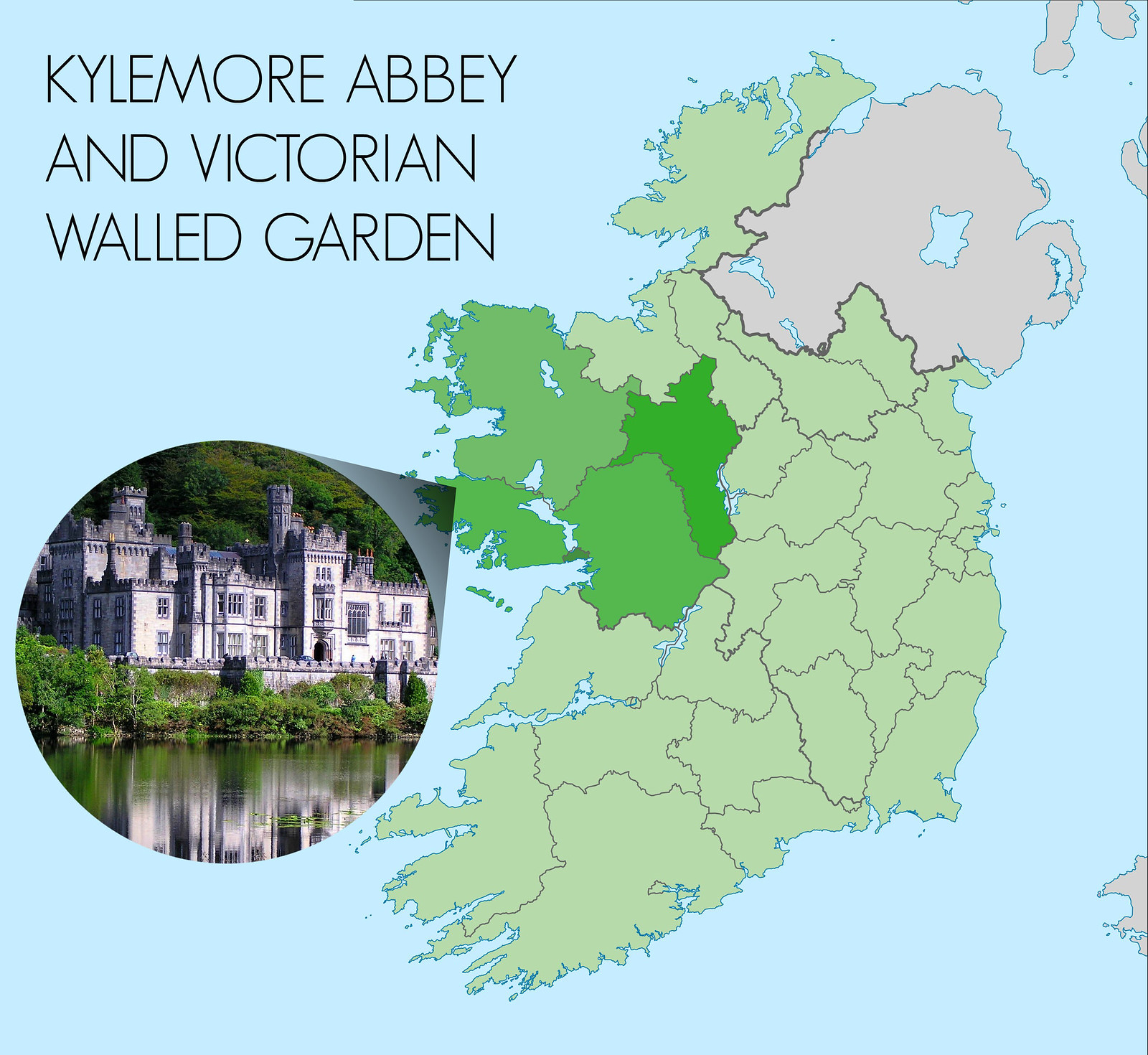

The year was 1871. Wealthy financier and Member of Parliament Mitchell Henry (1826 – 1910) was standing with his wife on the shores of a lake in County Galway, Ireland, admiring their new fairytale castle.

