For thousands of years, silk has been a symbol of luxury. Its lustrous finish and soft texture made it the choice of royalty and nobility. The ease with which silk could be worked and dyed earned it the title “queen of textiles”.

Enjoy the story of silk, or click here to advance to the silk fashions of the Georgian, Victorian, Edwardian, and Roaring Twenties eras.

Ancient China

According to Chinese tradition and the writings of Confucius, Empress Leizu, wife of the Yellow Emperor, was enjoying midday tea in her garden under a mulberry tree, when a silk cocoon fell into her tea.

She watched in amazement as a fine thread separated from the cocoon, which she started winding around her finger. Empress Leizu had discovered silk.

One of several stories about the origins of silk, the legend of Leizu dates from the 27th century BC.

Silk’s discovery was kept a closely guarded secret within China for over 2000 years. An imperial decree carried a death sentence for anyone caught exporting silkworms or their eggs.

But one day in the first century AD, a Chinese princess hid silk cocoons in her hair as she left China to marry a prince from the Kingdom of Khotan (near present-day Kashmir). Such was her love for silk that she refused to leave without it.

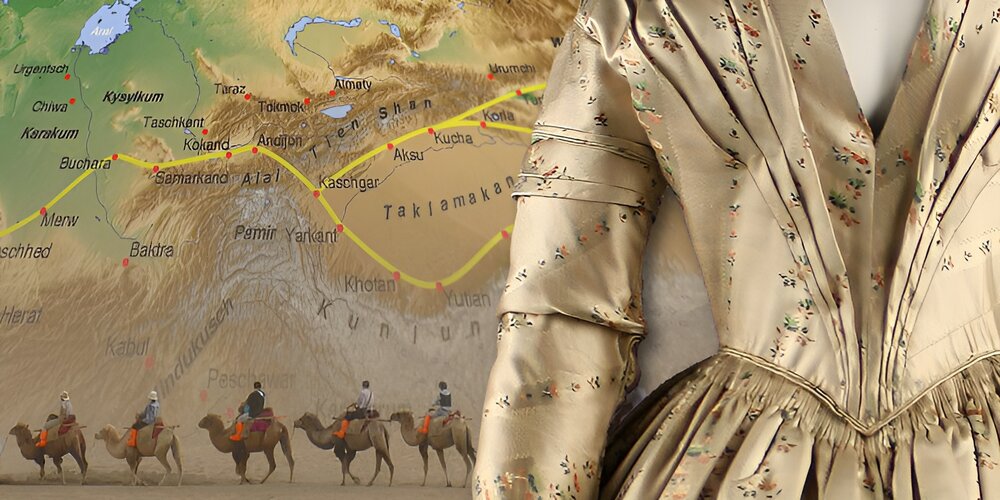

The Silk Road

Khotan became a major stopping point on the Silk Road—an ancient network of trade routes taking its name from the flourishing trade in Chinese silk.

Once the secret of silk was out, China focused on building out trade routes for exporting silk to the West—even extending the Great Wall of China to ensure their protection.

Silk not only accelerated the economic development of Eurasia, but connected East with West along political and cultural lines. Religions, technologies, philosophies, and even diseases all spread along the Silk Road.

Shimmering Silk

Silk was a sign of great wealth in China and became such a mania among high society that its use was subsequently limited to just the imperial family.

Its highly prized natural shimmer comes from the triangular structure that refracts light like a prism. And with good absorbency, it dyes easily.

Although silk was gradually allowed to be worn by other classes of society, Chinese peasants were excluded until 1644.

As China grew rich from the silk trade, neighboring territories looked on through envious eyes. Silk was used as a diplomatic offering to pacify raiding tribes and also to pay China’s own soldiers, who traded it for furs and horses from nomadic peoples at the gates of the Great Wall.

A Symbol of Luxury

The Romans perceived silk as a symbol of decadence and immortality.

Justinian, Emperor of the Byzantine Empire, wanted more than merely trading silk with the Chinese—he wanted to develop his own silk industry.

He sent two monks to China to smuggle silkworm eggs out of the country in hollow bamboo rods.

Byzantine silks became known for their meticulous attention to detail and fine decoration.

After the Siege of Constantinople in 1204, the Byzantine silk industry declined and 2000 skilled weavers left for Italy.

And so began a booming Italian silk industry, with the cities of Lucca, Genoa, Venice, and Florence supplying the luxury demands of a growing bourgeoisie across Europe.

Driven by the demand for luxury French fashions, France developed its own silk industry, overtaking Italy as the capital of the European silk trade.

Technological Advancements

Silk and the textile industry were the driving force behind technological change in the 13th and 14th centuries. Bobbins and warping machines were introduced, as was the button loom of Jean le Calabrais.

But the biggest changes of all came with the Industrial Revolution.

On the eve of the Industrial Revolution, spinning and weaving were largely cottage industries. Two inventions were about to change a way of life that had existed for centuries and usher in the rise of textile factories and mass production.

An early forerunner to modern-day computers, Joseph Marie Jacquard’s 1801 invention of a programmable loom (the “Jacquard loom”) simplified weaving of complex patterns for brocade, damask, and matelassé.

Power looms boosted worker output by a factor of 40 and by the mid-19th century there were 260,000 in operation in England alone.