1. Chinoiserie was once the most coveted fashion of the aristocracy

During the 17th and 18th centuries, Europeans became fascinated with Asian cultures and traditions. They loved to imitate or evoke Asian motifs in Western art, architecture, landscaping, furniture, and fashion.

China seemed a mysterious, far-away place and the lack of first-hand experiences only added to the mystique.

Chinoiserie derives from the French word chinois, meaning “Chinese”, or “after the Chinese taste”. It is a Western aesthetic inspired by Eastern design.

To immerse yourself in the Chinoiserie experience, optionally play the traditional East Asian music.

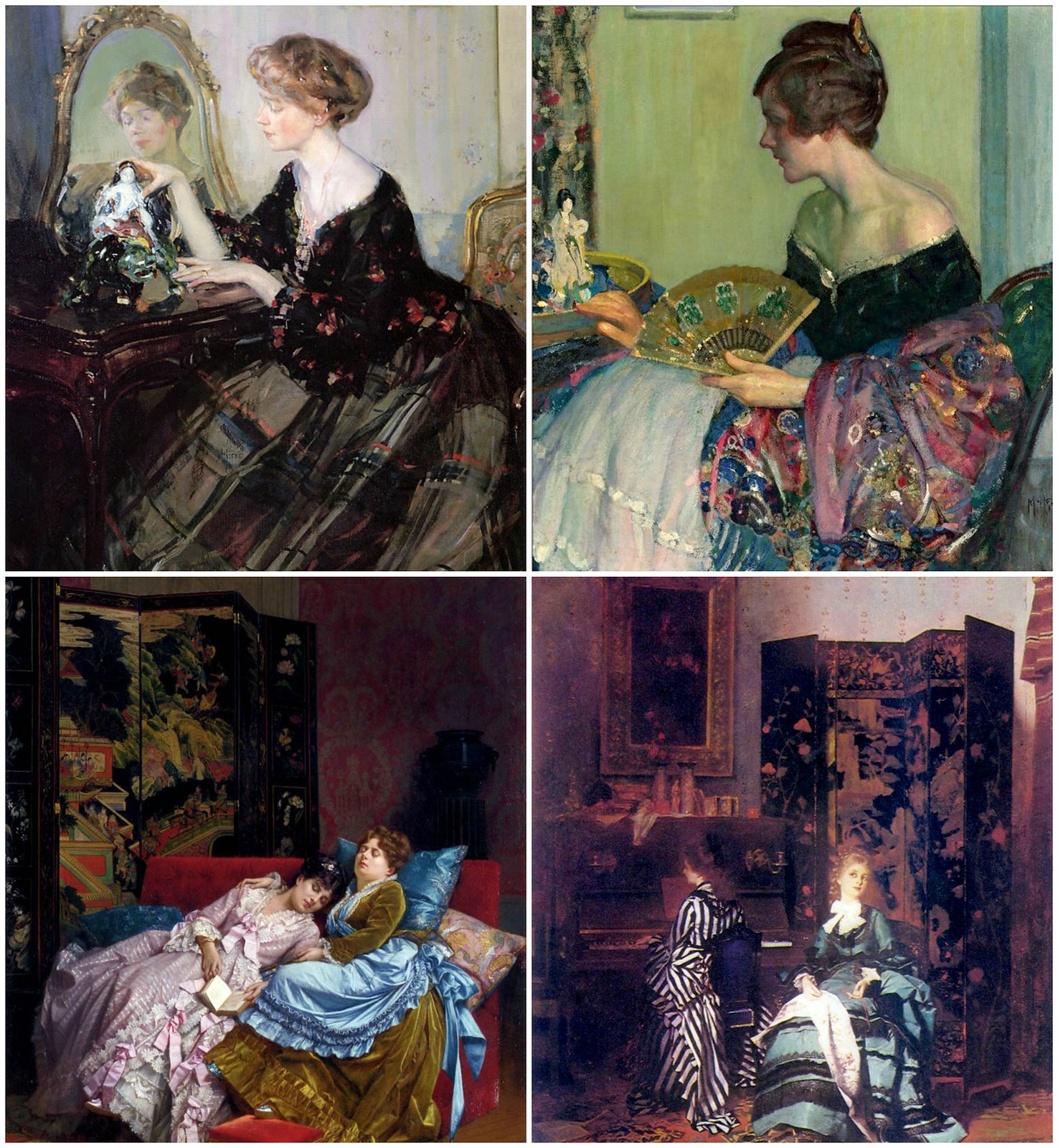

A folding screen was one of the most popular expressions of Chinoiserie, often decorated with beautiful art.

