The Grim Reaper made frequent visits to colonial Boston.

Disease and the difficulties of childbirth sent many men, women, and children to an early grave.

Seven smallpox epidemics had struck Boston by 1730.

The 1721 outbreak infected over half of Boston’s 11,000 population and left 850 dead.

Almost a quarter of Boston’s 17th-century grave markers are for children below the age of 10.

Losing a spouse to disease meant that remarriage was not only encouraged but was important to the survival of their families.

Headstone carving designs often symbolized the omnipresence of death.

Headstone Carving Symbols

Used since the medieval period as a symbol of mortality and reflecting the Puritan religious influence, the Winged Skull or Death’s Head is the most common headstone carving design in Boston’s oldest burying grounds.

Moving up on the cheerfulness scale is the much more genial Winged Face or Cherub.

Also called a “Soul Effigy“, it was a common headstone carving in the mid 1700s.

Popular after the American Revolution, the Urn-and-Willow symbolizes both death and mourning.

Urns are classical symbols of death because of their ancient use for holding ashes.

Weeping willows, as the name implies, symbolize sorrow at the loss of a loved one.

Wealthy Bostonians enthusiastically embraced Heraldic designs such as coats-of-arms which symbolized lineage and status.

The fruit around the edges symbolized eternal plenty.

Boston’s 17th-Century Burying Grounds

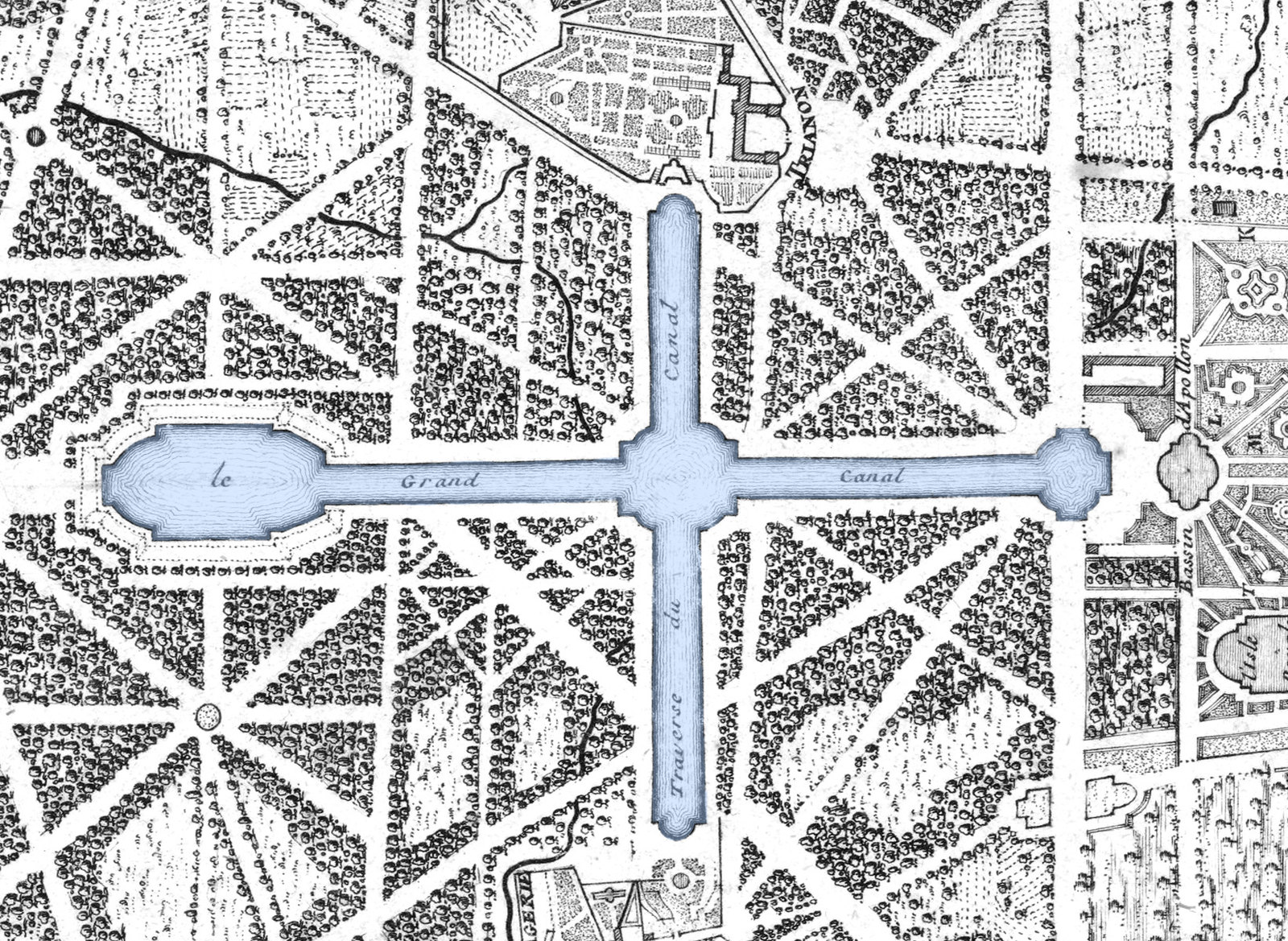

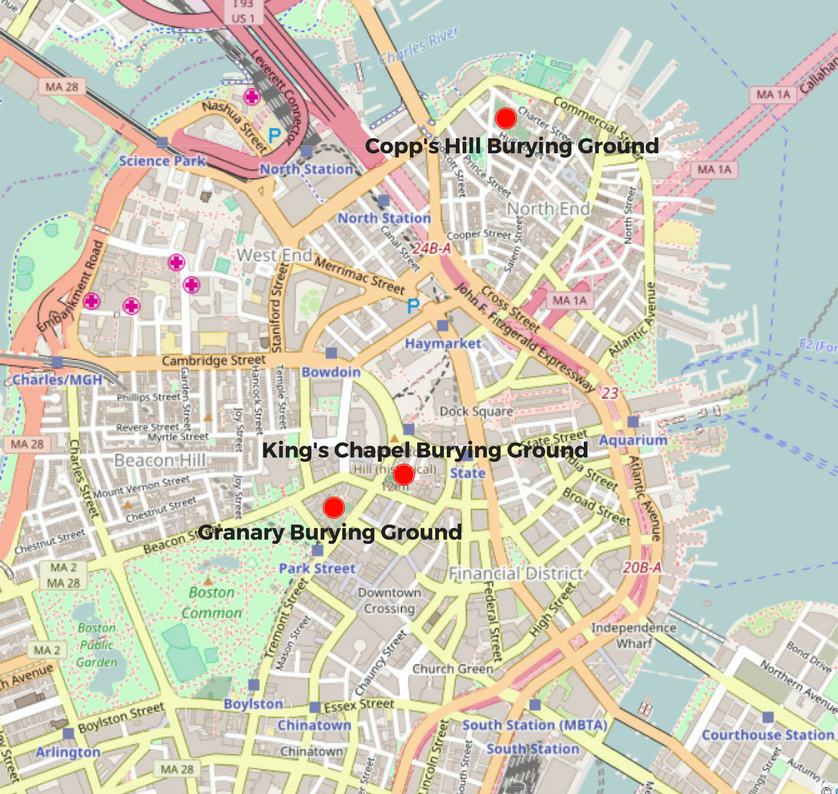

Within Boston’s three oldest burying grounds lie the remains of many of America’s pilgrims and Patriots of the American Revolution.

All three are on the Freedom Trail—a 2.5 mile path through downtown Boston passing 16 sites of historical significance.

King’s Chapel Burying Ground

Of Boston’s three 17th-century burying grounds, the oldest is King’s Chapel Burying Ground—simply called “the burying place” when it was first opened in 1630 on the outskirts of the new Puritan Settlement.

Seeking religious freedom and new economic opportunity in the “New World”, those buried here in the first 30 years were predominantly English-born immigrants.