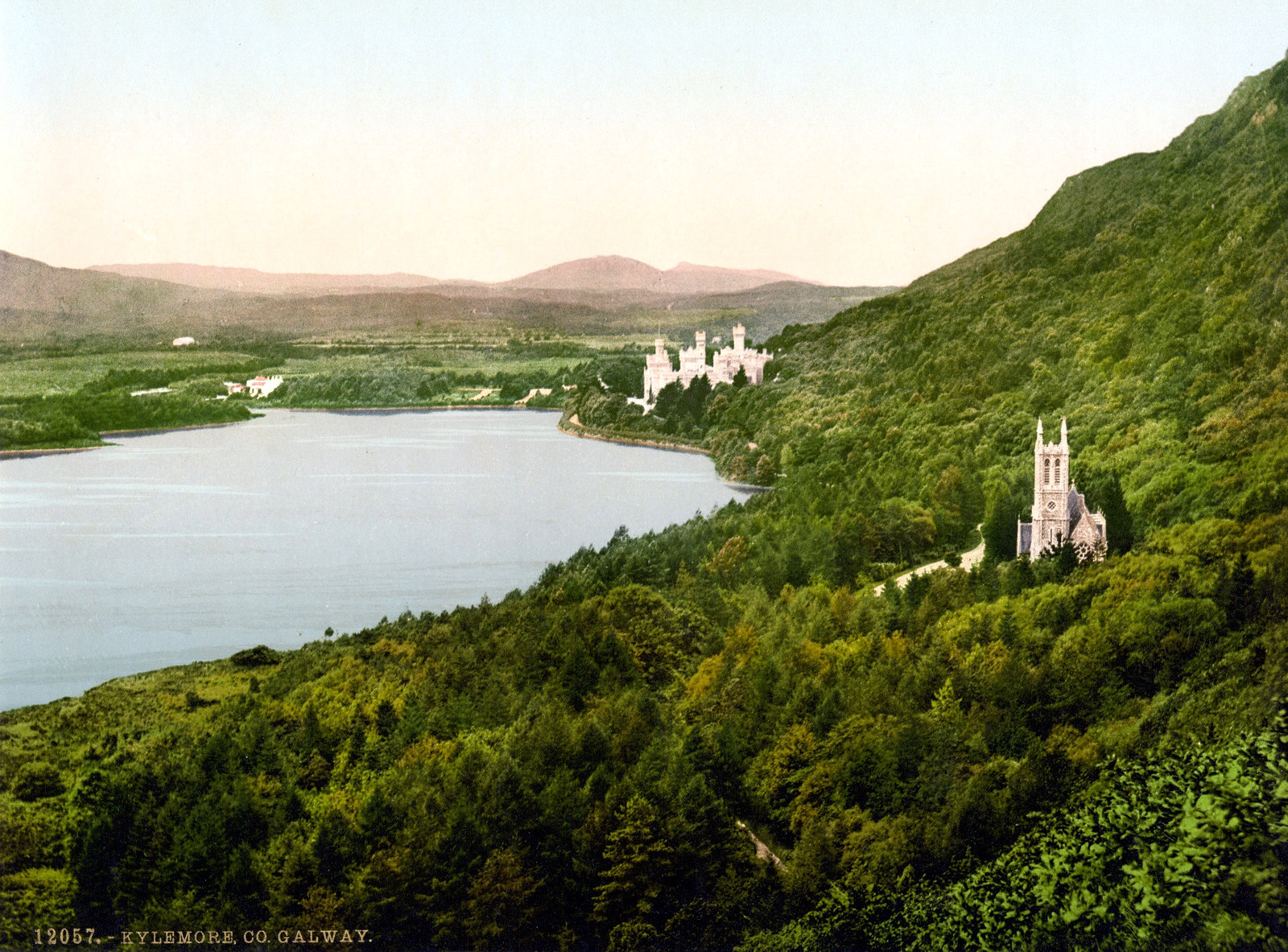

It had taken one hundred men four years to complete. But gazing across the lake at the castle’s reflection in the still waters, the couple knew it was worth the wait.

The fairytale dream

Their dream had been forged 16 years earlier when they honeymooned at this exact spot. Renting Kylemore Lodge, the Henrys had fallen in love with the bewitching beauty of the landscape.

Inheriting a sizeable fortune from his father, a wealthy cotton merchant from Manchester, England, no expense had been spared. Covering 40,000 square feet, with seventy rooms and made from granite shipped in by sea from Dalkey and limestone from Ballinasloe, it had cost £18,000 to build (about $3 million today).

