On May 28, 1588, the Spanish Armada set sail from Lisbon, Portugal, headed for England with 130 ships and 30,000 men.

Meaning literally “Great and Most Fortunate Navy”, the Spanish Armada’s strategic goal was to overthrow Queen Elizabeth I and put an end to Protestantism in England.

In so doing, Spain also hoped to stop English and Dutch privateering in the Spanish Netherlands.

Here’s our list of 10 surprising facts about the Spanish Armada.

1. The English fleet significantly outnumbered the Spanish Armada

It might be surprising to discover that the English had a lot more ships—200 ships to the 130 of the Spanish. But the Spanish threat lay in their firepower, which was 50% greater than the English.

2. No Spanish ships were lost to the English fire ships

Waiting for additional troops from the Duke of Parma’s army to join the invasion, the Spanish fleet lay at anchor off the Coast of Calais in northern France.

In a surprise attack, the English sent eight fire ships downwind into the closely anchored Spanish vessels.

Although no Spanish ships were actually lost to fire, it caused them to scatter and break their defensive “crescent formation”, allowing the English to attack.

3. The Spanish had to “cut and run” to save their fleet

Many of the Spanish ships had to “cut and run” to escape the English fire ships at Calais. Meaning to make a cowardly retreat, the phrase “cut and run” that we use today originates from the navy and in literal terms means to cut the anchor line and sail downwind, leaving the anchor behind.

4. The Battle of Gravelines changed the future of naval warfare

After the Spanish ships had scattered, the Duke of Medina Sidonia, commanding the Armada tried to regroup at a small port between Calais and Dunkirk called Gravelines in what is now Northern France.

The English had observed the Spanish tactics of firing guns once and then for the marines onboard to jump to the rigging to prepare for boarding the enemy ships. Knowing this, the English ships provoked Spanish fire while staying out of range, then moved in for the kill with repeated broadsides at close range.

In this scenario, many experienced Spanish gunners were killed, but the regular marines did not know how to operate the big guns effectively.

Up until this time, gunnery had played a supporting role to ramming and boarding in naval battles. The English tactic of standing off and firing decisive broadsides proved the more effective and would see England’s Royal Navy become the dominant military force for the next 300 years.

5. The Gulf Stream played a big part in the fate of the Armada

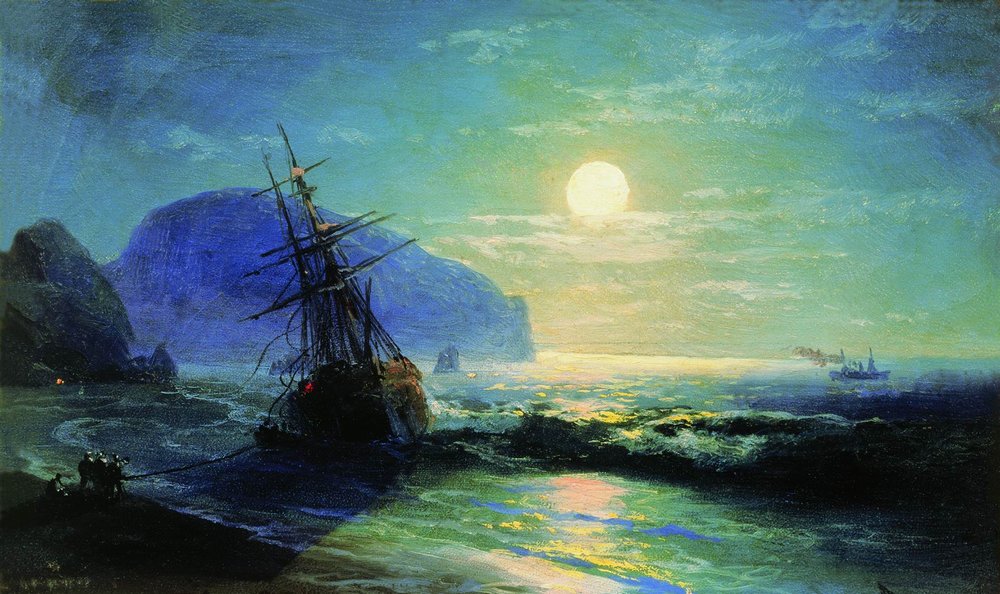

When the Armada had sailed around Scotland in 1588 and entered the North Atlantic, they thought they were sailing west into the safety of the open seas. But the strong Gulf Stream ocean current pushed the ships northeast.

This meant that when they turned to sail south, they were too close to the shore and were driven onto the rocks off the coast of Ireland in strong westerly winds, becoming shipwrecked. Without their anchors, they were unable to secure a position and wait out the stormy weather.

6. The “Little Ice Age” may have helped doom the Spanish fleet

The year of the Spanish Armada in 1588 was marked by unusually strong North Atlantic storms, a characteristic of the “Little Ice Age” which was a period of cooling in the northern hemisphere causing unusually bad weather. As a result, the cold and stormy weather caused significantly more loss of life than did direct combat.

