For Victorians, flowers were the language of love.

Proclaiming feelings in public was considered socially taboo, so the Victorians expressed intimacy through flowers.

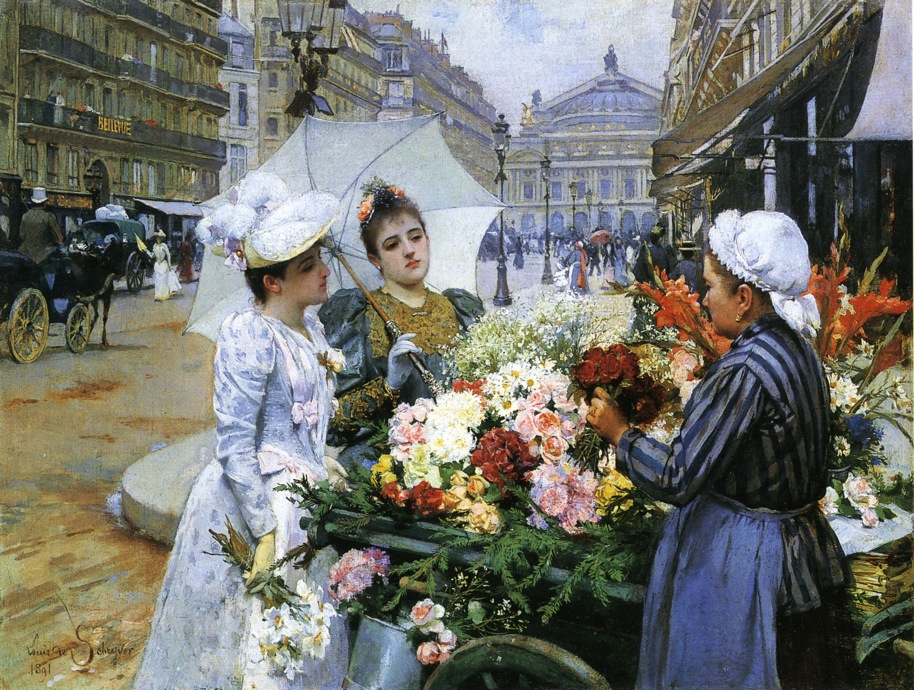

Myriad market stalls and street sellers sprang up to cater to the Victorians’ need to communicate covertly.

Learning the particular meanings and symbolism assigned to each flower gave Victorians a way to play the subtle game of courtship in secret.

Coded into gifts of blooms, plants, and floral arrangements were specific messages for the recipient, expressing feelings that were improper to say in Victorian society.

