The rags to riches story of Czech Art Nouveau artist Alphonse Mucha.

Living alone in Paris in 1894, Alphonse Mucha barely made enough money to feed himself.

There had been better times. Back home in Moravia, he had worked in a castle restoring portraits and decorating rooms with murals. Those were the days. His employer, the Count, had encouraged Mucha to take formal studies and had provided financial support.

Now, at 34, with his savings gone, Mucha was scraping a living from his artwork, taking small commissions from magazine pictures, designs for costumes in operas and ballets, and book illustrations.

But his fortunes were about to change.

Just before Christmas 1894, he happened to drop into a print shop and heard that Sarah Bernhardt—the most famous actress in Paris—was starring in a new play, Gismonda.

The promoters needed a poster to advertise the production, and so Alphonse Mucha offered to deliver a lithograph in two weeks.

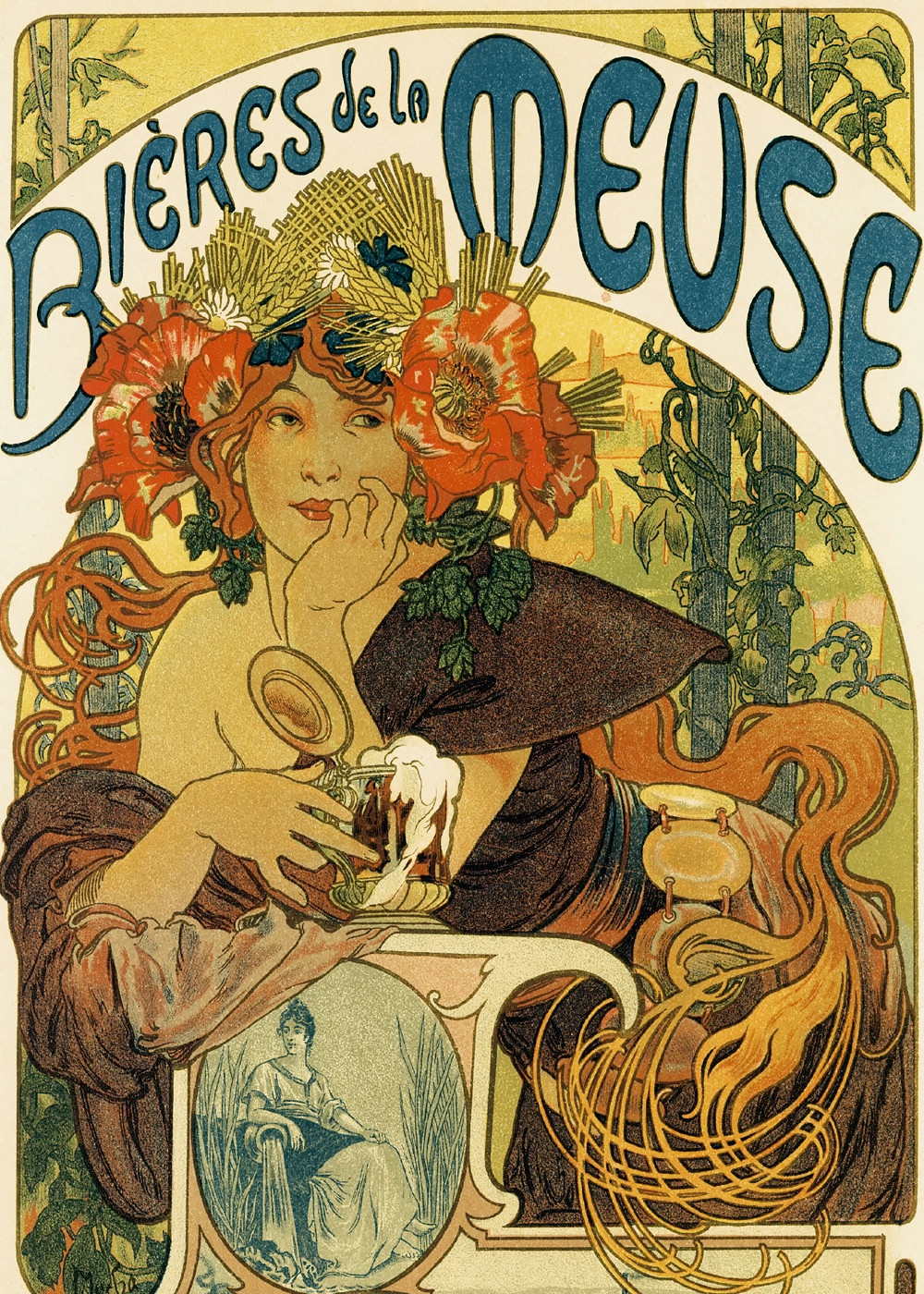

It was an overnight sensation. Bernhardt was so pleased with the success of this first poster that she offered him a six-year contract.

Alphonse Mucha had brought Art Nouveau to the people of Paris.