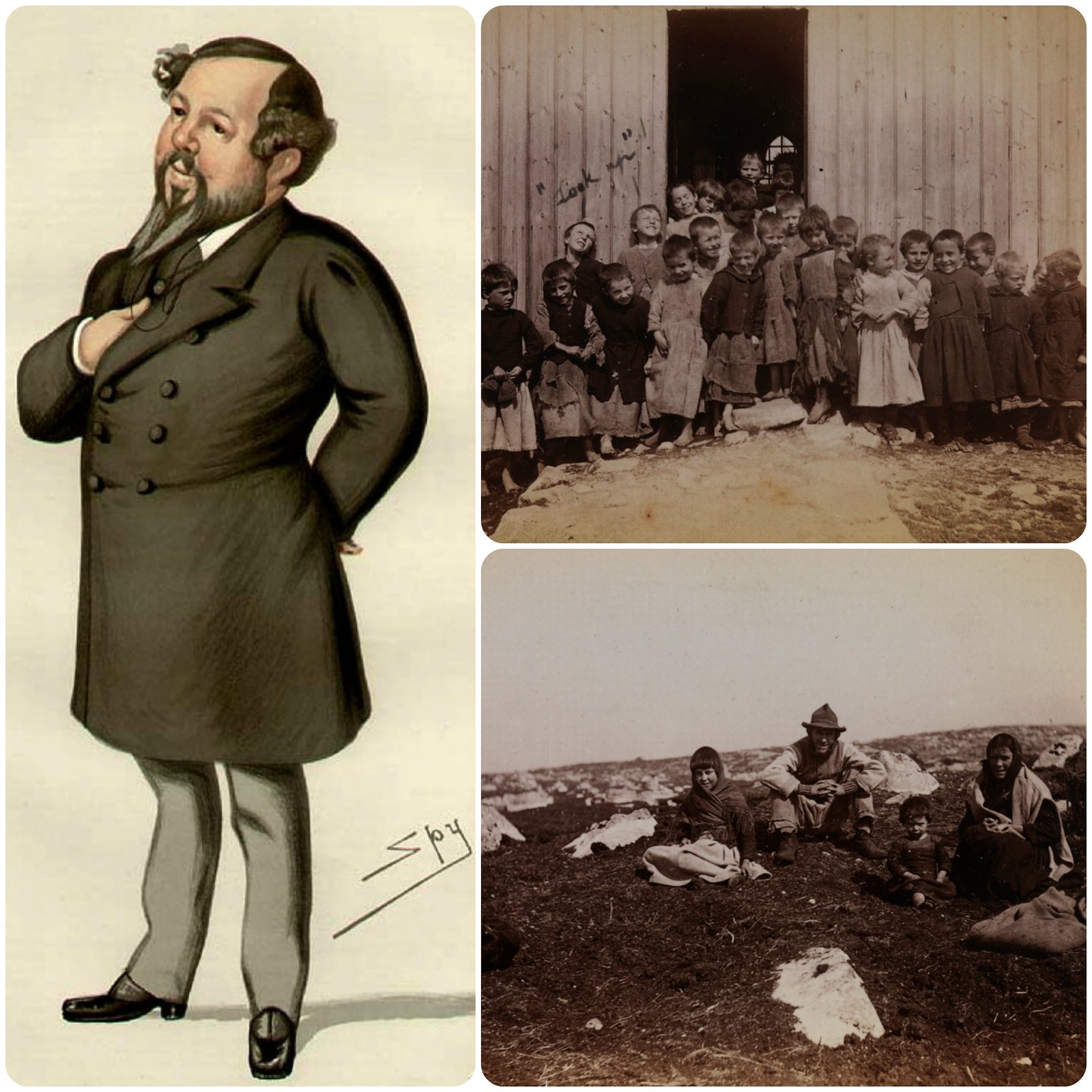

But Mitchell Henry’s dream was bigger than Kylemore Castle. He gave up his career as a medical doctor to take over the family business and entered politics as Member of Parliament for Galway County.

With much of Ireland still recovering from the Great Irish Famine of 1845-52, Henry wanted to help the local community by providing work, shelter and a school. He drained thousands of acres of waste marshland, turning it into the productive Kylemore Estate and providing material and social benefits to the entire region.