Themes included mythology, scenes of palace life, nature, and romance in Chinese literature—a young lady in love could take a curious peek hidden from behind a folding screen.

2. Chinoiserie’s popularity grew with rising trade in the East

Rising trade with China and East Asia during the 17th and 18th centuries brought an influx of Chinese and Indian goods into Europe aboard ships from the English, Dutch, French, and Swedish East India Companies.

By the middle of the 19th century, the British East India Company had become the dominant player in East Asian trading, its rule extending across most of India, Burma, Malaya, Singapore, and British Hong Kong.

A fifth of the world’s population was under the trading influence of the British East India Company.

3. Chinoiserie began with tea drinking

Drinking tea was the height of fashion for ladies of good taste and required an appropriate chinoiserie mise en scène.

Tea and sugar were expensive commodities during the eighteenth century and this chest could be locked to secure its valuable contents.

Containing two canisters for tea (green and black) and a larger one for sugar, the pastoral scenes, and Italianate landscapes, combined with Rococo gilding against a pink ground, create an opulent effect.

4. Aristocratic women were famous collectors of chinoiserie porcelain

Among them were Queen Mary, Queen Anne, Henrietta Howard, and the Duchess of Queensbury—all socially important women, whose homes served as examples of good taste and sociability.

Wealthy women helped define the prevailing vogue through their purchasing power. One story tells of a keen competition between Margaret, 2nd Duchess of Portland, and Elizabeth, Countess of Ilchester, for a Japanese blue and white plate.

Reflecting the English factory’s focus on Asian porcelains as a primary source of inspiration, this plate with its skillfully composed chinoiserie decoration, is an ambitious work from the 1750s, the decade during which Bow first achieved commercially viable production.

Distinguished by the chinoiserie scenes painted by Charles-Nicolas Dodin, these elephant vases from c. 1760 are thought to have been commissioned by Mme. de Pompadour, chief mistress of Louis XV of France. They are among the rarest forms produced by the famous Sèvres manufactory in the suburbs of Paris.

5. Chinoiserie is related to the Rococo style

Both styles are characterized by exuberant decoration, a focus on materials, stylized nature, and subject matter depicting leisure and pleasure.

Exotic chinoiserie accents in the pagoda-shaped outline of the tureen’s lid exemplify an interpretation popular in southern Germany.