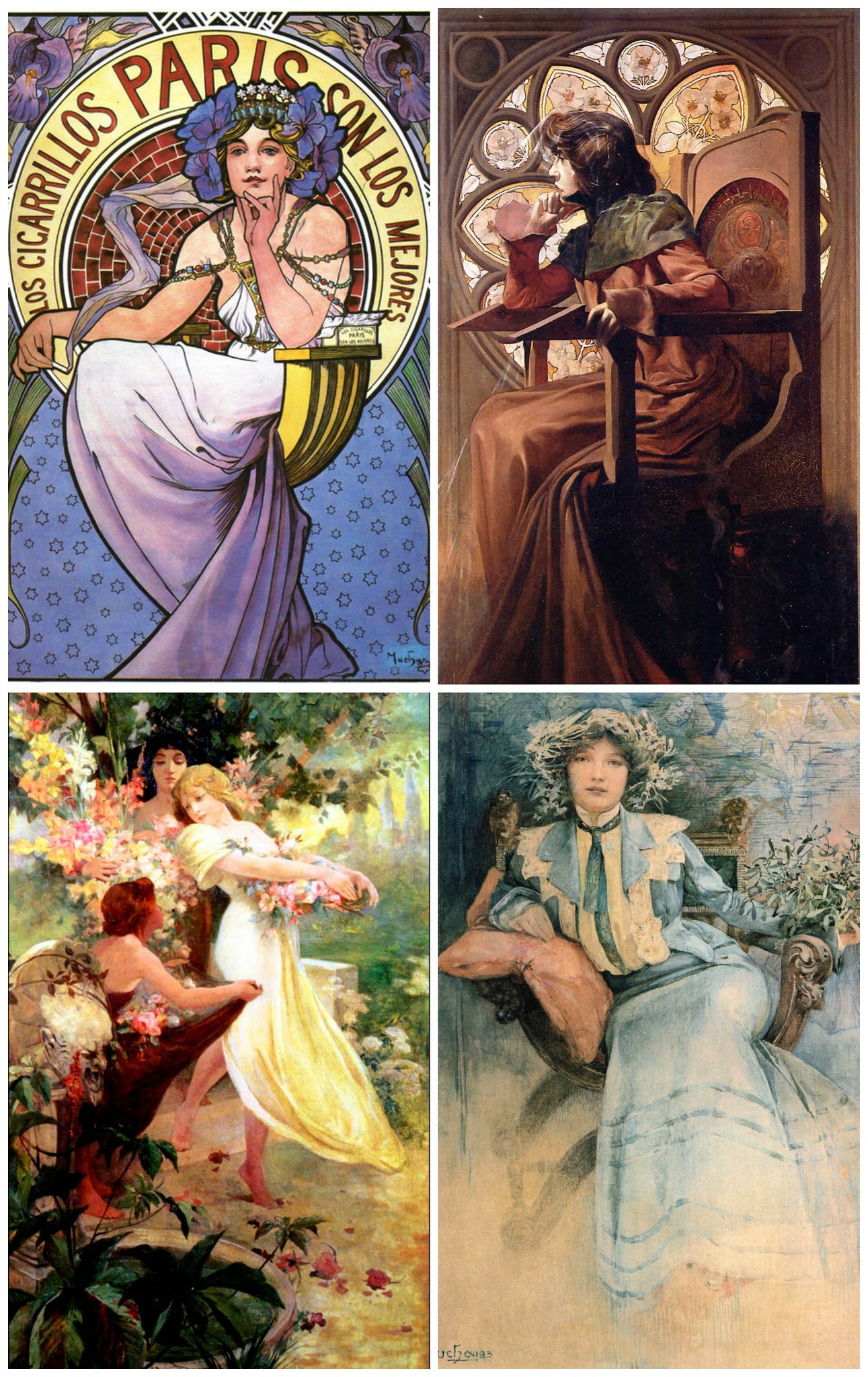

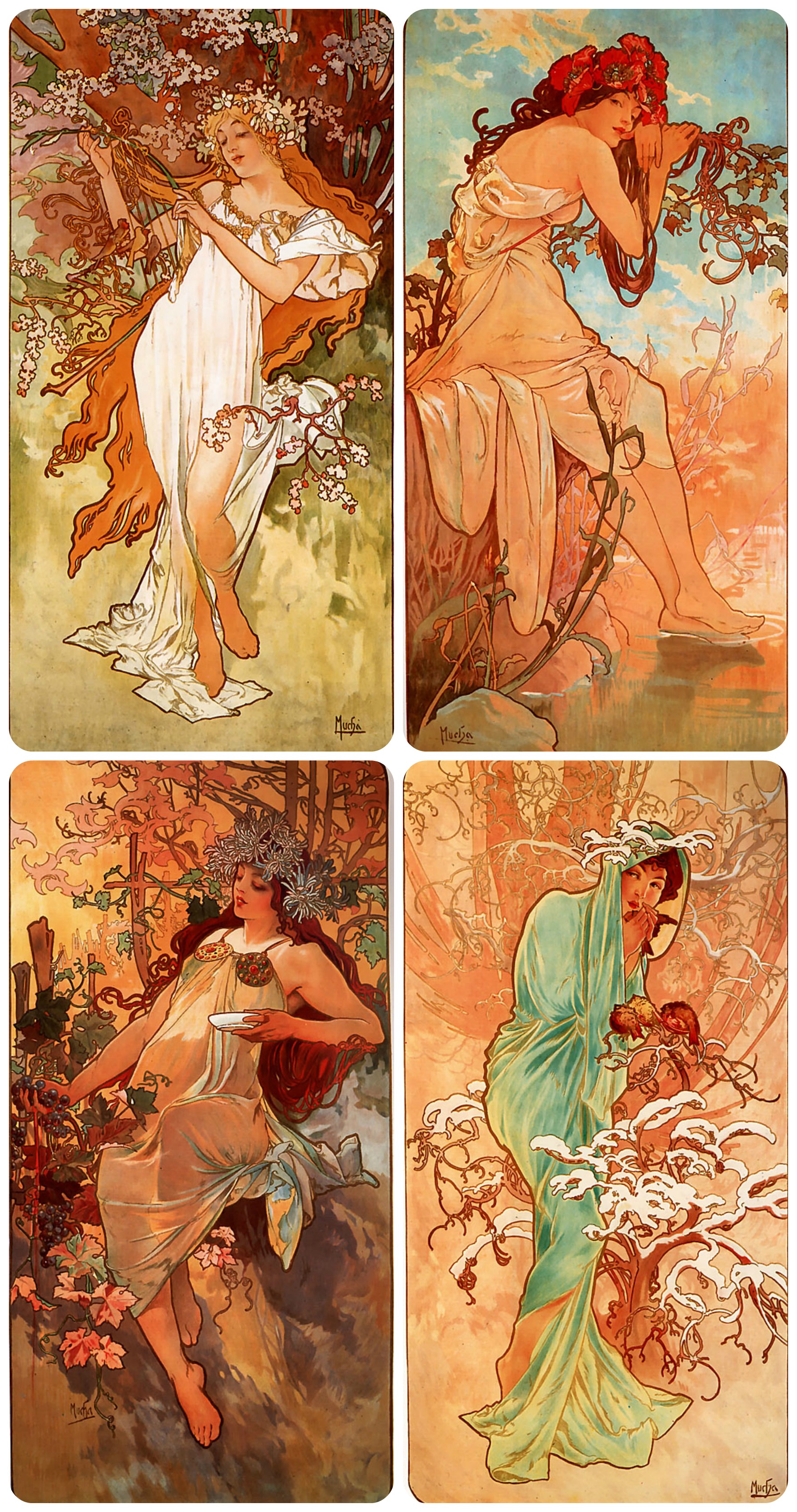

