Today, furniture fills our living and working spaces. It makes a statement about our taste for practicality and aesthetics.

But it wasn’t always so.

At the beginning of the 18th century, only the aristocracy or merchant class could afford furniture as luxurious expressions of individuality.

Then from around 1760, something remarkable happened. The standard of living for the general population began to increase for the first time in history.

This was the dawn of the industrial revolution and the beginnings of what would become a consumer society.

18th-century luminary Sir Joshua Reynolds observed a general progression from buying basic needs to purchasing more luxurious goods.

In this statement was implied the increasing importance of design, which simultaneously created and followed taste, and in so doing, helped stimulate consumer demand and foster economic stability.

Perhaps no other industry demonstrated this better than furniture making. And what piece of furniture was more prominent than a sofa?

The Georgian Era

Some think of the Georgian era as the golden age of furniture.

The drama and exuberance of Baroque, the intricate asymmetrical patterns of Rococo, the graceful lines, sensuous curves, and elegant proportions of Neo-Classical—all helped define Georgian era furniture.

The very names of the period are synonymous with timeless quality—Queen Anne, Chippendale, Sheraton, Hepplewhite.

Sofas with a wide central section and a single outward-facing seat at each end were called a canapé à confidents and were meant to be where people could share confidences.

Examples were made primarily in the Louis XV and Louis XVI periods, highly decorative, and the shape and carving were designed to harmonize with the wall paneling.

The artisan’s skill shows particularly in the carving of roses and olive branches tied by a ribbon at the top of each end.

This piece was described by comte de Salverte as the finest of its kind in the Louis XVI style.

The Regency and Federal Era

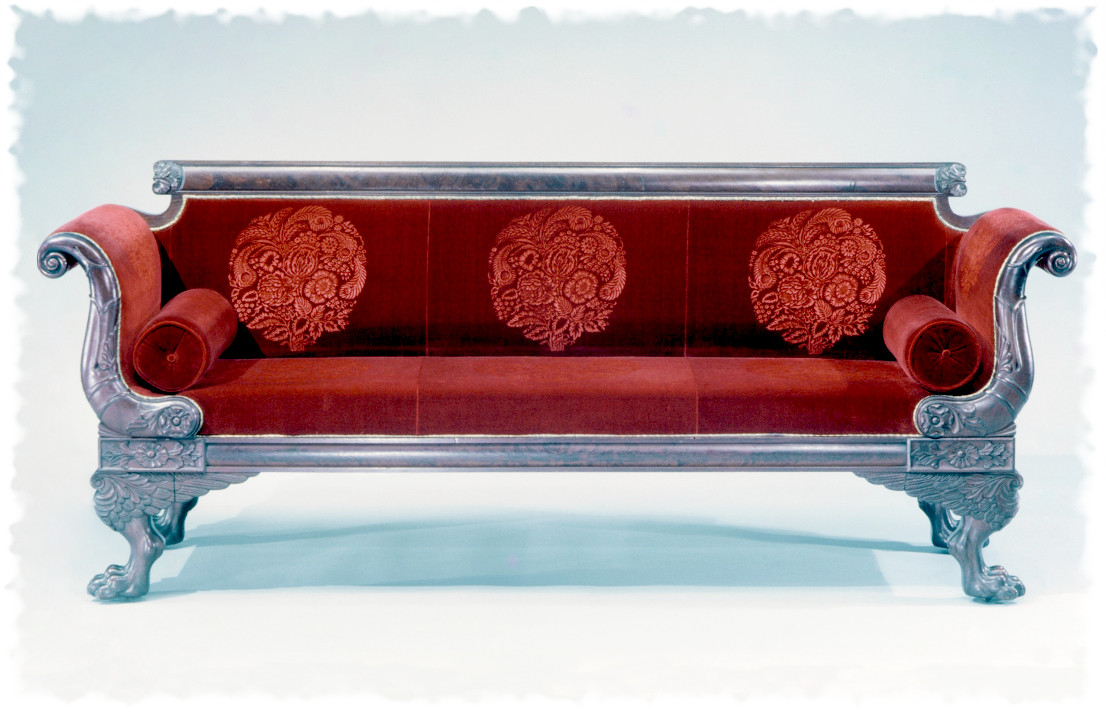

Roughly coinciding in date and style, the British Regency and American Federal styles were defined by a lighter, more delicate interpretation of the classical Greek and Roman influences.

The shape of this sofa derives from plate 35 in Thomas Sheraton’s “Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book” (1793).

The modern black horsehair and gilded tacks of this scroll-back sofa help define it as the classic New York form as it would have looked when it first came out of the workshop.

A highly sophisticated blend of line, detailed carving, and subtle color merge with antique legs in the shape of dolphins, hinting at the maritime influences of the time. In Greek mythology, dolphins swam to the aid of shipwrecked sailors.

Owned by Thomas Cornell Pearsall, a wealthy New York merchant and shipowner, the skillful execution of the details derives from Greco-Roman seating forms illustrated and described in the 1808 supplement to the London “Chairmakers’ and Carvers’ Book of Prices.”

Noteworthy in this design is the unusual trimming of rich stamped brass, rather than the woven galloon or series of brass-headed nails that were customary in this period.

Italian architect Filippo Pelagio Palagi designed this set of furniture for the principal drawing room next to the royal bedroom of Carlo Alberto, king of Sardinia.

The sculptural detail of the crest rails and the quality and refinement of the veneering help distinguish this sofa, made by Gabrielle Cappello, whose workshop produced many of Pelagi’s designs.

The Victorian Era

With the Victorians, out went the simpler classical lines of Georgian and Regency and in came a more imposing style, with elaborate decoration, heavily carved pieces, plenty of organic curves inspired by nature and glossy finishes.

This sofa is part of a suite of Louis XVI–style furniture that railroad executive John Taylor Johnston (1820–1893) purchased in about 1856 and used in the music room of his residence at 8 Fifth Avenue.

Exemplifying the Rococo Revival style, which was popular in America during the 1840s and 1850s, the sofa below combines curvilinear forms reminiscent of 18th-century France with the exuberant, naturalistic ornamentation of the mid-Victorian period.

Distinguished by a voluptuous serpentine crest with luxuriant, griffin-flanked bouquets, the central floral garland is supported by a Renaissance-style urn and paired dolphins.