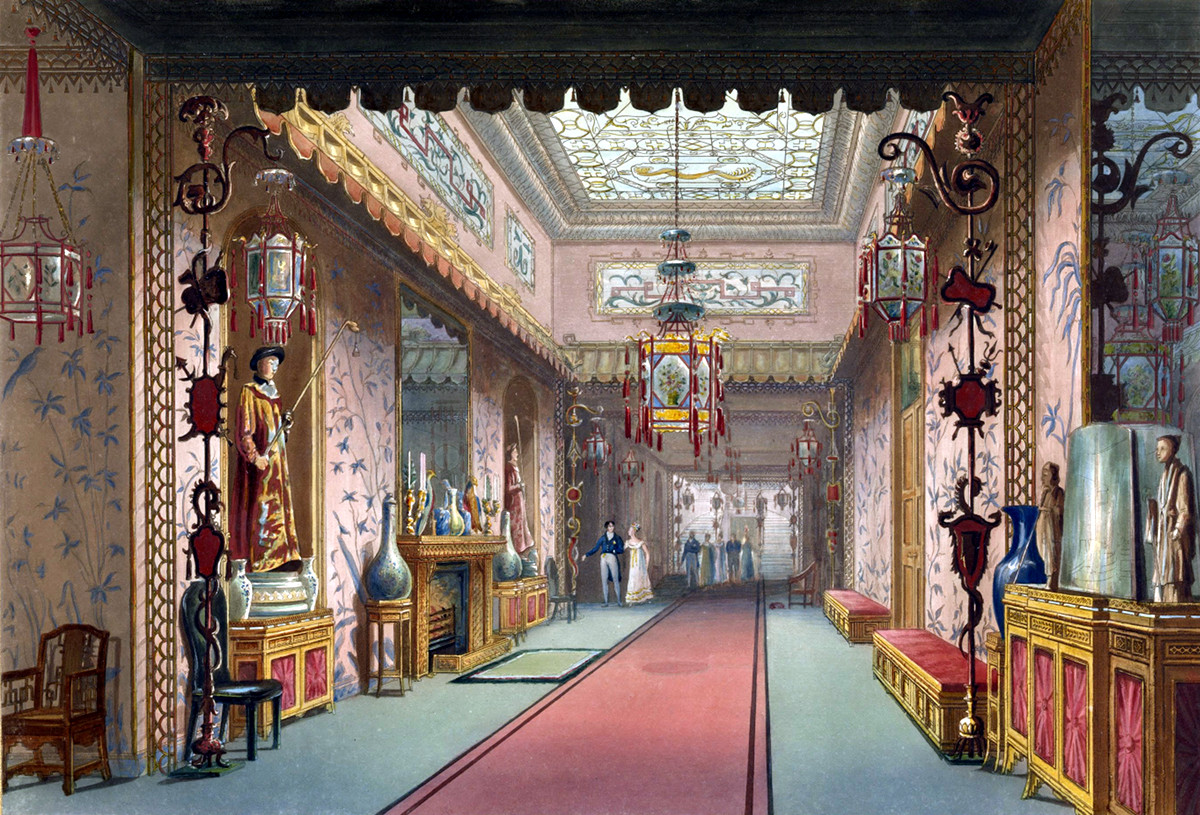

6. European monarchs gave special favor to Chinoiserie

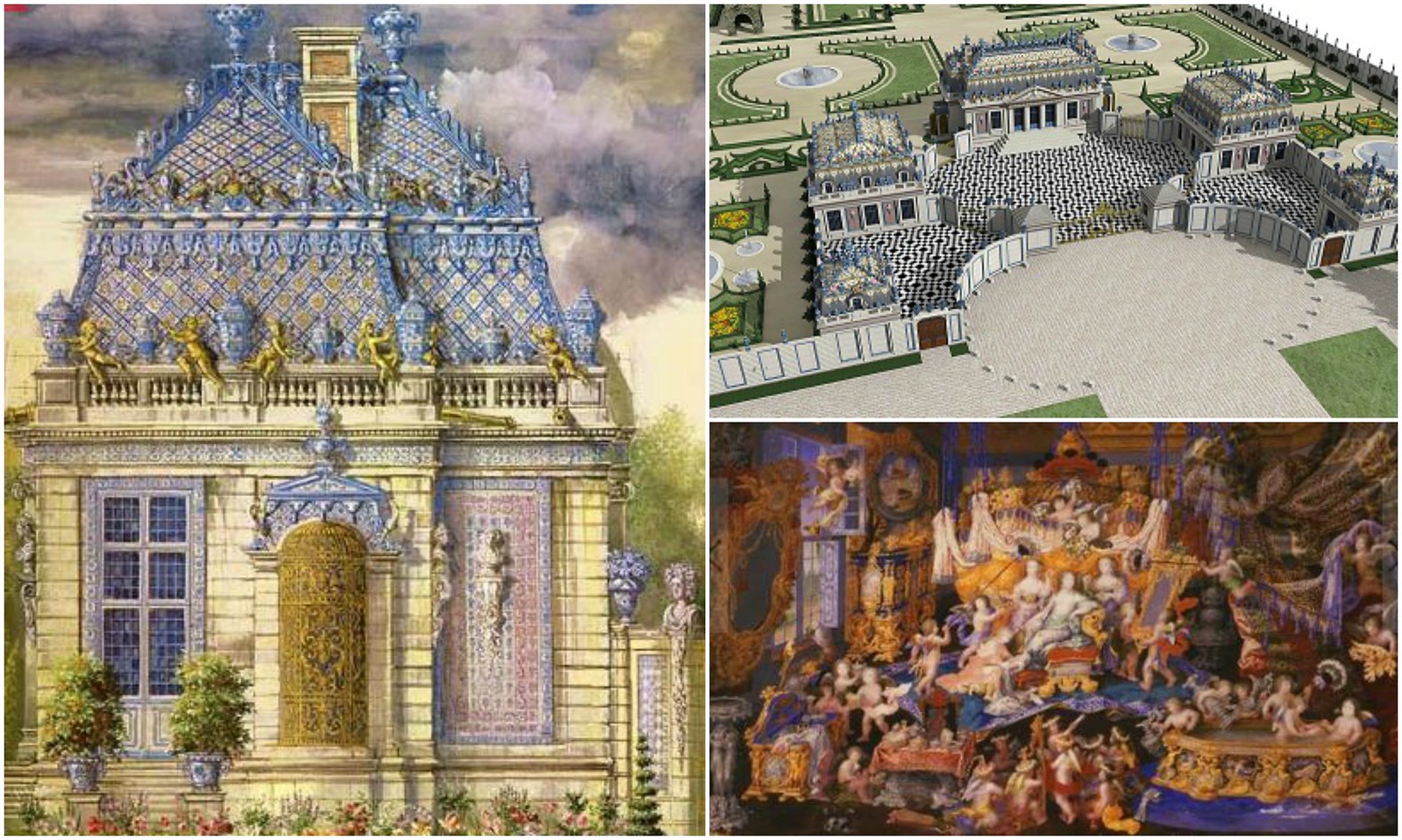

King Louis XV of France and Britain’s King George IV thought Chinoiserie blended well with the rococo style.

Entire rooms, such as those at Château de Chantilly, were painted with chinoiserie compositions, and artists such as Antoine Watteau and others brought expert craftsmanship to the style.

Highly ornamental, yet elegant, Western interpretations of Eastern themes were fanciful expressions, often with exotic woods and marbles used to further the effect.

Built in 1670 at Versailles as a pleasure house for King Louis XIV’s mistress, the Trianon de Porcelaine was considered to be the first major example of chinoiserie. It was replaced by the Grand Trianon 17 years later.

Frederick the Great, King of Prussia had a Chinese House built in the gardens of his summer palace Sanssouci in Potsdam, Germany.

Garden architect Johann Gottfried Büring designed the pavilion in the style of Chinoiserie by blending Chinese architectural elements with ornamental rococo.

7. Europeans manufactured imitations of Chinese lacquer furniture

Frequently decorated with ebony and ivory or Chinese motifs of pagodas and dragons, Europeans such as Thomas Chippendale helped popularize Chinoiserie furniture.

Chippendale’s design book The Gentleman and Cabinet-maker’s Director: Being a large Collection of the Most Elegant and Useful Designs of Household Furniture, In the Most Fashionable Taste provided a guide for intricate chinoiserie furniture and its decoration.