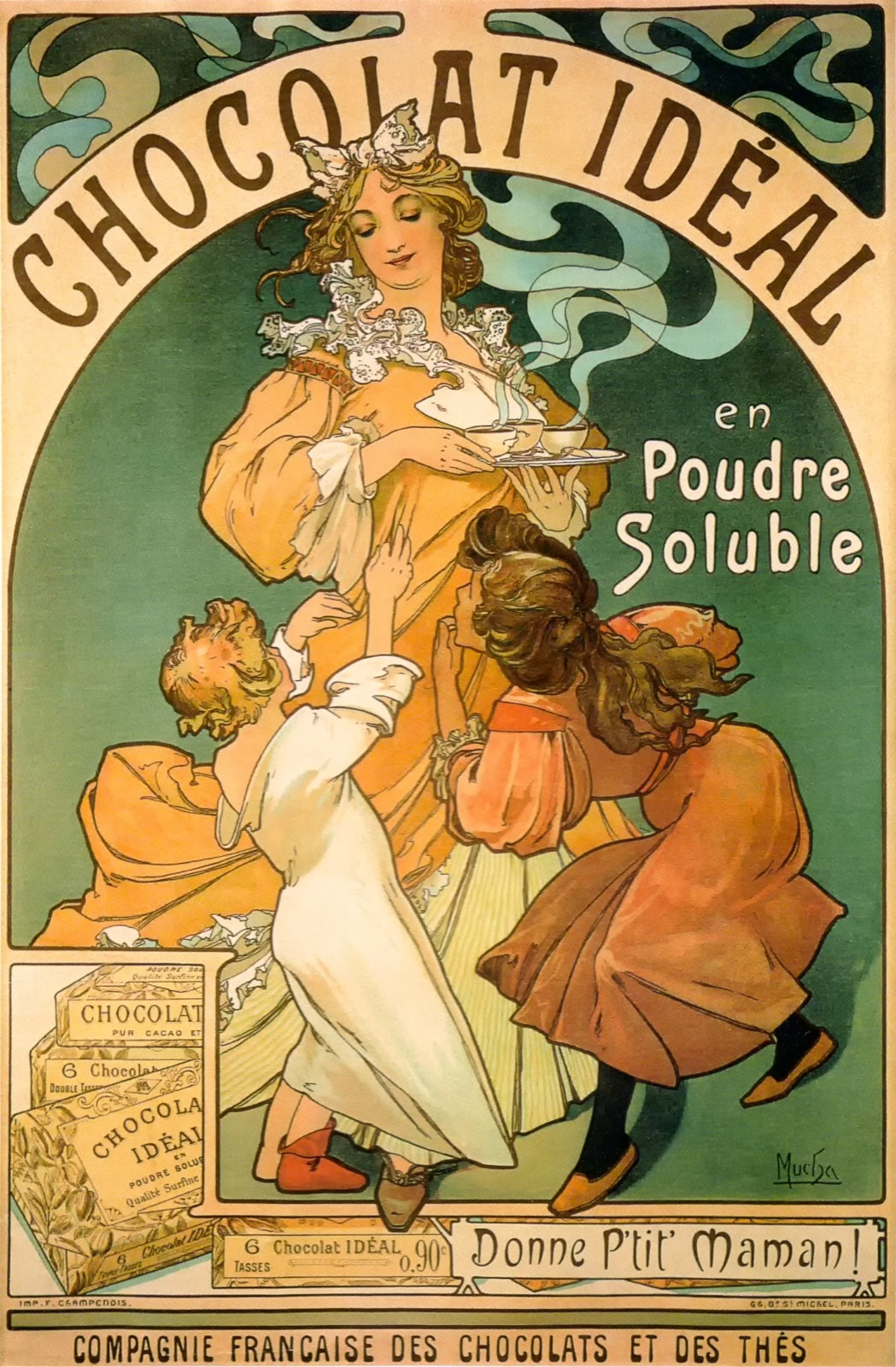

