaux-Arts that dominated French art in the mid 19th century.

Playing in Toulmouche’s favor was a trend that lent itself to storytelling—a move towards greater idealism. Although painted in the mid-Victorian era, his themes were often set in the Regency revival and late Georgian periods.

Let us examine 12 paintings from Albert Toulmouche … and the stories they tell.

With the prevalence of mobile technology today, it is very hard for us to imagine a time when people relied on letters as their primary means of communication across distance.

Dropping the envelope at her feet, this beautiful lady was obviously keen to open the letter from her lover in a hurry.

Moving near the light of the window, she remains standing. If it were bad news, would she be so hasty?

The letter probably has sweet words for her eyes only—and her corner position in the room gives her the privacy she needs.

Not all news is good news, as the young lady above might be finding out. She’s left the letter on the table and turned away from it, as if rejecting its message.

Is her fiancé away at war? Has something happened to him? She looks concerned, but not devastated. Perhaps she was expecting his return sooner …

Yet again, it could be bad news from her sister. What story do you think the painting tells?

Not a happy bunny …

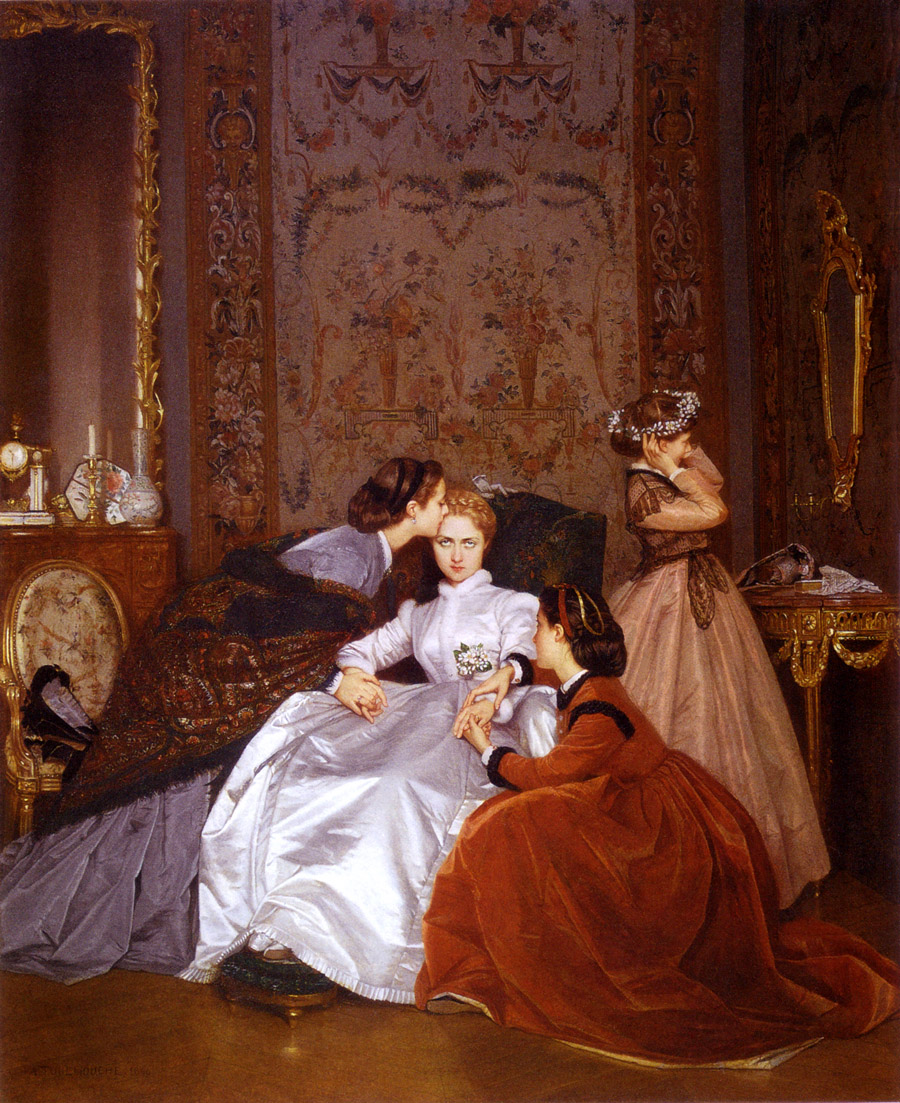

This young lady is not at all sure she’s doing the right thing. In an age when many marriages were for social standing or financial security, marriage for love was something more akin to dreams than reality.