8. Marco Polo was the first European to describe a Chinese garden

Marco Polo visited the summer palace of Kublai Khan at Xanadu in around 1275.

Evolving over three thousand years, the Chinese garden landscaping style became popular in the West during the 18th century.

Built in 1738, the Chinese House within the gardens of the English Palladian mansion at Stowe in Buckinghamshire, was the first of its kind in an English garden.

Hundreds of Chinese and Japanese Gardens were built around the world to celebrate the naturalistic, organic beauty of their asymmetric design.

9. Wealthy gentlemen preferred Banyans to formal clothing

Made from expensive silk brocades, damasks, and printed cottons, banyans were types of dressing gown with a kimono-like form and Eastern origin. Worn with a matching waistcoat and cap or turban, they were so popular among wealthy men of the late 18th century that they posed for portraits wearing the banyan instead of formal clothing.

10. Chinoiserie enjoyed a renaissance in the 1920s and 1930s

Intimating the most elaborate past of the Chinese court, the Chinoiserie roundels of this Lanvin robe de style alternately resemble embroidered Manchu court badge motifs or the glinting scales of Mongol armor interpreted in Western embroidery.

Stressing tubular simplicity, Callot Soeurs used the reductive rubric of Art Deco to combine Chinoiserie with other styles, resulting in an intoxicating fusion of exoticisms.

Known for their Chinoiserie, Callot Soeurs also featured the long fluid vestigial sleeves of Ottoman coats.

References

Wikipedia

V&A Museum

The Met

The British Museum