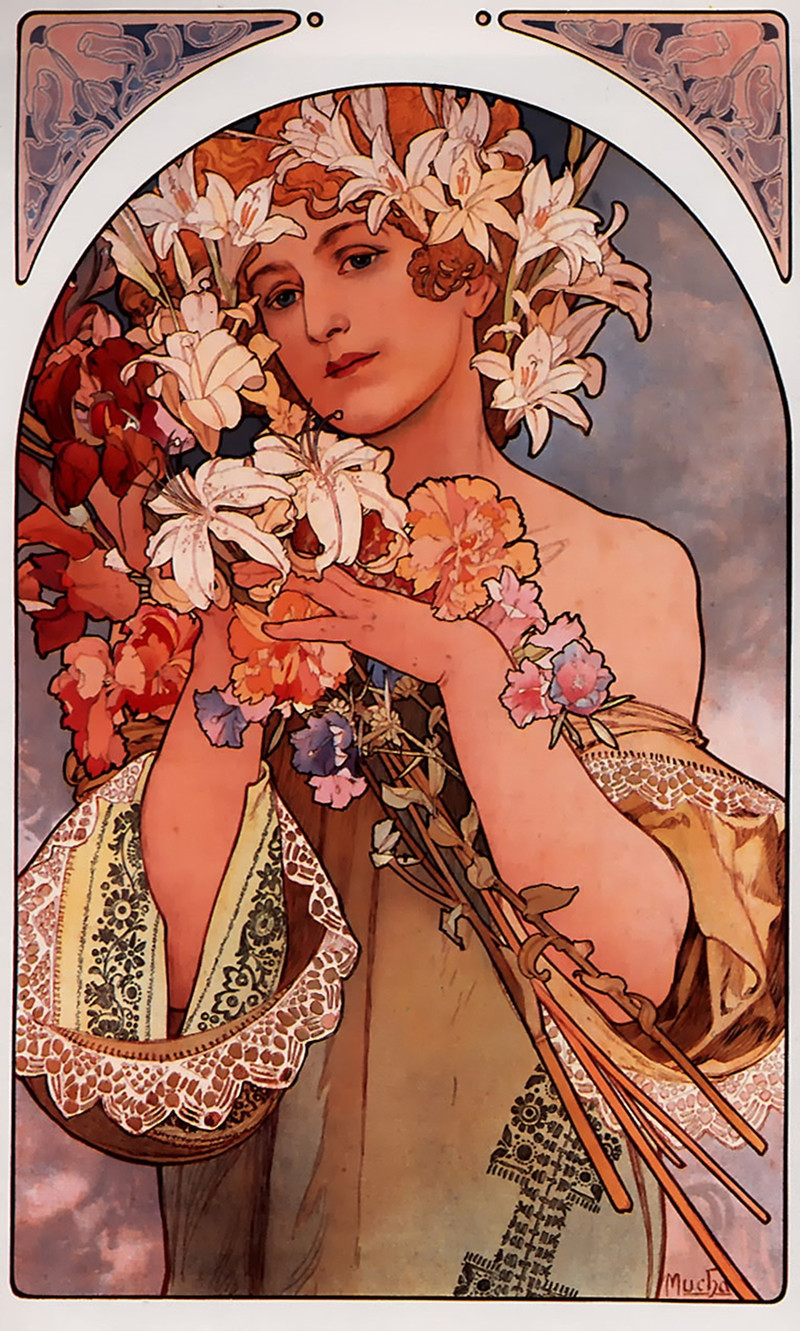

For the next 10 years, Alphonse Mucha kept busy with commissions for posters, book illustrations, programs, and calendars.