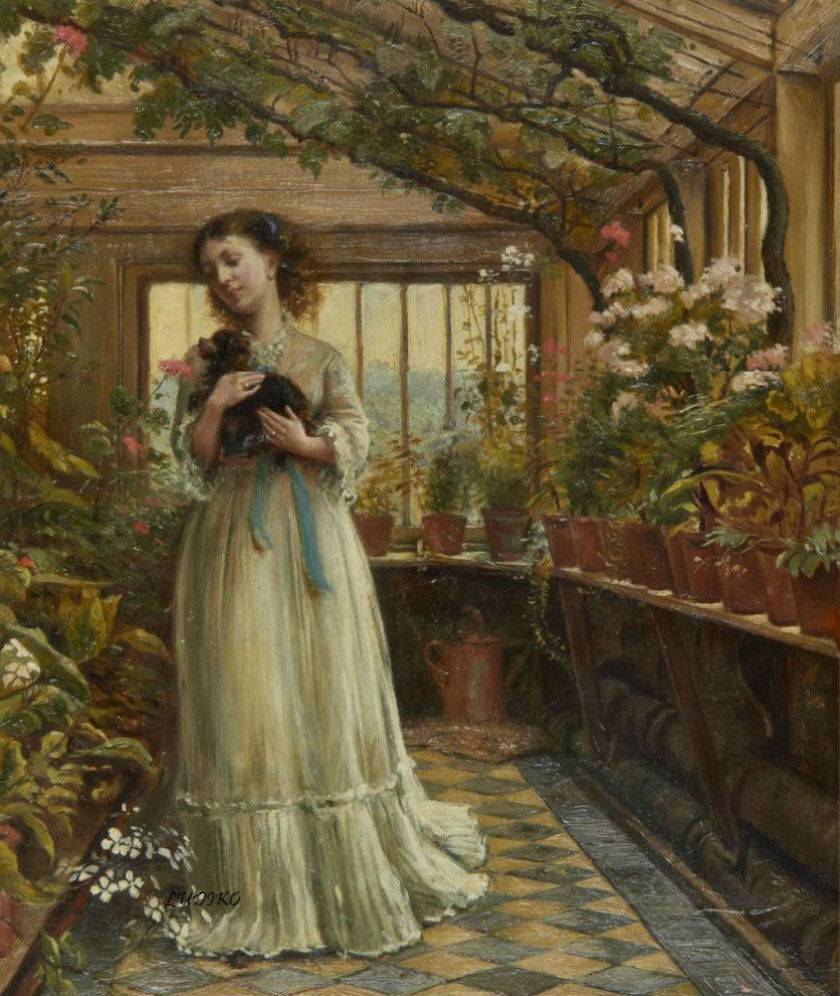

Alongside the language of flowers was a growing interest in botany.

Housing exotic and rare plants, conservatories enjoyed a golden age during the Victorian era, while floral designs dominated interior decoration.

