On August 1, 1714, Queen Anne of Great Britain drew her last breath, and the first of a series of Georges ascended to the throne, marking the dawn of an extraordinary new era of exploration, invention, industry, and art—the Georgian Era.

As the rural economy shifted to an urban industrial one, huge advances in science, design and engineering brought wealth to a new class of merchants, businessmen, and financiers.

This nouveau riche “middling sort”, or middle class, imitated the lifestyle of the aristocracy. Looking fashionable was a full-time occupation, and a tall order—since the Georgian aristocracy didn’t do things by halves.

Unlike the 17th century, it was parliament, not the monarchy, that held sway over governing the country.

Plush new town homes were built to house the politicians and their servants for the London season—corresponding to the sitting of parliament.

Fashion established the social pecking order. Aristocratic elites aped each other’s tastes, the middle class watched and learned, and the press fanned the public’s fascination with the glitterati.

This was the age of the Beau Monde.

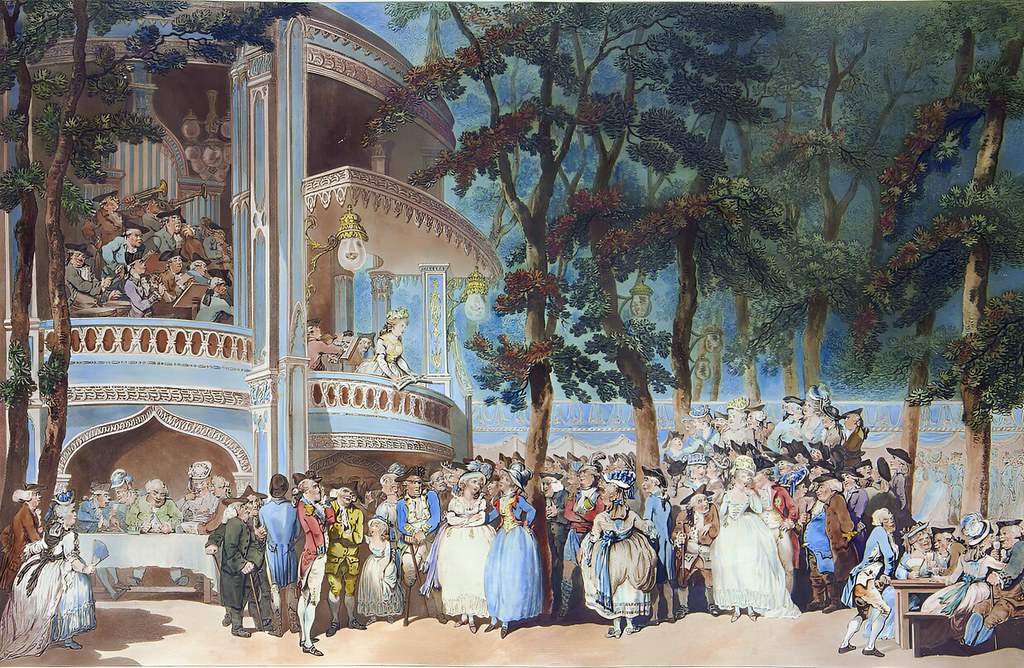

Pleasure gardens, exhibitions and assemblies were open to all who could afford tickets.

At Vauxhall Gardens, London, a shopkeeper’s wife and daughters could rub shoulders with the landed gentry.