Over 1,000 people are buried in the tiny space, but only 600 gravestones and 29 tabletop tombs remain.

Copp’s Hill Burying Ground

Established in 1659 and located in Boston’s North End, Copp’s Hill Burying Ground was the city’s second cemetery and was originally named “North Burying Ground”.

1200 marked graves include remains of notable Bostonians from the colonial era up to the 1850s.

Looking worse for wear, the gravestones protrude at odd angles, some leaning towards the water in Boston Inner Harbor, as if pulled by a giant magnet.

Ivy covers these old stones as Mother Nature tries to reclaim all traces of the dead.

But when even these stones finally return to nature, the stories of those they mark will live on in the hearts and minds of others.

Rank has its privileges, even in death.

And so it was for Cotton Mather, a Puritan minister, prolific author, and pamphleteer.

Mather played a prominent role in the case of the Irish Catholic washerwoman “Goody” Ann Glover, who was convicted of witchcraft and the last person to be hanged in Boston as a witch.

But it is his later involvement in the Salem witch trials for which Cotton Mather is best remembered.

After Ann Glover’s daughter was accused of stealing laundry by her employer Martha Goodwin’s own daughters, Ann found herself being accused of making the Goodwin children ill through witchcraft.

The majority of Boston’s population in the 1680s was Puritan and prejudiced against Catholics and foreigners.

Believing that the inability to say the Lord’s prayer in English was the mark of a witch, Goody Glover’s recital in Irish at her trial did not go down well with her accusers.

Whether Goody Glover chose not to speak English, or couldn’t speak it well enough is unclear, but either way she was sentenced to death on November 16, 1688, becoming the first Catholic martyr to be killed in Massachusetts.

300 years later, Boston City Council proclaimed November 16 as Goody Glover Day.

Legend has it that the holes in Daniel Malcolm’s gravestone (below) were made by British soldiers using it as target practice.

Captain Malcolm was a member of the Sons of Liberty opposed to the Townshend Acts which were passed by the British parliament to raise revenue in the colonies to pay the salaries of governors and judges and would eventually lead to the Boston Massacre of 1770.

Granary Burying Ground

Founded in 1660, Boston’s third-oldest cemetery is the final resting place for many notable revolutionary patriots.