7. Of the 130 Spanish ships sent against England, only 67 survived the attack

The literal meaning of Spanish Armada is “great and most fortunate navy”. But of the 130 ships and some 30,000 men setting sail from Spain, only 67 ships and 10,000 men survived to tell the tale. An enraged Philip II of Spain declared,

“I sent the Armada against men, not God’s winds and waves.”

8. The English launched a counter Armada which also failed

A fleet of warships was sent to Spain by Queen Elizabeth I in 1589 to try to capitalize on the advantage England had after the loss of the Spanish Armada. The campaign resulted in the defeat of the English fleet with heavy loss of lives and ships. The Spanish victory once again gave Philip II’s navy the upper hand against England, with Spain ruling the waves for another decade.

When English forces attacked the city of Corunna as part of the English counter Armada in May 1589, Maria Pita was helping her husband defend the city walls. A crossbow bolt hit her husband in the head, killing him. Maria grabbed a spear and killed an English soldier scaling the wall. She appeared on the heights of the wall shouting: Quen teña honra, que me siga (“Whoever has honor, follow me!”), rallying the Spanish troops and driving back the English.

9. A 12th-century Abbey’s barn held 397 Spanish sailors prisoner

Torre Abbey’s barn was originally built to store grain, hay and other farm produce as payment of taxes to the Abbey. But in 1588, the barn in Torquay, Devon, served another purpose. It held 397 Spanish prisoners captured by Sir Francis Drake, for fourteen days and became known as the “Spanish barn”.

Having been dissolved by Henry VIII some 50 years earlier, the Abbey church was ruined but several major outbuildings were left intact.

Today, it is the best preserved medieval monastery in Devon and Cornwall.

Resulting from an extensive remodeling in the 18th century, a Georgian manor house occupies part of the site and houses a permanent art exhibition.

10. The English Victory was acclaimed as the greatest since Agincourt

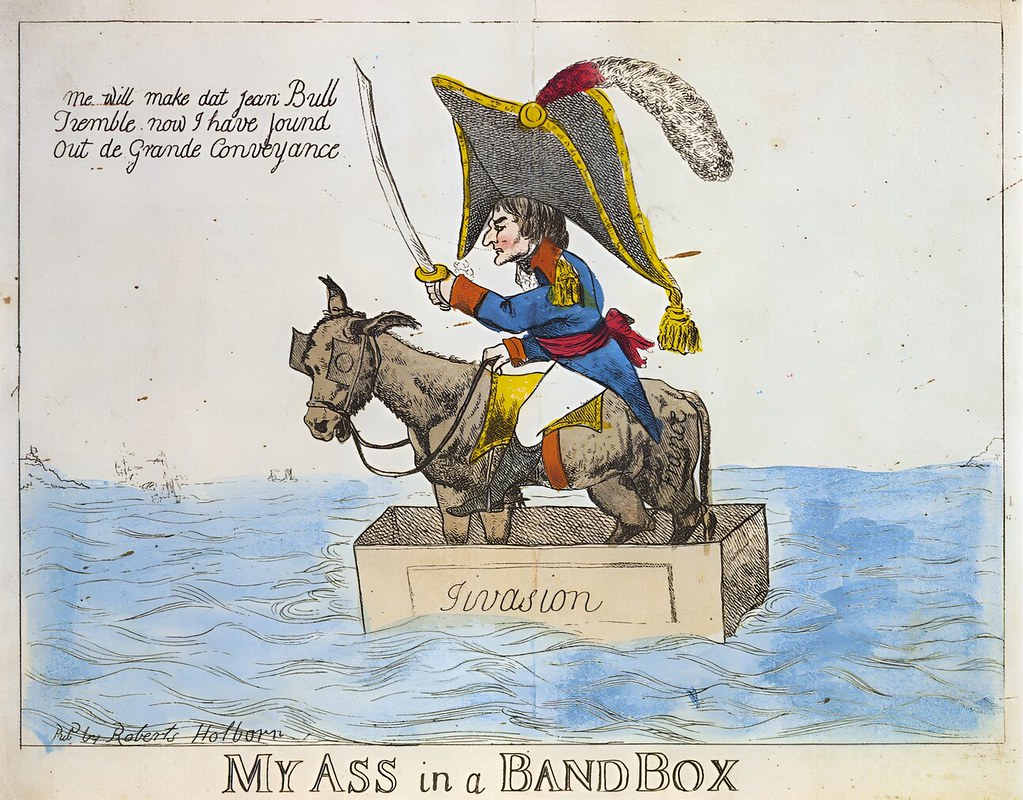

“He came, he saw, he fled.”

Used by the English as a play on the words of Julius Caesar to refer to a swift, conclusive victory, the Armada had been anything but conclusive for Spain.

But this was one of England’s greatest moments.

Spain would send two further armadas against England in 1596 and 1597, and both would be scattered by storms and fail.

Britain would face the real danger from invasion again during both the Napoleonic Wars and the Second World War.

During the Spanish Armada, Britain proved that superior naval tactics, coupled with the British weather are an invincible combination!