After a hard day at the mercy of a corset, 19th-century well-to-do ladies found welcome relief in the tea gown.

Worn for an informal afternoon entertaining friends, or dinner at home with family, the tea gown was a kind of halfway house between a wrapper and a ball gown.

With long sleeves, train, and sumptuous fabrics, they were consummately elegant, yet comfortable too—often being worn with a loose-fitting corset or no corset at all.

1875

The Japanese craze in western art and fashion, and in particular, the Kimono—worn by Japanese women during formal ceremonies—helped shape European tea gowns, which became popular in the United States at around the same time.

1878

1880

By the mid-1880s, tea gowns were considered modish, particularly among followers of the aesthetic movement—believing that life had to be lived intensely, with an ideal of beauty.

One firm catering to this artistic movement was Liberty & Co., famous as the chic venue for exquisite, individualized garments known as “art fabrics from the orient”.

1885

1891

1907

Jacques Doucet was another couturier known for his passion for the refined and exquisite. The House of Doucet’s luxurious offerings were worn by royalty, elite society, and stage actresses.

In the example below, the lace at the bodice adds aesthetic interest, drawing attention to the wearer’s face. The open robe effect’s historical influence creates an air of romantic fantasy.

1920s

The popularity of the tea gown started to wind down in the 1920s, by which time they were very lightweight, with sheer silk and metallic thread.

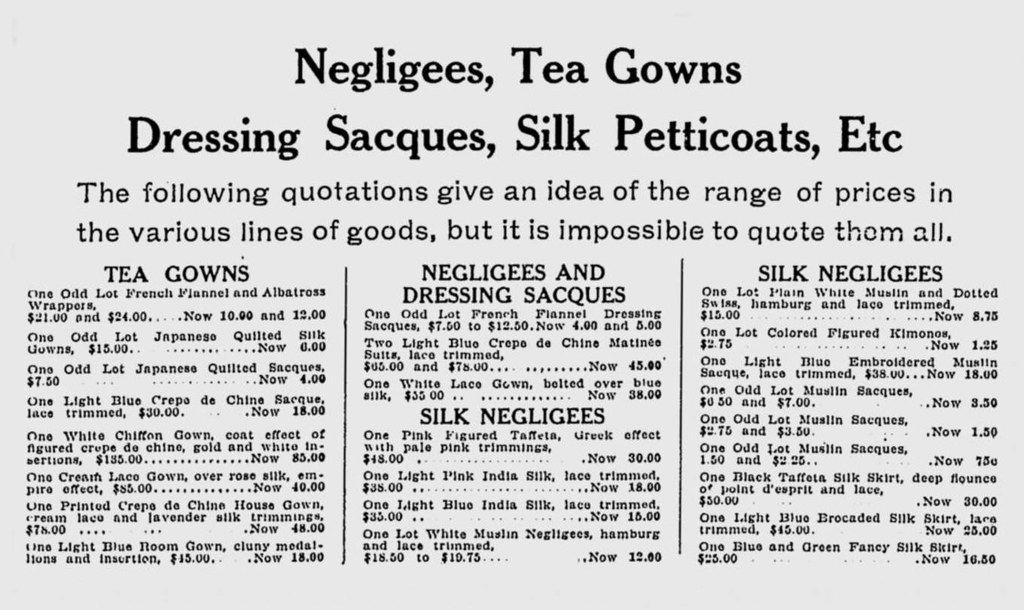

According to the Boston Evening Transcript of 1907, a sale of tea gowns showed list prices varying from (in today’s dollars) about $370 up to $3300.

References

Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Wikipedia.org.

Dress Culture in Late Victorian Women’s Fiction by Dr Christine Bayles Kortsch.

Emily Post (1873–1960): Etiquette, 1922.

Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe by José Blanco F., Patricia Kay Hunt-Hurst, Heather Vaughan Lee, Mary Doering.