In a letter to her niece Fanny Catherine Knight, Jane Austen reminded her of how elusive perfection can be:

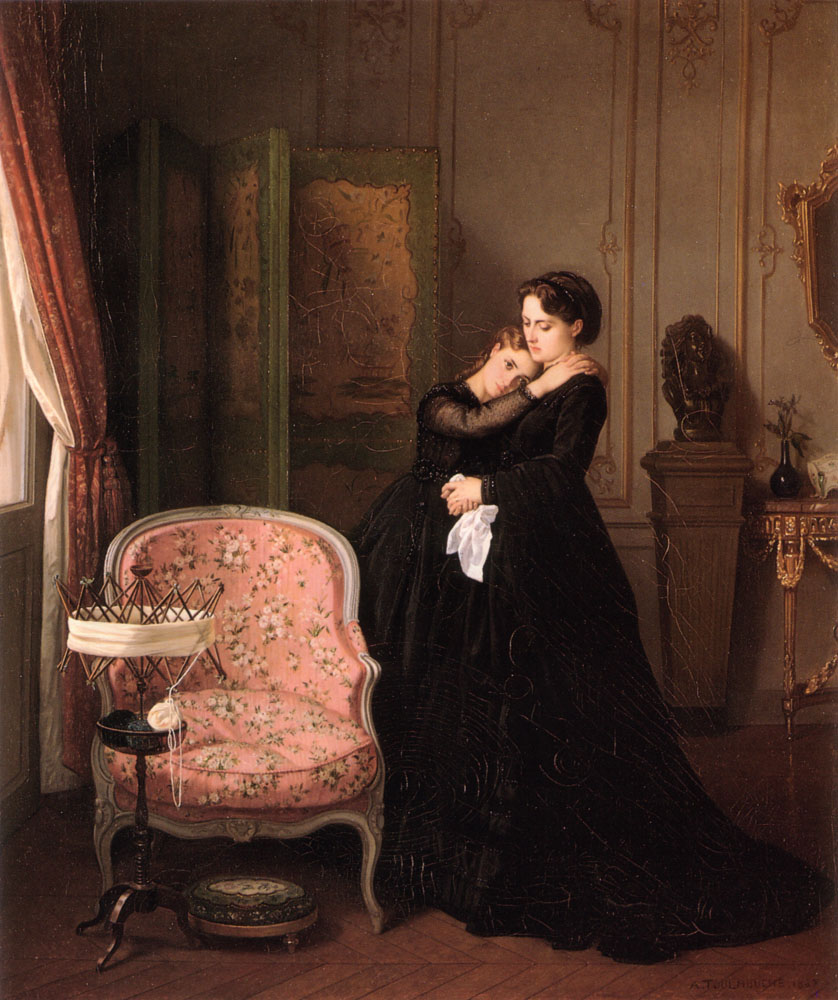

Families were large, but life was precious. Children died young and mothers were lost during childbirth. Cholera, consumption, and smallpox didn’t care how much money people had—they took the lives of rich and poor alike.

The period theme of Toulmouche’s paintings was a time of war. Many a young handsome officer would have fallen in battle.

Grieving and consolation touched everyone at unexpected times.

Novels helped fuel the hopes and dreams of readers. Have you felt this way when reading—so moved that you had to pause and contemplate the moment?

The 18th-century view that reading contemporary novels was a time-wasting leisure activity gave way to 19th-century ideals on their ability to educate.

While Jane Austen’s novels critiqued the life of the British landed gentry, by the mid-1800’s, the most widely read novel in England was the anti-slavery Uncle Toms Cabin of 1852 by American Harriet Beecher Stowe.

A good book and an afternoon nap. Doesn’t get much better than that, does it?

It was an age when meal times were strictly adhered to. Breakfast would have been eaten early, leaving a long wait until evening for the main meal of the day.

The Duchess of Devonshire reported having a “sinking feeling” mid-afternoon. We’ve all felt that way, haven’t we? Now we can top-up with countless energy snacks and drinks, but the Duchess had another idea—afternoon tea.

Notice also the chinoiserie screen behind the ladies, reflecting the importance of Chinese motifs in Western culture.

Mirror, mirror on the wall …

It was a time when keeping up appearances was critical to maintaining social standing.

But perhaps Auguste Toulmouche was using parody to message a decadent Victorian audience.

Romanticism—an artistic, literary, and intellectual movement of the first third of the 19th century—initiated a surge of enthusiasm for all things Greek, including Greek mythology.

In Greek mythology, Narcissus was fixated with his own physical appearance and disdained others around him. Nemesis, the spirit of divine retribution against those who succumb to hubris, attracted him to a pool where he fell in love with his own reflection. Unable to take his eyes of his own image, he lost the reason for living and died, staring at his reflection.

Here’s an interesting painting. The lady is warming her hands and feet at the burning fire, but taking care not to let the heat tinge her complexion with redness. Another reason that made the fan such an indispensable accessory for the 19th-century lady.

Is there more to this story? Is she burning a love letter … ?

What are friends for but to listen to our stories and grievances? The lady on the right seems genuinely concerned for her friend, or perhaps they are sisters.

The painting reminds us that simple pleasures like a stroll in a park or garden, and sharing polite conversation in good company, are some of the best things in life.

It’s five minutes past three by the trusty wall clock. Why hasn’t he called? Oh yes, phones haven’t been invented yet …

But back to that clock. During the 19th century, pendulum clocks were some of the most accurate timepieces in existence. Any household that could afford one depended on it.

Conceived by Galileo Galilei in around 1637, the daily life of the 19th century revolved around the pendulum clock.

Hope you enjoyed our time together, strolling through Auguste Toulmouche’s little storybook of history.