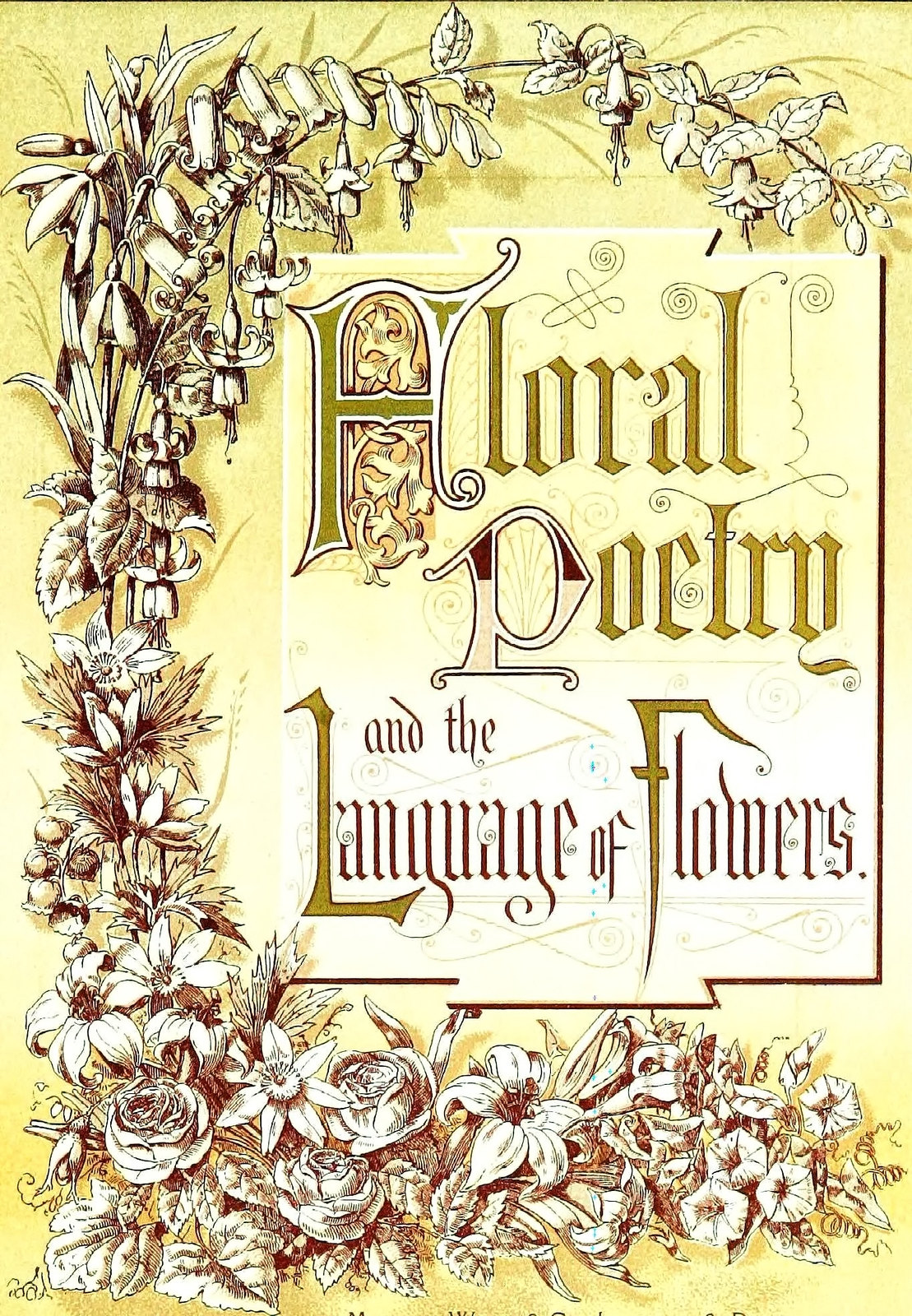

Dedicated to the “language of flowers” were hundreds of guide books, with most Victorian homes owning at least one.

Often lavishly illustrated, the books used verbal analogies, religious and literary sources, folkloric connections, and botanical attributes to derive the meanings associated with flowers.

The appearance or behavior of plants and flowers often influenced their coded meanings.

Plants sensitive to touch represented chastity, whereas the deep red rose symbolized the potency of romantic love.

Pink roses were less intense than red, white suggested virtue, and yellow meant friendship.

To express adoration, a suitor would send dwarf sunflowers.

Myrtle symbolized good luck and love in a marriage.

At her wedding in 1858, Princess Victoria, the eldest child of Queen Victoria, carried a sprig of myrtle taken from a bush planted from a cutting given to the Queen by her mother-in-law.

Thus began a tradition for royal brides to include myrtle in their bouquets.

In the royal wedding of 2011, Catherine Middleton included sprigs of myrtle from Victoria’s original plant in her own wedding bouquet.

