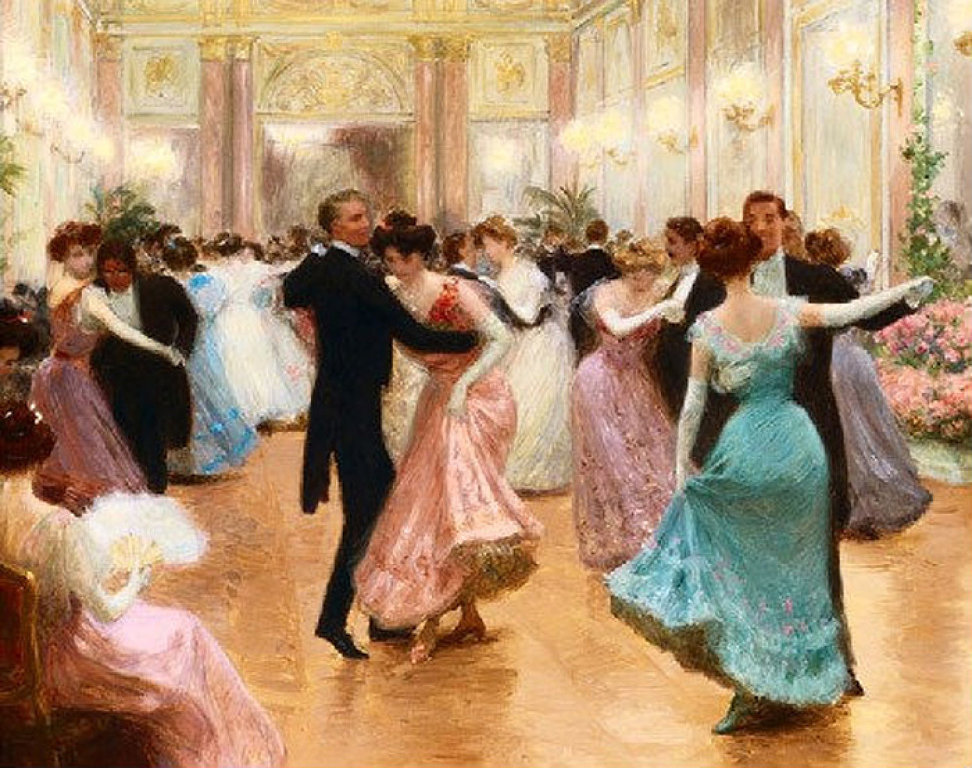

Something wonderful happened to the world of fashion during the second half of the 19th century.

Beautiful gowns were no longer the exclusive privilege of the aristocracy …

… but were available to anyone with the wherewithal to display their finery on the boulevards, in the opera houses, and in café society.

It was a time to “see and be seen”.

And who was responsible for this change?