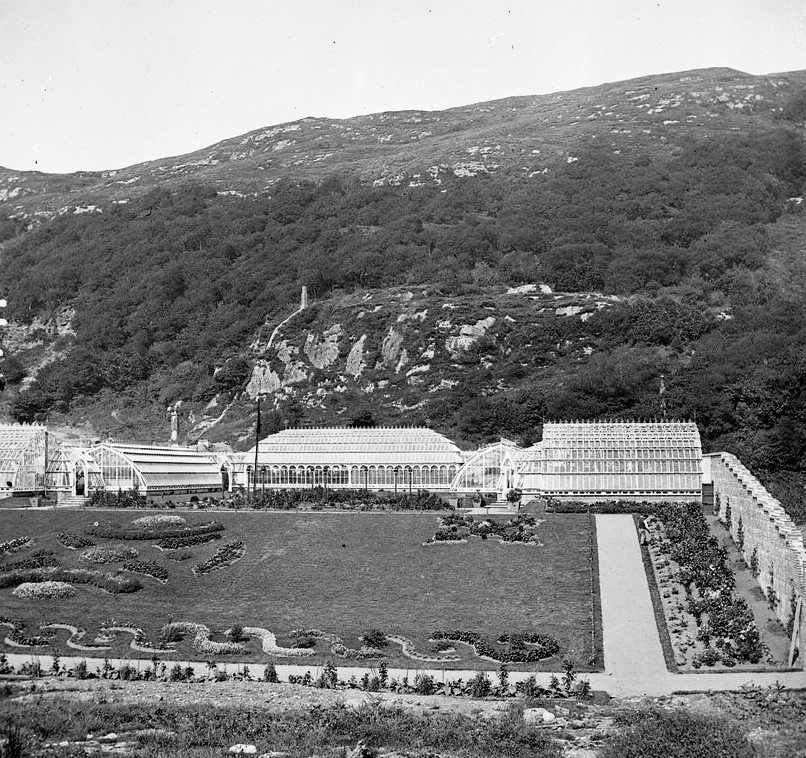

Victorian Walled Gardens

Included as part of the Kylemore Estate were large, walled Victorian Gardens, with 21 heated glass houses and a 60-foot banana house, growing exotic fruit and vegetables of all kinds.

Tragedy strikes

Just four short years later, Henry’s wife Margaret suddenly died from a fever contracted in Egypt.

Overwhelmed by grief, he built a beautiful memorial church on the shore of the lake about a mile from the castle, where Margaret was laid to rest and where he would eventually join her.

Built from Caen sandstone with internal columns of green Connemara marble, the church is a scaled-down replica of the neo-Gothic Bristol Cathedral.

The Duke and Duchess of Manchester

What does an English Duke do when he finally runs out of money and cannot repay his gambling debts? Why, he elopes with an American heiress and escapes to a castle on a lake in Ireland.

Such was the next chapter in the story of Kylemore.

In 1903, Mitchell Henry sold Kylemore to William Angus Drogo Montague, 9th Duke of Manchester. A notorious spendthrift, Manchester succeeded his father in the Dukedom at the age of fifteen.

His excessive spending and gambling drained the family fortune, but as luck would have it, he met Helena Zimmerman, daughter of Eugene Zimmerman, a railroad magnate and major stockholder in Standard Oil.

Much to the chagrin of the locals, the Duke and Duchess were far more concerned with lavishly entertaining guests than they were in managing the estate.

While the Duke was away in Europe and America, often as a paid guest of wealthy Americans like media mogul Randolph Hearst, the Duchess was seen speeding along country lanes in her Daimler motor car—quite the site in 1900s Connemara!

Some say the Duke lost Kylemore in a late night of gambling at the castle, but one thing for certain is that after Eugene Zimmerman died, the money to fund a life of partying dried up, and the Duke and Duchess were forced to sell.

A sanctuary from war-torn Europe

Kylemore Castle’s next owners were a group of Benedictine nuns from Belgium who had fled the horrors of World War One.

Before the war, the nun’s home town of Ypres, with its 20,000 inhabitants, engaged in nothing more than the peaceful pursuit of making Valenciennes lace.

Then the war arrived on their doorstep.

The ravages of the First World War turned one of Belgium’s most beautiful and historic cities into nothing more than a ghostly shell of its former glory.

Escaping the devastation of their beloved Ypres—their home base for three hundred and forty years—the nuns settled into Kylemore Castle in 1920 and converted it into the working Kylemore Abbey.

Restoring the Kylemore Abbey’s Victorian gardens and neo-gothic church have been major projects aided by donations and the work of local artisans.

Kylemore Abbey continues to be a self-sustaining working monastery and the Victorian gardens are open to the public.

Mitchell and Margaret Henry can rest at peace knowing their dream castle is in safe hands.

References

Wikipedia.org

KylemoreAbbey.com

Mitchell-Henry.co.uk