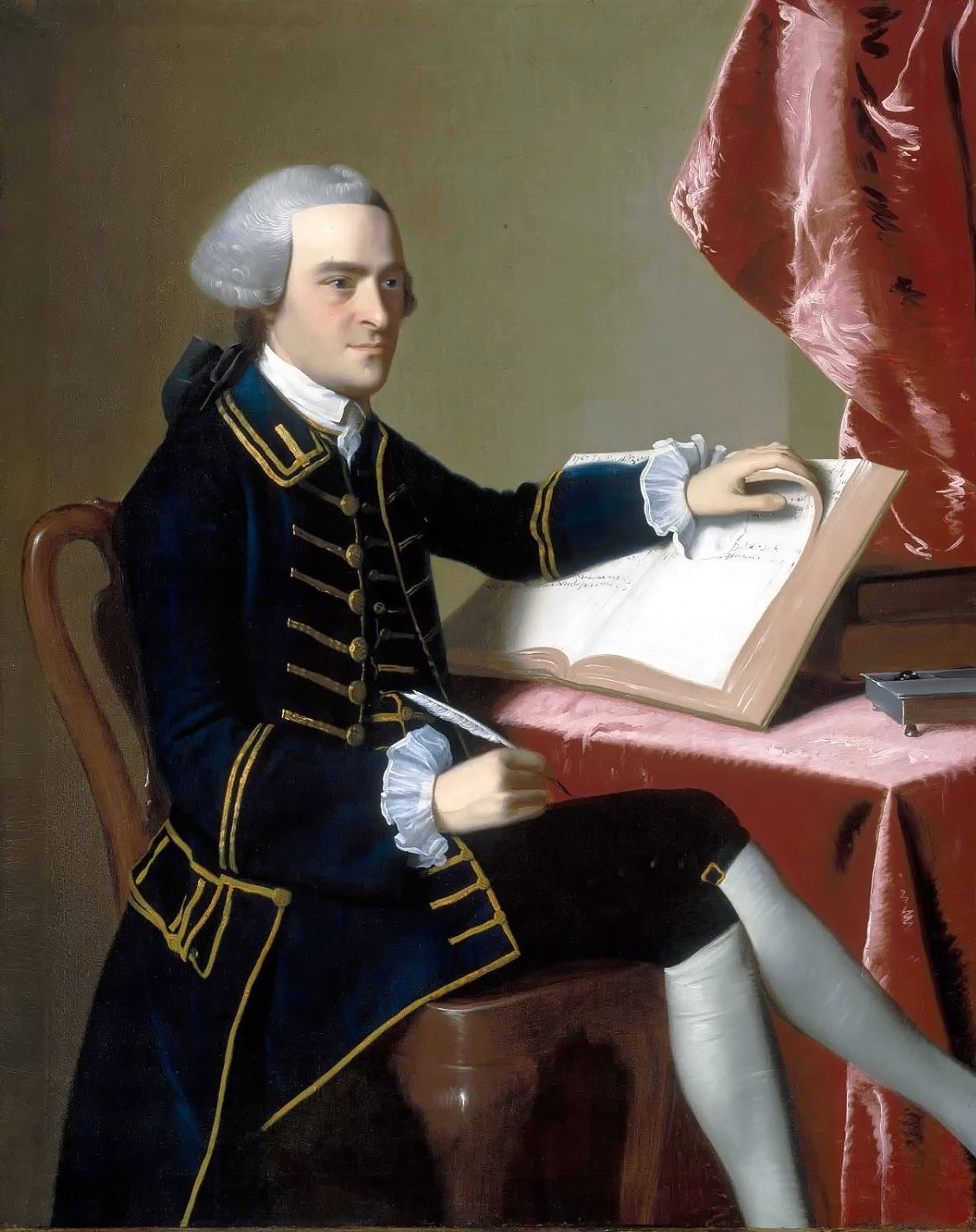

Men looked resplendent in their finery …

… a declaration of fashion on both sides of the Big Pond.

Men’s attire remained fairly static throughout the 18th century—predominantly coats, waistcoats and breeches—with stylistic changes to the fabric and cut.

Suits ranged from the elaborately embroidered silks and velvets of formal “full dress” to hard-wearing woolen garments more suitable for outdoor sport and country pursuits.

The 18th-century Beau Monde male wanted to look as fashionable as possible with seemingly little effort—exuding an air of “nonchalance.”

But it was women who really stole the show.

Between 1720 and 1780, ladies wore imposing Robes à la Française (French Dress) and Robes à l’Anglaise (English Dress).

Derived from the loose negligée sacque dress of the early part of the century, Robes à la Française had an open funnel-shaped front—often with stomacher panel—and wide rectangular skirts of expansive fabric decorated with delicate Rococo designs.

Obtaining such a silhouette took some hidden magic—an undergarment structure of panniers.

But, oh, what power the dress held over the male of the species …

The robe à la française compelled men everywhere to declare their love on bended knee.

Court etiquette demanded an altogether higher level of commitment to fashion. Size mattered. And one name stood out across Europe as synonymous with court fashion—Marie Antoinette.

You may be wondering, what’s the point? Well, the whole idea behind such width was to provide a panel where woven patterns, elaborate decorations and rich embroidery could be displayed and fully appreciated.

For the wearer of this little number, the only way to pass through doorways was literally sideways.

A variation on the Robe à la Française was the Robe à l’Anglaise, having a tight, fitted back, rather than the draped pleats of the Française.

Another popular style of gown in the 18th-century was the Robe à la Polonaise (Polish Dress).

Characterized by a close-fitting bodice and skirt gathered up into three separate puffed sections at the back, the polonaise was suspended by rows of little rings sewn inside the skirt, or sometimes ribbon ties forming decorative bows.

In the latter part of the 18th century, fashion became simpler and less elaborate. Spurred by modern Enlightenment thinking, the fashionability of Rococo went into decline.

Following the French Revolution, people began dressing for individual expression rather that social status.

In trendsetting France, out went the aristocracy and in came Napoleon’s first Empress, Joséphine de Beauharnais sporting the “Empire Silhouette”. High-waisted, with a long, flowing skirt, it was a look that would take Europe by storm.

The 18th-century Beau Monde was over … but the 19th century would see its own excesses.