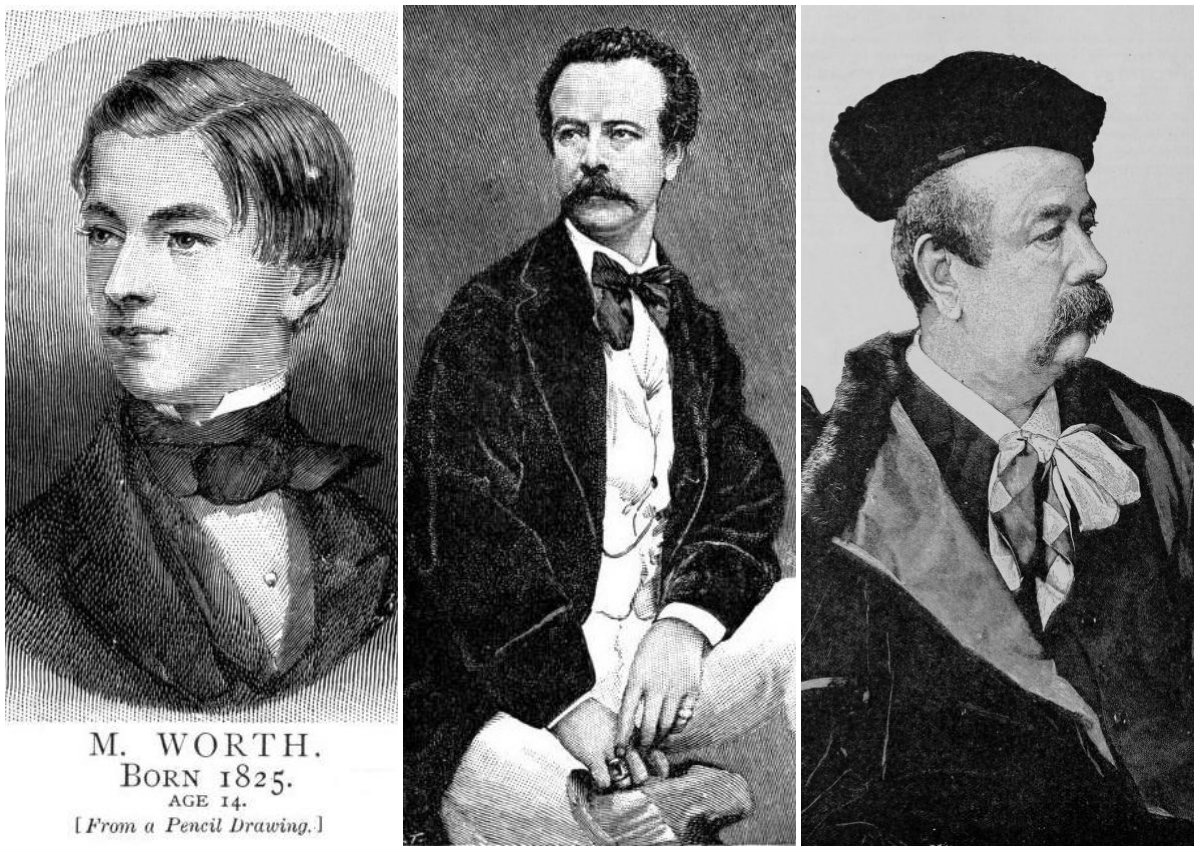

None other than the English entrepreneur Charles Frederick Worth, “the father of Haute Couture”.

Born in Lincolnshire, England, Charles Frederick Worth spent his early career working for department stores and textile merchants in London.

Besides learning all there was to know about fabrics and the dressmaking business, he would spend hours in the National Gallery studying historical portraits.

It was this time in London that would inspire his later works.

As the center of world fashion, Paris beckoned, and Worth found employment with the prominent textile firm Maison Gagelin, soon becoming a leading salesman, then dressmaker.

Establishing a reputation for himself and winning commendations at the expositions in Paris and London, news of Worth’s skills caught the attention of the Empress Eugénie, wife of Emperor Napoleon III of France.

Appointed court designer, Charles Frederick Worth’s success was all but guaranteed.