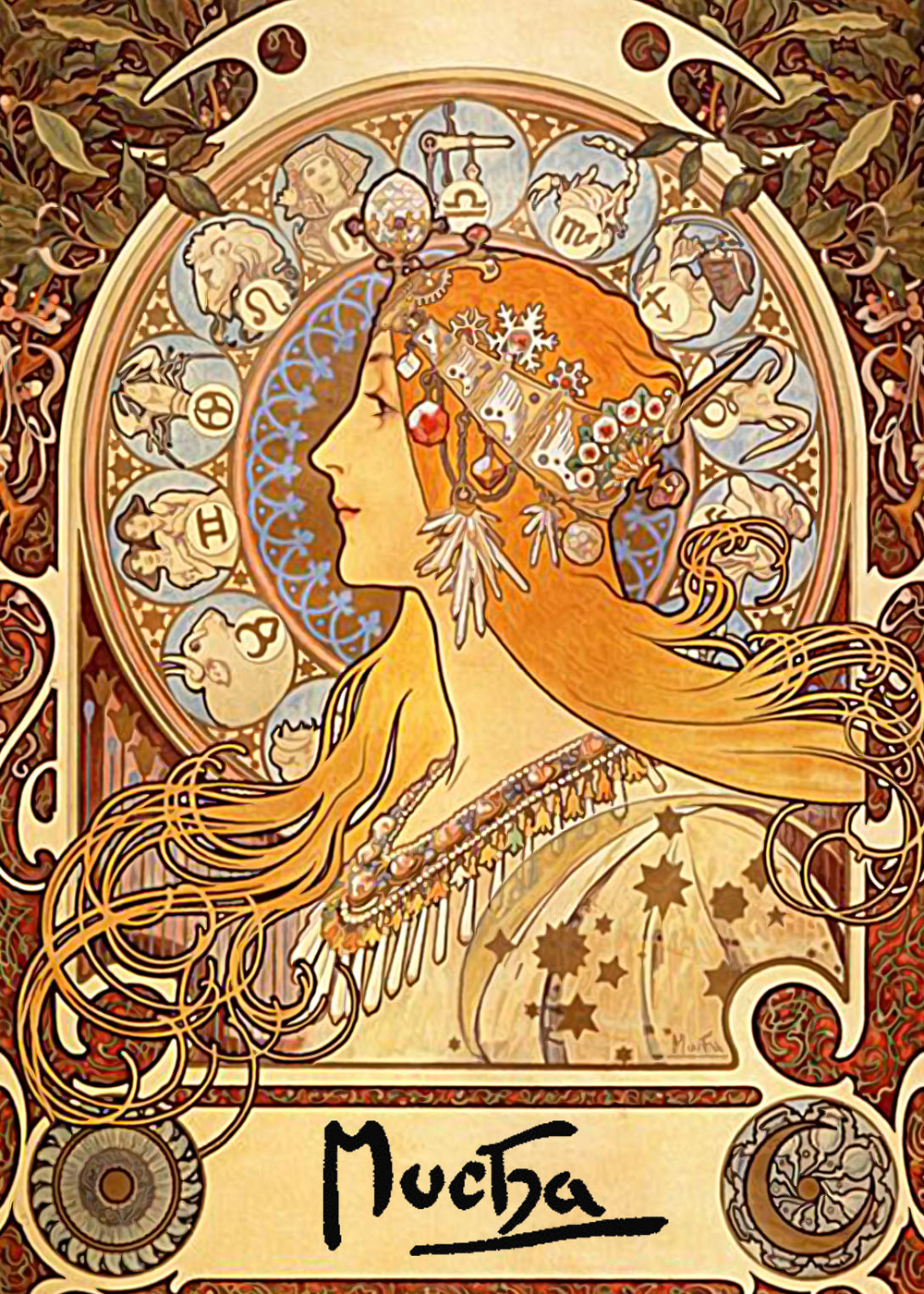

Abounding with ornamental pictorial elements with crisp curvilinear contours, the stylized graceful women of “Style Mucha” became synonymous with the whole Art Nouveau movement.