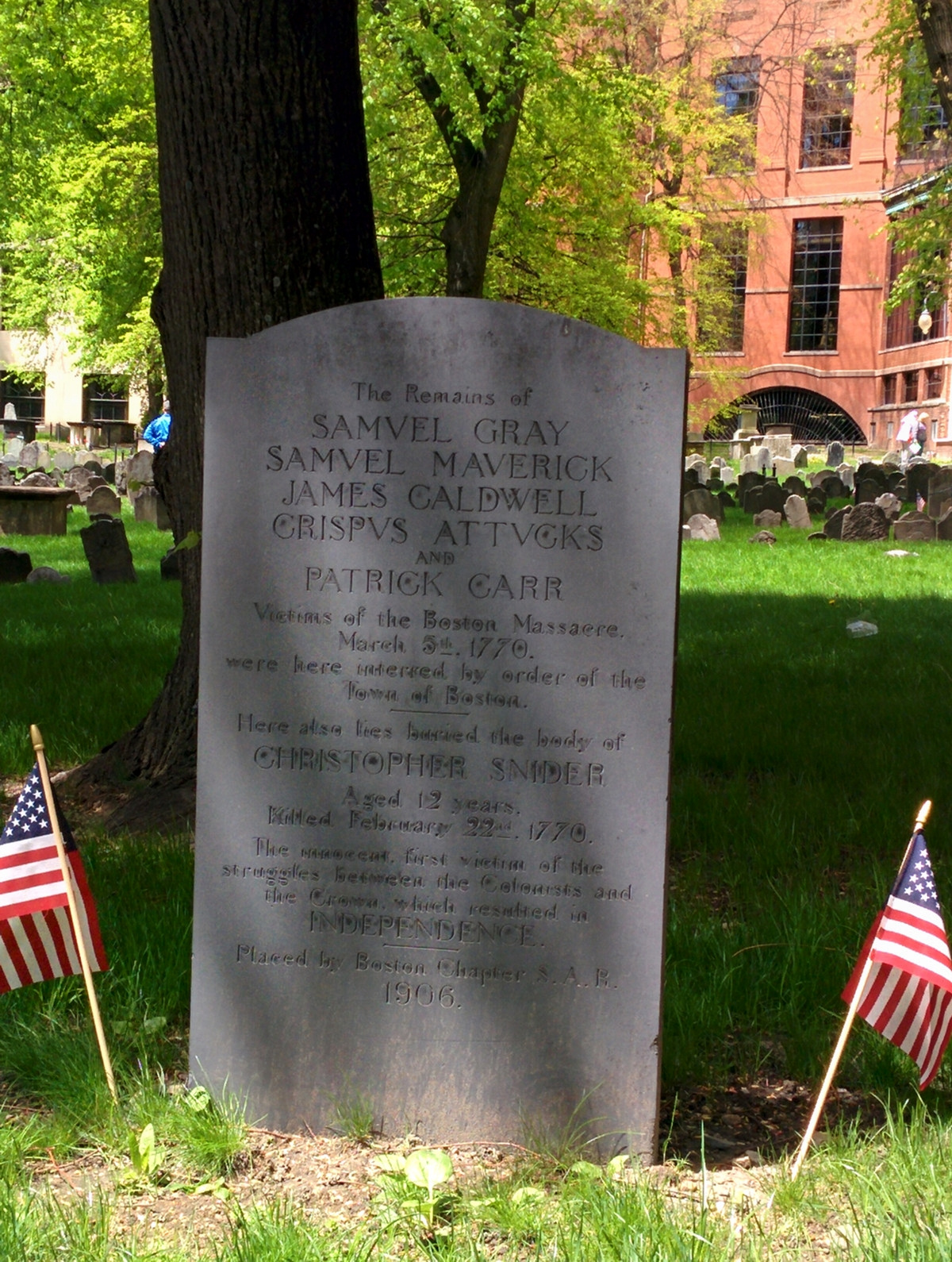

Buried here are Paul Revere, the five victims of the Boston Massacre, and three signers of the Declaration of Independence: Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and Robert Treat Paine.

The cemetery has 2,345 grave-markers, but historians estimate that as many as 5,000 people are buried here.

When you’re as revered as Paul Revere, you get a prominent memorial.

Paul Revere is best known for alerting the colonial militia to the approach of British forces before the battles of Lexington and Concord in the early stages of the Revolutionary War.

Paul Revere also created the famous engraving of the Boston Massacre of 1770 in which British soldiers shot and killed people while under attack by a mob.

Three people in the crowd of demonstrators were killed instantly and two died later—all are buried in the Granary Burying Ground.

Another Patriot of the Revolution resting in this peaceful place is the merchant and statesman John Hancock—a signer of the Declaration of Independence with one of the world’s most famous and stylish signatures.

As one of the colonies’ wealthiest men, Hancock used his money and influence to support the colonial cause.

Accused by the British of smuggling in 1768, his sloop Liberty was confiscated.

Although charges were later dropped, his ship was never returned—instead being refitted for service in the British Royal Navy.

Allegedly, Bostonians working for Hancock had locked a British customs official in the ship’s cabin to evade taxes while they unloaded a cargo of Madeira wine.

Samuel Adams was a statesman, philosopher and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States.

Resting in Granary Burying Ground, he was one of 12 children born in a time of high infant mortality. Only two of his siblings lived past their third birthday.

Adams’s 1768 Massachusetts Circular Letter calling for non-cooperation among colonial Patriots prompted the occupation of Boston by British soldiers and eventually resulted in the Boston Massacre of 1770, the Boston Tea Party of 1773, and the American Revolution of 1776.

There are many more tales from this fascinating period in America’s history.

Next time you’re in Boston, be sure to walk the Freedom Trail, stop to look at the 17th-century burying grounds, and marvel at the stories they hold.