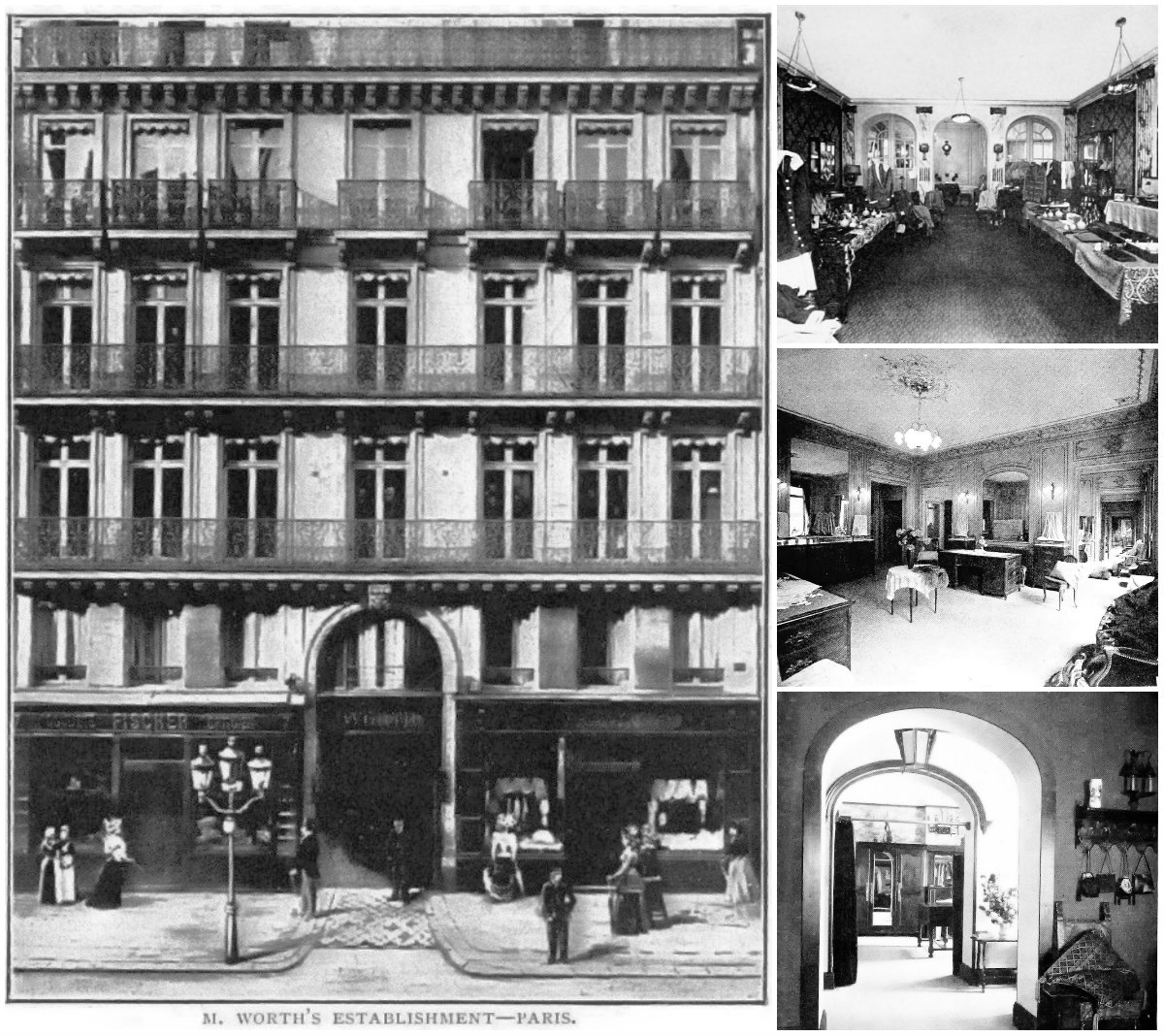

Soon after, he opened his own design house in Paris at 7 Rue de la Paix—first in partnership with Otto Bobergh and later as sole proprietor.

The House of Worth and Haute Couture were born.