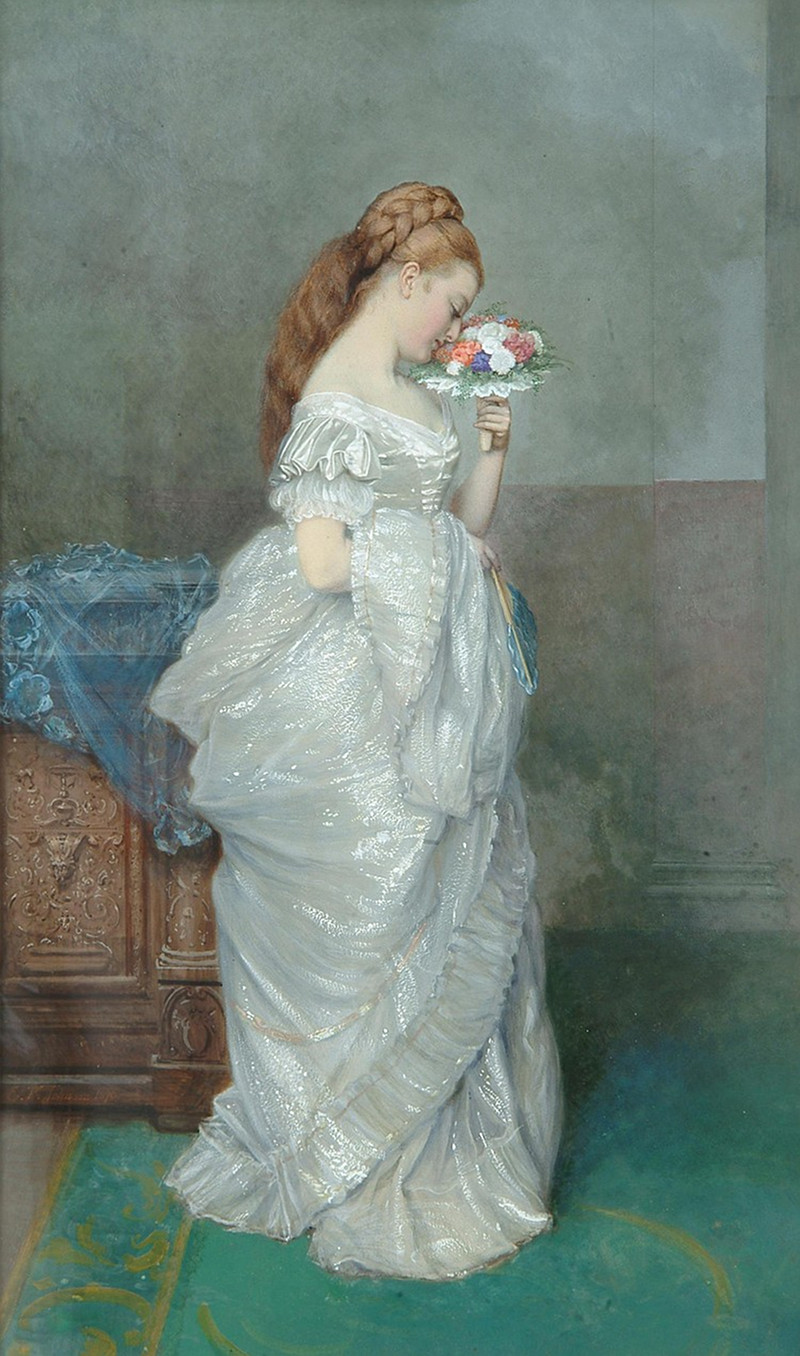

Displaying small “talking bouquets” or “posies” of meaningful flowers called nosegays or tussie-mussies became popular.

Decorative “posy holders” with rings or pins allowed them to be worn and displayed by their owners.

Made from brass, copper, gold-gilt metal, silver, porcelain, glass, enamel, pearl, ivory, bone and straw, the holders often had intricate engravings and patterning.

Other Flower Meanings

| Burdock | Importunity. Touch me not. |

|---|---|

| Buttercup (Kingcup) | Ingratitude. Childishness. |

| Camomile | Energy in adversity. |

| Carnation, Striped | Refusal. |

| Chrysanthemum, White | Truth. |

| Coltsfoot | Justice. |

| Crocus | Abuse not. |

|---|---|

| Daffodil | Regard. |

| Daisy | Innocence. |

| Jasmine | Amiability. |

| Dandelion | Rustic oracle. |

|---|---|

| Dogwood | Durability. |

| Dragonwort | Horror. |

| Ivy | Fidelity. Marriage. |

| Everlasting Pea | Lasting pleasure. |

|---|---|

| Elderflower | Zealousness. |

| Fennel | Worthy all praise. Strength. |

| Lemon Blossoms | Fidelity in love. |

| Flytrap | Deceit. |

|---|---|

| Foxglove | Insincerity. |

| Anemone | Forsaken. |

| Lavender | Distrust. |

| Marigold | Uneasiness. |

|---|---|

| Hemlock | You will be my death. |

| Hibiscus | Delicate beauty. |

| Honeysuckle | Generous & devoted affection. |

Who will buy?

The film versions of Oliver! and My Fair Lady made the London flower sellers famous, but their life was far harsher than their Hollywood depictions.

So high was the demand for flowers that it created many opportunities for street traders and the exploitation of child labour.

Victorian social researcher Henry Mayhew wrote about flower sellers in his book London Labour and the London Poor, 1851—a groundbreaking and influential survey of the city’s poor: