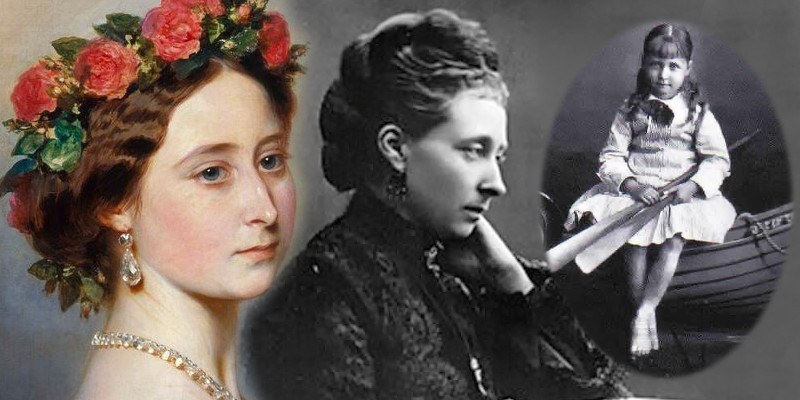

Princess Alice, the second daughter of Queen Victoria, didn’t lead the charmed life of many 19th-century princesses.

After she died, the Times of London wrote:

This is the tragic story of the princess who died from a kiss.

Happy beginnings

Our story begins in England in 1840, when the young Queen Victoria meets the love of her life—a German prince named Albert.

That they were happy was never in doubt, as Victoria’s own letters and diary entries attest:

On the evening of their wedding day, 10 February 1840, Victoria wrote:

With such a match made in heaven, one would imagine all of Victoria’s children living charmed, blissful lives.

But fate had other plans.

Favorite name

The first of nine children—also named Victoria—arrived on 21 November, 1840.

But it was the arrival of their third child and second daughter, Alice on 25 April 1843, where our story starts to unfold.

Alice was named in honour of Victoria’s first Prime Minister and mentor, Lord Melbourne, who had said the name “Alice” was his favorite for a girl

A happy day tinged with sadness

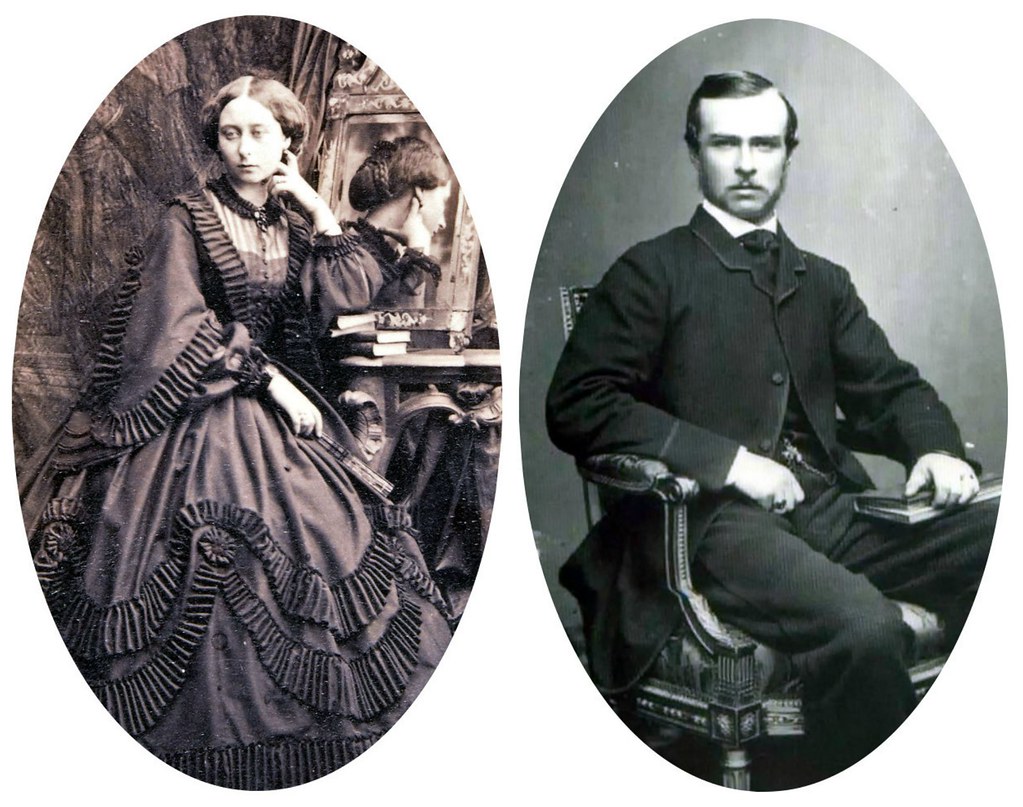

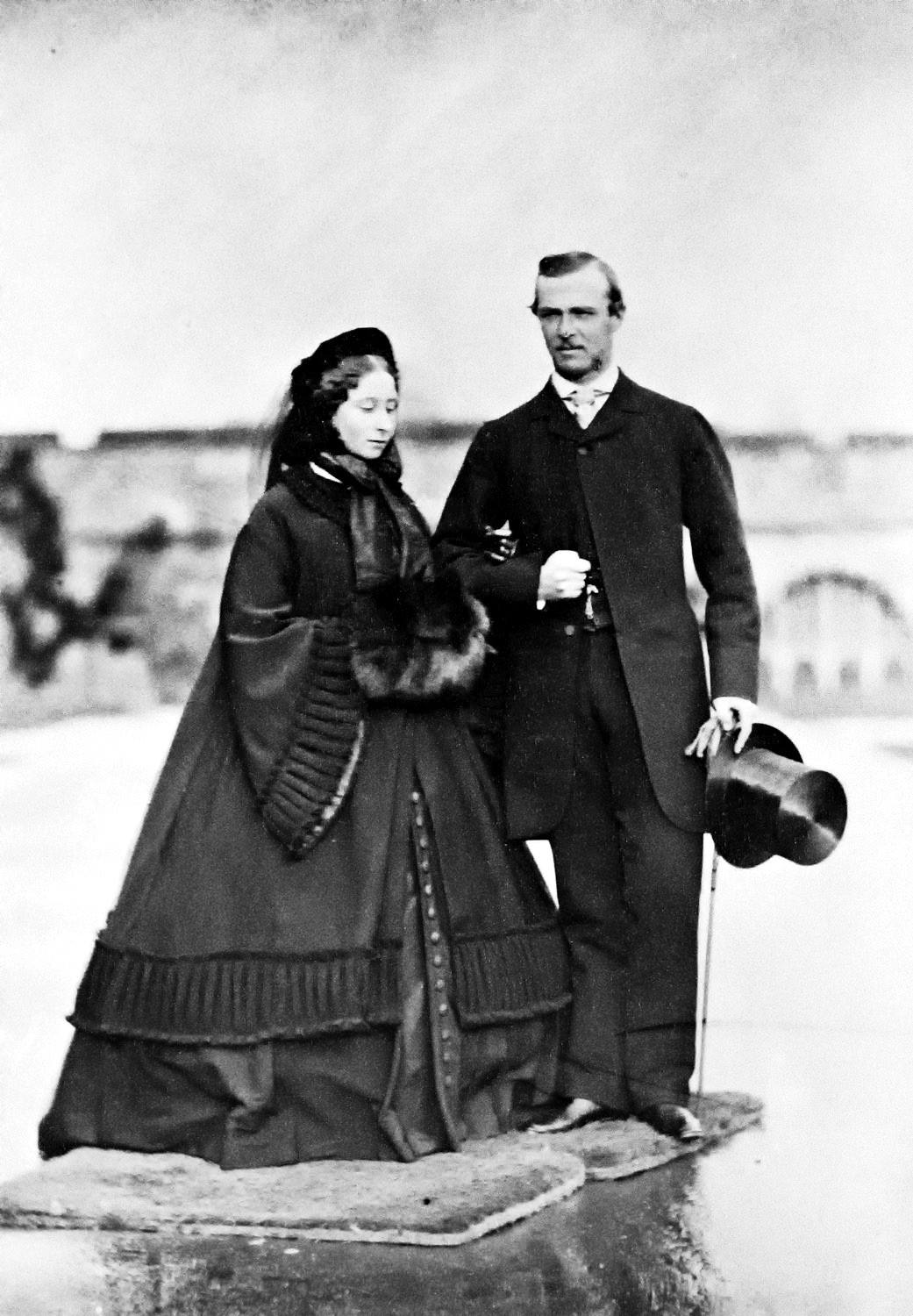

At the suggestion of her older sister, Victoria, she became engaged to a handsome German Prince, Louis of Hesse, in April of 1861.