Mucha’s work captured the worldliness and decadence of the fin de siècle (turn of the century) and the belle époque (“The Beautiful Era”)—a time when Paris was the resplendent cultural capital of the world.

Mucha grew up in a small village in Moravia in what is now the Czech Republic. When he was a boy, it was part of the Habsburg Empire. Poverty and suffering were a part of everyday life—five of Mucha’s brothers and sisters died from tuberculosis.

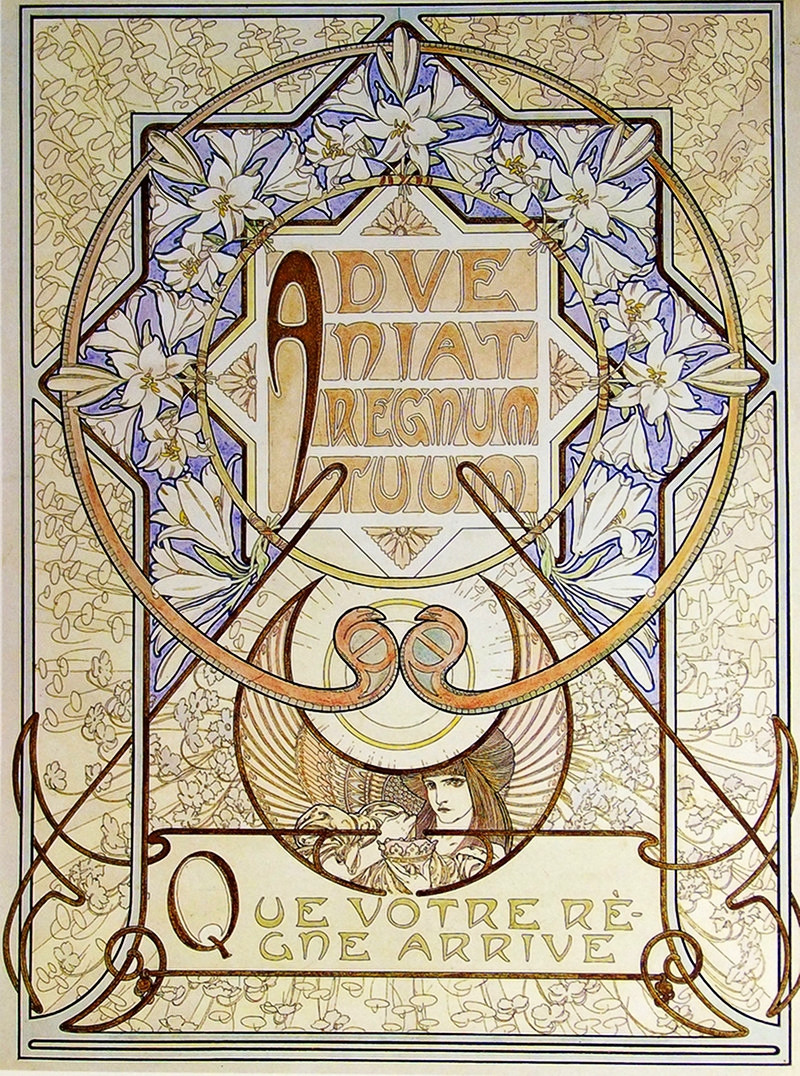

Coming from a deeply religious family, the Church was a big influence on Mucha’s early life. From church decorations to the mysticism of religion, he remained fascinated by spiritualism throughout his life and even dabbled in the occult.

After Paris, Mucha spent four years in the United States before returning to his home country, settling in Prague.

He started work on a fine art masterpiece—a history of the Slavic peoples. Called The Slav Epic, it comprises 20 huge canvases up to 26 ft wide and 20 ft high.

When the Nazis occupied Czechoslovakia in 1939, Mucha was among the first to be arrested. Weakened by interrogation and suffering from pneumonia, he died shortly after being released.

But his art lived on in the hearts of admirers the world over.