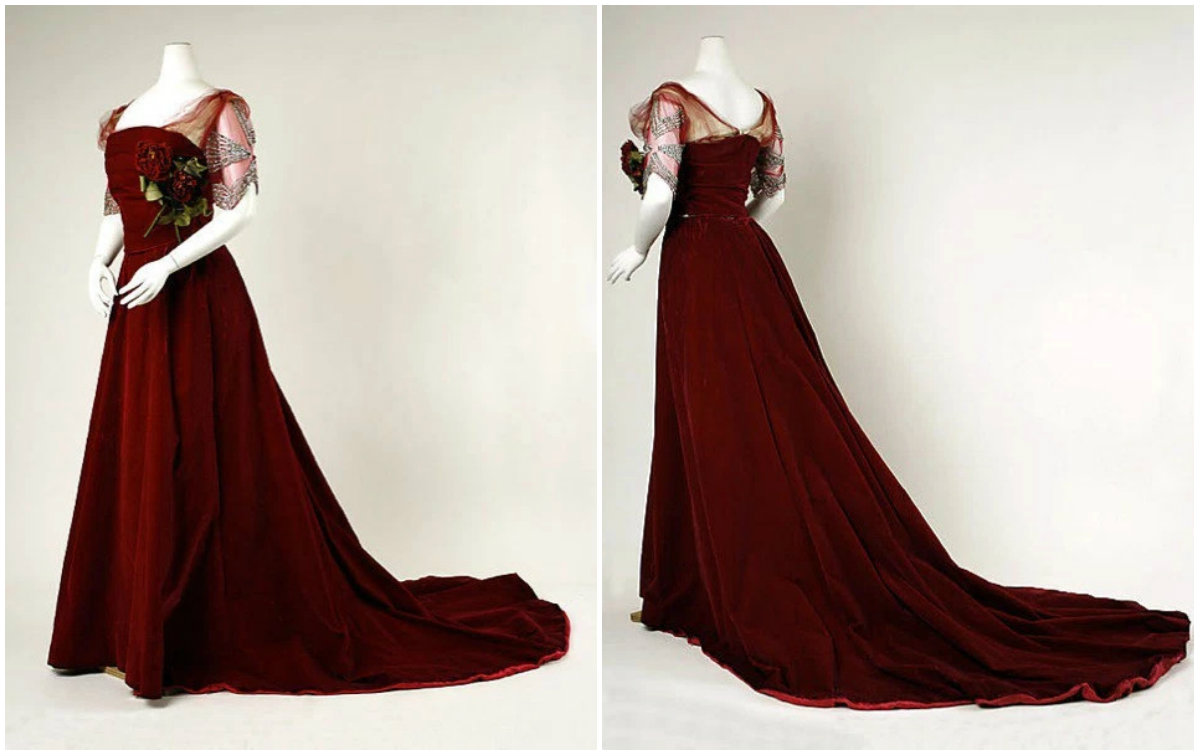

Haute Couture is the fusion of fashion and costume.

It is wearable art.

And wealthy women of the 19th century would pay handsomely for it.

With seemingly endless social engagements, clients changed dress up to four times a day, some purchasing their entire wardrobes from Worth.

The House of Worth was known for showing several designs for each season on live models.

Clients would select their favorites and Worth would tailor-make gowns with elegant fabrics, detailed trimmings, and superb fit.

By the 1870s, Worth’s name frequently appeared in ordinary fashion magazines, spreading his fame to women well beyond courtly circles.

Combining colors and textures using meticulously chosen textiles and trims, House of Worth produced works of art.

That so many examples have survived in such good condition is testament not only to the popularity of Worth among wealthy patrons but also the quality of textiles insisted upon by Charles Frederick Worth.

What better way to celebrate the extraordinary House of Worth than the dulcet tones of Claude Debussy.

This is one of Worth’s earlier designs when he was still in partnership with Otto Bobergh under the name Worth and Bobergh.

Skirts of the 1860s were wide, full, and bell-shaped, supported initially by multiple layers of petticoats and later by crinolines made from graduated hoops of cane or steel.

As the 1870s got underway, the shape of skirts changed, with flatter front and sides and the fullness pulled back and supported behind by a “bustle”.

As the 1880s came to a close, the lines of skirts transitioned away from the bustle to form a clearer shape, but the sleeves swelled to enormous proportions, earning them the nickname “elephant sleeves”.

House of Worth gowns were worn by the very wealthiest of clients. The dinner dress (below left) was worn by the wife of the great American banker J.P. Morgan, Jr.

At night, the stars in the evening dress (below right) would twinkle as the wearer moved and the light caught the different textures.

Charles Frederick Worth passed away in 1895 and The House of Worth remained in operation under his descendents but faced increasing competition from the 1920s onwards, eventually closing in 1956.

The House of Worth brand was revived in 1999 but failed to compete successfully in Haute Couture.