They planned to marry on 1 July the following year.

But six months before the wedding, tragedy struck.

On 14 December 1861, her father, Prince Albert, died.

Despite her mother’s grief and the royal family still being in deep mourning, the wedding went ahead as planned.

But although Alice wore a white dress for the ceremony, she had to wear black mourning clothes before and after.

Unlike her sister Victoria, who would become Queen of Prussia through her marriage to German Emperor Frederick III, Alice’s home in the little city of Darmstadt, Hesse, in what is now Germany, was far more modest.

Although Queen Victoria expected a new palace would be built for the newlyweds, the people of Darmstadt had different ideas.

So Louis and Alice settled on a house in Darmstadt’s “Old Quarter”, overlooking the street.

Rumbling carts and street noise could be heard through the thin walls, but Alice liked her surroundings and started taking painting lessons from a local artist.

Alice’s compassion for the suffering of others was well-known within the royal family.

When her grandmother fell ill from a severe infection, Alice nursed and comforted her in her final hours—just as she had done for her father.

And Alice was there to comfort her distraught mother, becoming her unofficial secretary for the next six months.

When war broke out between Austria and Prussia and her husband had to join the conflict on the side of Austria, she dutifully went to work making bandages for troops and preparing hospitals, despite being pregnant with her third child.

A fateful fall

It wasn’t long before more painful tragedy would befall Alice.

In 1873, her youngest and favourite son Friedrich, called “Frittie”, died after falling from a window.

Little Frittie’s hemophilia meant that bleeding from his internal wounds could not be stopped.

Alice never recovered from his death.

Beside herself with grief, she wrote to her mother, Queen Victoria, for some solace.

But it was a time of anxiety for the Queen. She was not to be disturbed.

Victoria was trying to pair her son Prince Alfred with the Russian Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna, but the Russians had refused to send her to England for “pre-marriage inspection”.

Instead, they invited Queen Victoria to meet the family in Germany, which Alice thought was a wonderful idea.

Lesson #1: timing was everything when dealing with Queen Victoria, no matter who you were.

Her mother sent a scathing letter:

So much for seeking comfort.

The Kiss of Death

Alice dedicated herself to Ernest, her only surviving son, and her newborn daughter Marie.

But she suffered ill health from the stresses of her duties and retreated to Balmoral Castle hoping the fresh air of Scotland would help her recover.

Shortly after her return in November of 1878, a diphtheria epidemic swept through Darmstadt and hit the royal household hard.

All of her children except Elisabeth, who was staying with her paternal grandmother, became infected, as did her husband.

So swift was the disease once it had taken hold, that when Alice was called to the bedside of her daughter Marie, by the time she arrived, Marie had already choked to death.

Highly contagious, the family had to be contained in separate bedrooms, and Alice kept the news of Marie’s death from her children for several weeks.

Until one day in December, when she knew she had to break the awful news to her son, Ernest.

Devastated, Ernest refused to believe it and sobbed uncontrollably.

At that moment, the hand of fate dealt Alice a life-threatening blow.

Out of concern for Ernest’s grief, she comforted him with a kiss.

At first, nothing happened.

She met her sister as she was passing through Darmstadt on her way to England, and even wrote a more cheerful letter to her mother.

Then on 14 December—the exact date of her father Albert’s death—the symptoms of diphtheria took hold and extinguished her life.

Her last words were “Dear Papa”.

Why is fate so cruel? And why do the nicest, warmest, and kindest people suffer?

It is one of life’s great mysteries.

What history teaches us is that we are never alone in our grief—many others have come before us.

We are all connected through time.